At the Movies

The real Godfather: Peter Bart made Francis Ford Coppola an offer he couldn'trefuse

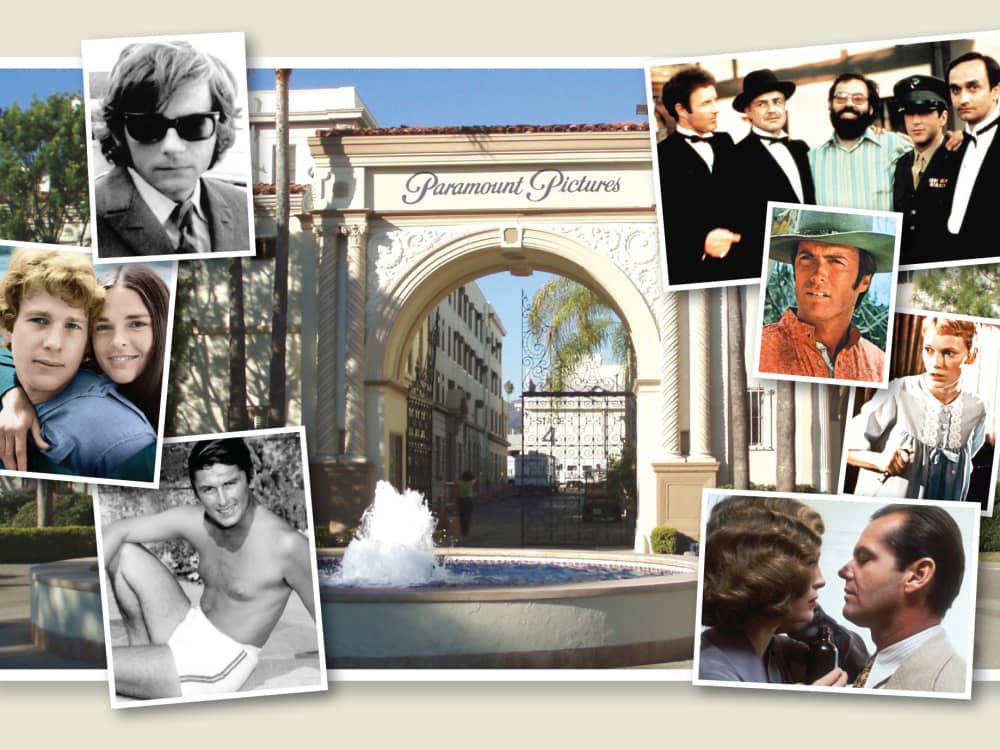

Hollywood's golden years are portrayed in "Infamous Players"

Hollywood's golden years are portrayed in "Infamous Players" Peter Bart

Peter Bart

When critics, academics and plain old movie buffs wax nostalgic for the New Hollywood era — a heyday that spanned, roughly speaking, from the release of Bonnie and Clyde (1967) to the disaster of Heaven’s Gate (1980) — they often tout the titles of movies produced during that golden age by Paramount Pictures.

And with good reason: Under the stewardship of Robert Evans, a failed actor improbably elevated to the job of production chief, and Peter Bart, a savvy New York Times journalist who signed on as Evans’ right-hand man, Paramount was responsible for an impressive percentage of the memorable films — including Chinatown, Rosemary’s Baby, Love Story, Harold and Maude, Medium Cool, Downhill Racer, Serpico, The Conversation, Paper Moon, Goodbye, Columbus and, of course, The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II — that have come to define that epochal era as a uniquely exciting and artistically innovative period for American cinema.

As Bart sees it, he and Evans were twice blessed: Fortunate to be in the right place at the right time, and nervy enough to take advantage of their good fortune. They came to Paramount after its purchase by the Austrian-born, American-based Charles Bluhdorn, a larger-than-life, richer-than-Croesus industrialist determined to make his mark in Hollywood.

“Charlie Bluhdorn bought Paramount in the first place because he really, uniquely, loved movies,” Bart says. “Unfortunately, he loved the wrong kinds of movies. He loved big musicals like Paint Your Wagon and Darling Lili,” two of several over-produced box office busts green-lighted by Bluhdorn before Evans and Bart came on board. “And what happened to Bob and I early on was, we realized that, while we admired his passion for film, Bluhdorn would kill us, he’d kill the studio, unless we got some of our own pictures going."

“And that’s basically what motivated us to become very aggressive about putting together some of these radically different movies. It was an adventurous time.”

Bart offers a vividly detailed and irresistibly entertaining account of his Paramount adventures in Infamous Players: A Tale of Movies, The Mob (and Sex), his newly published memoir, now on sale at fine bookstores everywhere. Given his strong ties to The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II — which will be screened on a double bill Sunday at the Alamo Draft House West Oaks — we decided to begin our conversation about his book by discussing the esteemed auteur of those two New Hollywood masterworks.

CultureMap: Right from the start, you wanted to sign Francis Ford Coppola to direct The Godfather, even though he was relatively unknown at the time, and hadn’t exactly set the world on fire with the films he’d already directed. What made you think he was the best guy for the job?

Peter Bart: To begin with, he’d written brilliant screenplays, like the one he did for Patton. And you figure that if someone is a brilliant writer and they’ve directed some pictures, even if they haven’t been hits, that’s something special. And if you just talk to Coppola, you’ll find that he comes across as a person with a really unique vision.

I’ve always resented the many, many stories that claim the only reason Paramount hired him was he was Italian and he was cheap. That’s what Francis himself tended to say, in a joking way, in interviews in years past: “Why did they hire me? Because I’m Italian, and I was cheap.”

That’s ridiculous. It’s true, the original intention was to make The Godfather as a relatively inexpensive movie. And it did cost $7 million. By today’s standards, I know, that’s incredible. But the real reason Francis won favor is he’s just a brilliant, brilliant guy. Is now, and was then.

CM: So why was there such resistance to him at first?

PB: Well, did you ever see Finian’s Rainbow?

CM: You mean the 1968 movie Coppola adapted from the ‘40s Broadway musical? Can’t say I ever have.

PB: That picture really didn’t work at all. And that was my biggest problem with getting Francis approved by people. That simply was the wrong material for him. And it was sort of a stilted show anyway. Oddly enough, I saw a revival of it on Broadway a few years ago, and I didn’t like it then. But at the time, people thought the movie was his fault.

CM: So how did you get him approved?

PB: Well, remember, when we first got him for the picture, no one was bothering me and Bob about it, because the book hadn’t been published yet. But when the book became a best-seller, everyone suddenly turned to me and said, “Wait a minute! What have you done? You’ve signed this unknown director who wants this burned-out actor in the lead role? That’s ridiculous!”

CM: That “burned-out actor” being Marlon Brando, correct?

PB: Correct. Finally, after we’d been gridlocked for months, I said to Evans, “Look, we only have one hope of getting Francis approved. Let’s just send him to see Charlie Bluhdorn. And he’ll persuade him in a minute, because he’s a brilliant talker.” And that’s exactly what happened. Charlie Bluhdorn met him, and then called us up and said in his thick Austrian accent, “This is a brilliant guy! Why haven’t we hired him to direct the fucking picture?” That’s what happened, basically.

CM: Even so, as you mention in Infamous Players, there was an attempt to get him replaced early in the production.

PB: That’s very true. I didn’t know about it at the time, but there was an editor named Aram Avakian, and he was part of a plot with Jack Ballard, who was the head of physical production, the guy who did the budgets, at Paramount. He was convinced from day one that Francis was incompetent, and in over his head. So he had set up Avakian as a back-up director. And at the right time, he was going to strike and get Francis kicked off the picture. And he almost succeeded.

Part of the problem was, in the first few weeks, Francis’ dailies looked too dark. And he was not keeping up with the schedule. You see, Francis had never really confided in anyone that he’d planned to shoot this picture with a whole different look. So when he and [cinematographer] Gordon Willis started shooting these scenes with Marlon, and they looked so dark, there was some panic on the part of people at the studio who were seeing dailies. And the thing is, I was Francis’ friend at the studio, to the degree that he had one, but he never called me up or tipped me off to say, “Look, for the next three or four days, I’m trying something different.” So I couldn’t intercede for him.

So I guess you could say that, to a certain degree, he was in over his head a bit. It was a big picture, and he didn’t have the street smarts that some directors have, politically, to curry the favor of the studio. Because when you’re shooting a picture, you do have to have allies in the front office. And he was ignorant of this. He was clumsy in terms of his personal relationships.

CM: Today, it’s not uncommon for a blockbuster like Transformers or Green Lantern to open on 3,000 or 4,000 screens. But back in 1972, wasn’t it unusual for an A-list movie like The Godfather to open on 400 screens?

PB: Yes, that was really the beginning of wider breaks for pictures. And Frank Yablans, who at the time was president of Paramount, was very clever to go so wide with that picture. Because by then, the book had become such a huge best-seller around the world. But the thing that always interested me about The Godfather is, the first time it was shown within the company, the marketing and distribution people were very skeptical about it. They felt there was not enough action, it was too talky – and it was too long.

CM: So you did an end run around the naysayers, right?

PB: At the time there was this ongoing war between the studio people and the marketing people. And that conflict was exacerbated by me, unfortunately, because I was so annoyed by them that I went out and hired some brilliant young ad guys to do campaigns outside of the studio. I sort of outsourced the advertising campaigns for a couple of other films, too, like Rosemary’s Baby and Goodbye, Columbus. That whole “Pray for Rosemary’s Baby” campaign was much too clever a campaign to be nurtured by a studio.

CM: Ironically, the smash success of The Godfather came along just a few months after the critical and box-office failure of Harold and Maude, a quirky comedy you had championed. But there was a happy ending: Harold and Maude went on to become an enduringly popular cult movie with a loyal following.

PB: That was quite a while afterwards, actually. At the time, it was very disappointing, because we had screened the picture a couple of times before it opened, and each time, the reactions were extraordinary. But then Frank Yablans decided to slip it into those Godfather dates that had opened up when Godfather was delayed from Christmas until March. There wasn’t time for a good advertising campaign. And let’s face it: Whatever else it was, Harold and Maude wasn’t a Christmas picture. So, really, to a degree, paradoxically, it was a victim of The Godfather.

It was a special picture. And certainly not a mass-market picture. But, again, what I love about it is it’s emblematic of the kinds of movies studios were making during that period. In that era, studios in general, and Paramount in particular, were making what would now be considered independent films. The whole point of view toward choosing what movies to make was so different.

It was a different era, to say the least. And I think one thing that made it different was we were really making pictures that we were looking forward to seeing. I had lunch with a couple of studio heads recently. And I asked each of them the question: “Are you, personally, looking forward to any of the pictures that you’re releasing this summer?” And in both cases, each of them looked bewildered, and said, “No. There may be some good pictures — but we’re not looking forward to seeing them.” So you could say it was a very selfish era back then. Evans and I really did look forward to seeing these pictures that we released.

CM: Do you think you could possibly get Harold and Maude made by a major studio today?

PB: It’s funny you ask. I showed Harold and Maude Sunday night out here in Los Angeles at an American Cinematheque screening. And I had with me onstage Cameron Crowe, who’s a big fan of [the late director] Hal Ashby. And it was a really fascinating screening, because the audience was pretty young, and I’d say about half of them had never seen the movie before. And the other half hadn’t seen it in about 20 or 30 years, by and large. And I was delighted, because not only was it a packed house, there was sustained applause after the picture. It’s really nice seeing that picture still being appreciated today.

But after the screening, someone in the audience asked, “If you were pitching that movie today, what cast would you suggest?” And I said, “Number one, I wouldn’t dare pitch this movie at a studio today. But, number two, if you had to, I guess you’d say… Justin Bieber and Betty White.”

(The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II will be screened back-to-back starting at 4 p.m. Sunday at the Alamo Draft House West Oaks. The films will be introduced by Houston film critic Regina Scruggs.)