At the Art House

Who's Your Mommy? Examining a haunting adoption with Naomi Watts

Mother and Child will make you think about motherhood.

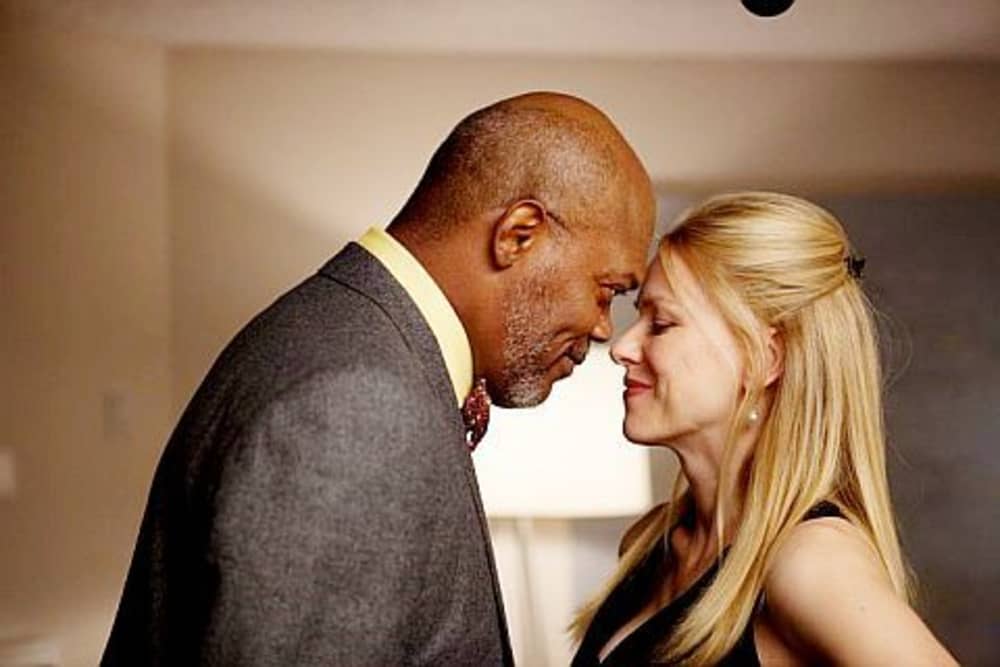

Mother and Child will make you think about motherhood. Samuel Jackson is surprisingly tender and Naomi Watts surprisingly evil inMother and Child.

Samuel Jackson is surprisingly tender and Naomi Watts surprisingly evil inMother and Child.

Why are there so few films about motherhood? After all, there are plenty of movies about being a dad. Even a movie titled Parenthood was really about the father. Is it from a general lack of respect for, or a lack of interest in, the enduring roles that women play? Maybe.

Or is it because motherhood is such an overwhelming, potentially all-encompassing role that the subject is hard to pin down to a specific story? I’m not talking about the relatively modern phenomenon of women trying to balance work and family. I’m talking about telling a story that takes on motherhood itself, the act of having given birth to a brand-new human being, and what that act means — to the mother.

This is the story that writer/director Rodrigo García tells in the new movie Mother and Child, though he approaches it by indirection and absence, a story about adoption, about not knowing who your mother is, or who your daughter is. And, though this question is not at the heart of the film, he also examines whether an adoptive mother is really a mother. (His answer is yes.)

Karen, a painfully brittle, and downright unpleasant physical therapist (played by a resolutely non-glamorous Annette Bening), gave up her daughter for adoption 37 years ago, when Karen was 14. This act has determined her entire life. Her bitterness, which is so extreme that in a lesser actor’s hands it might have been comical, in a Mommy Dearest way, is the result of her having spent virtually every waking minute wondering what became of her child.

Well, the viewer knows what happened to her. She, Elizabeth (Naomi Watts), became an ice queen of a lawyer, one of recent cinema’s more memorable bitches. When her pregnant neighbor directs a little too much corn-fed cheer her way, and projects a little too much happiness in her own pregnancy, Elizabeth takes a chilling revenge.

She seduces (if the overpowering technique that she displays here can truly be called ‘seductive’) the woman’s husband then leaves her panties in the wife’s drawer.

Becoming a mother herself is the last thing on Elizabeth’s mind. She got her tubes tied when she was 17, just to be sure.

Emotionally, the two women are frozen in place. Then the plot kicks in; Karen meets an improbably patient and caring man (Jimmy Smits) who coaxes her into the land of the living, while Elizabeth has a brief affair with her boss (a surprisingly tender Samuel L. Jackson). I won’t give away more of the plot, though I have to mention the film’s third subplot, the efforts by Lucy (Kerry Washington) to adopt.

She can’t have a child herself; her husband is ambivalent about adopting, and, when she meets the pregnant 20-year-old who’s auditioning potential mothers for her unwanted child, Lucy has to humiliate herself.

Some sentimentality does necessarily seep into the film; but it’s not a weeper. García’s vision may be reductive (do mothers who’ve given away their babies suffer as acutely into their 50s as Karen? Honestly, I don’t know). But he certainly takes the subject seriously, as perhaps only someone from a family-first, non-Anglo culture could do. (García is the son of Gabriel García Marquez, and he grew up in Colombia and Mexico.)

His film is bolstered tremendously by the performances of Bening and Watts, who make their rather one-note characters believable and compelling. The story does wobble near the end, once García starts introducing the likes of a superhumanly empathetic, blind teenaged girl who dispenses easy wisdom. And he’s heavy-handed with his irony, which I suppose he would simply call ‘fate.’

(The film was produced by Alejandro González Iñárritu, director of Babel and Amores Perros, and it shares the sometimes grinding fatalism of those films.)

But it doesn’t collapse. The ending is in fact quite moving.

Babies is also showing at the Angelika. It would make for an interesting double-feature with Mother and Child. Maybe we could throw in Sex and the City 2 and make a day of it.