The Review is In

Real magic: Houston Ballet and Trey McIntyre put the wonder back into Peter Pan

Fuzzy bunnies, padded booster seats, a stack of copies of Angelina Ballerina and a pirate hat: It's another night at Houston Ballet.

But not just any night. The ballet was abuzz for the opening performance of Trey McIntyre's stellar Peter Pan. Seats filled early and unsurprisingly children were many and the gift shop conspicuously overflowing with goods. One child dressed as a lost boy in a feathered hat toted a plastic dagger across the lobby during the first intermission.

Reader, I was wary. Don't hate me if I tell you I have a little Captain Hook in me. How many Swan Lakes have I seen dry up from the protests of girls and boys shifting uncomfortably because no matter how much they love dancing swans, tragic death-love-redemption is understandably just not their cup of tea?

As McIntyre shows so often, suggestion can be much more powerful than spectacle.

The power of McIntyre's Peter Pan is not only that it plays equally well to children and adults — without condescending to either. More importantly, it shows off the talents of a choreographer who knows how to capture and hold the attention of toddlers and smart-phone-addled adults.

How is this possible? Seamless elegance, a whip-fast pace, and sophisticated theatricality deployed with the lightest touch.

The curtain opens on one of many screens that populate Peter Pan. Strobe lights reveal momentary flashes of ballerinas and wavering spots of white, green and red light suggest fanciful faeries and boys with flashlights. As McIntyre shows so often, suggestion can be much more powerful than spectacle.

One of McIntyre's innovations in staging of this tale involves the parents. Simon Ball and Mireille Hassenboehler portray what are by no means throw-away roles. With their masks and marionette-like movement they suggest the adult world is imaginary while the world of childhood is the stuff of the real. Still, the children can't stop watching their parents dance, as if adults belonged to a club more special and secret than Peter Pan's lost boys.

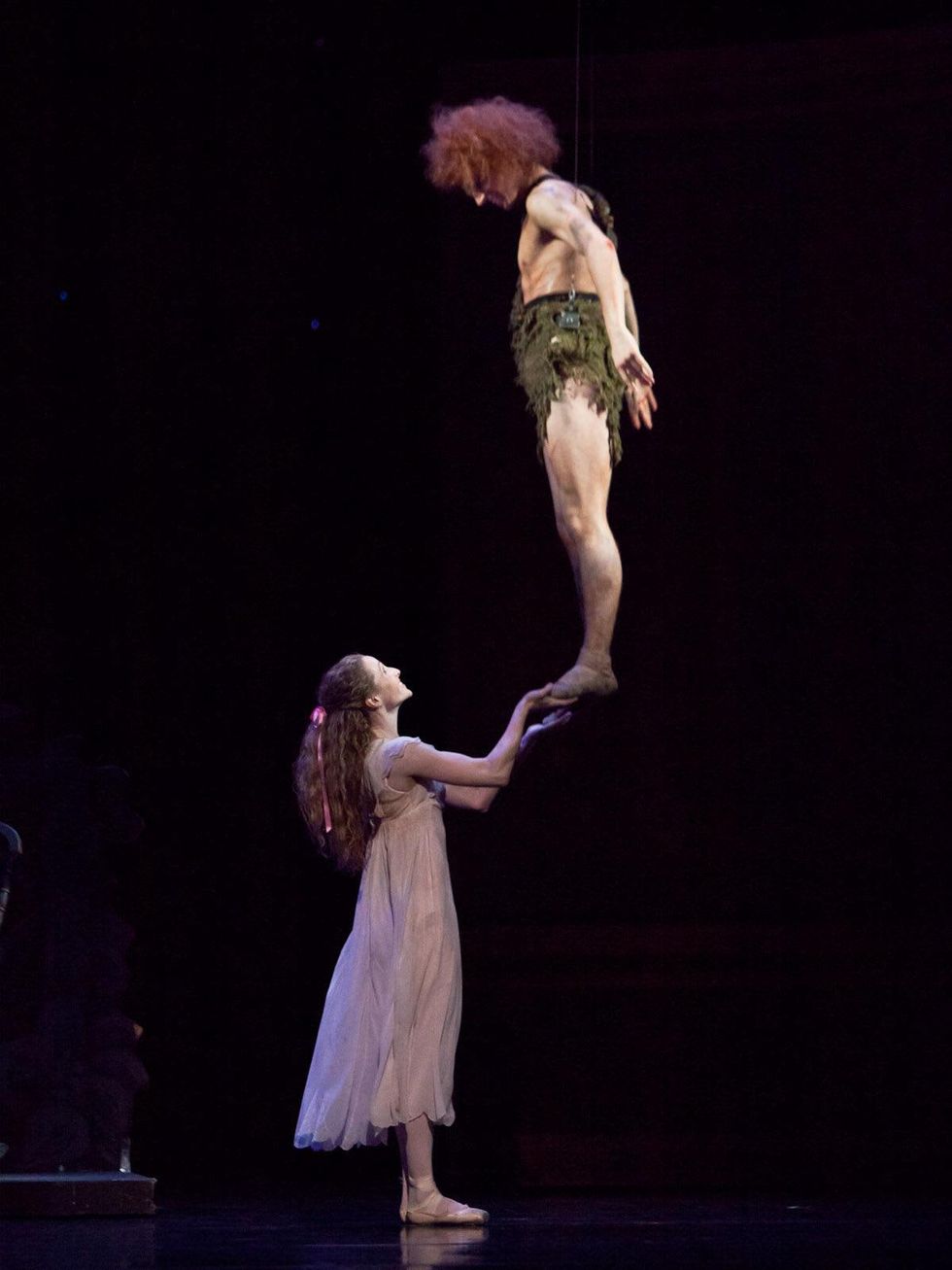

It's hard to imagine a better Wendy and Peter than Sara Webb and Joseph Walsh. The sweet precision of Webb and the swashbuckling panache of Walsh make an appropriately shy magnetism between these never-to-be lovers. In part it is their chemistry that makes wonder of moments that might descend into trickery.

For instance, flying. Who doesn't know this part of the story? Lesser artistry aims for the "tah-dah!" moment. McIntyre makes the moments of flight swift and effortless, as if it were natural for dancers to wheel into the sky.

Still, the children can't stop watching their parents dance, as if adults belonged to a club more special and secret than Peter Pan's lost boys.

Much of the magic of the first act comes from shadow and silhouette. But the set is clearly a co-star with the reddened caves of Neverland and the startling skeletal ship of the evil Captain Hook. The sets of Thomas Boyd, the lighting of Christina Giannelli, and the puppetry of Michael Curry and Warren Cochran deserve a standing ovation all their own.

The later acts highlight the deft group work of McIntyre's choreography. Take, for example, Merman and mermaids Conor Walsh, Nao Kusuzaki, Lauren Strongin, and Nozomi Iijima who danced a sweet and seductive pas de quatre. No wonder Captain Hook was keen to capture them.

The True Peter Pan Magic

Neverland is made of frames within frames. Screens, scrims and stages appear with ease and regularity. In the first act, a picture frame descends to capture the happy family. Wendy steps out, ready for adventure. Later Wendy sees, in dream, silhouettes on a screen growing larger and smaller and they rush by. We understand the tricks of light but the magic is no less compelling for knowing the trick.

In the second act, Captain Hook tries to win sympathy from Wendy with a fake home movie of his suffering as a mercilessly punished school boy, which explains his signature hook. But it's really a stage play with flickering light and features his own son dressed in black and white. He flings the curtains closed when Wendy, so moved by his suffering, nearly breaks the fourth wall.

A play within a film within a ballet? Stellar and smart.

We understand the tricks of light but the magic is no less compelling for knowing the trick.

Mermaids are saved, battles waged by a wonderful crew of dancing pirates, lost boys triumph and the villain is swallowed, hilariously, by a crocodile. A happy ending for most. But although Peter Pan is no tragedy, it ends with a bittersweet taste: the sadness of incompatibility.

Ball and Hassenboehler are beautifully inconsolable at the end, the father curled in the mother's lap as she rocks in a chair. But a happy reunion ensues. Still, Wendy and Peter Pan must dance their last pas de deux before his need for flight and her need for motherhood separate them forever.

But if nothing else there is, at the end of a night this bright, the sweetness of dream.