Lunatic Fringe

The transformative power of the automobile: From Dali to Yellow Cab to the ArtCar Parade

Hot Rod Mary art carPhoto by Chris Becker

Hot Rod Mary art carPhoto by Chris Becker "Taxi, New York Night"Photo by Ted Croner

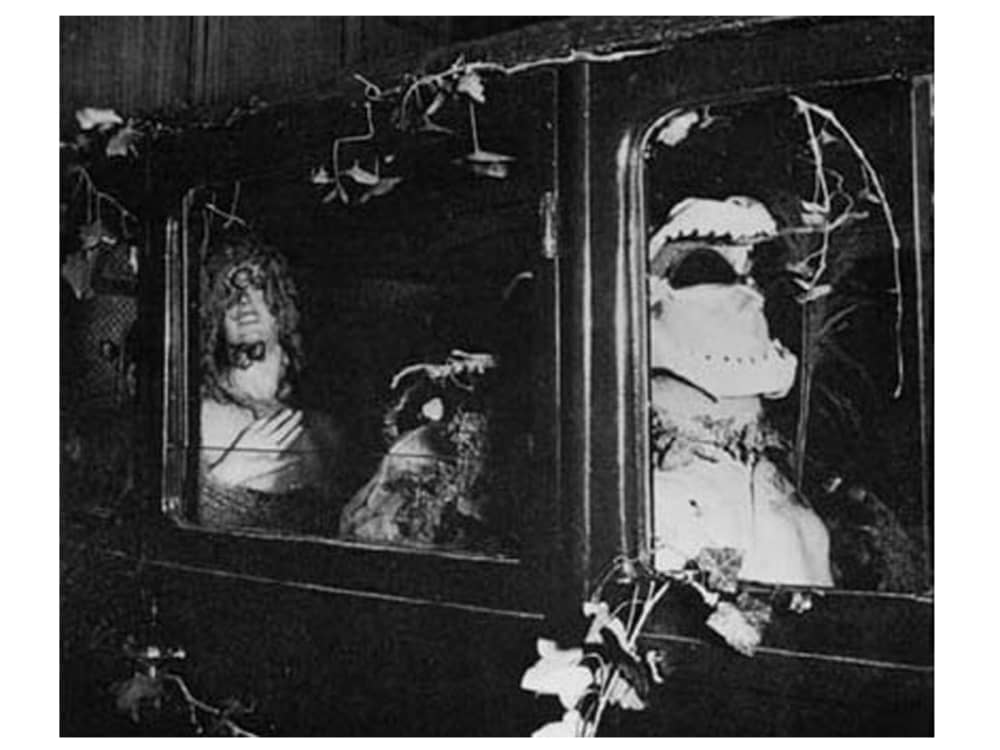

"Taxi, New York Night"Photo by Ted Croner Salvador Dali, "Rainy Taxi," 1938, aka Mannequin Rotting in a Taxi Cab

Salvador Dali, "Rainy Taxi," 1938, aka Mannequin Rotting in a Taxi Cab

In 1938, at the dawn of the Second World War, 60 artists from 14 nations — each allied with the hugely influential movement known as Surrealism — presented The International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

For this show, artist Salvador Dali contributed Raining Taxi, aka Mannequin rotting in a taxi-cab — a taxi with rain falling within its interior and a blonde female mannequin in the back seat, her plastic skin covered in lettuce and snails.

If Dali’s car somehow magically appeared in this weekend’s Art Car Parade, would it really surprise anyone along the parade route? I doubt anyone would think “Hmm…how’d that Surrealist creation get in our parade?” Even if Dali were somehow behind the wheel — with that mustache? He’d fit right in.

In her essay “Happenings: An art of radical juxtaposition,” literary theorist Susan Sontag quotes the French poet Comte de Lautréamont to describe “a mode of sensibility” that appears in contemporary art, literature and film known popularly as “surrealism,” but famously branded by Lautréamont as “the fortuitous encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.”

That sensibility is especially evident in the Art Car Parade, although not every participating automobile could be called surreal. There are definitely some variants to the “art car” theme.

A few ways the convoy’s vehicles are transformed:

- Car is transformed into a traveling billboard advertisement for a useless product or young start-up. (Yawn…)

- Car is an earnest community project, with its usually young participants riding in their completed vehicle, shyly waving to the passing crowd.

- Car displays details for participating in a political or socially conscious cause. (Legalize it!)

- Car is an incomplete version of some variant of the three above bullets, and its drivers are — or are on their way to getting — thoroughly wasted.

- Car is transmogrified into a completely surreal sculpture, a “trompe l’oeil brought to life," an unholy amalgamation of machine and a “happening” on wheels, often covered with hundreds of small tactile objects.

I should mention that I haven’t driven in more than 20 years. Yes, it’s true. And I’ll wait as you clean up the coffee you just spit all over your computer screen.

The last time I drove was…well, the last time I drove legally was actually in Houston many, many years ago. After relocating here from New York City, I quickly realized how much I had relied on the scumbag robber barons that run the Big Apple’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

The New York City subways rarely ran consistently or even offered a mildly pleasant ride. The subway commute is a trip you endure, rather than enjoy, hence the tacit agreement of near silence as you stand shoulder to shoulder with your fellow “strap hangers,” all with earbuds in your ears. The only sound, other than the occasional screech of the subway wheels, is the orifice-muted, microscopic, wimpy codec of mp3s.

Sometimes, the trains just didn’t show up. In that situation, you had to flag a cab:

Ted Croner's 1947 Taxi, New York at Night…

What an incredible photo. This isn’t even a cab; it's a piece of abstract art. But someone was inside that cab when Croner took this photo. And I assume someone was behind the wheel. Like Dali’s dazed mannequin enjoying a rain shower as snails ooze over her attractive shoulders, are we, too, somehow transformed when we get inside the metal chassis of an automobile? Whether behind the wheel or in the passenger seat, do we become a work of art?

“One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art,” said Oscar Wilde.

“…or drive a work of art!” (Addendum by Culturemap columnist Chris Becker.)

So, coming out of Houston's Avant Garden one evening last summer, my friend, and for that night, my ride home, somehow remained calm and collected as it dawned on us that his car had been towed by the city of Houston.

This realization didn’t come until after several minutes of our wandering the dark streets of Montrose, pressing that button on my friend’s keychain that makes your car go “Chirp! I’m here!” Hey, I didn’t see a sign, and neither had he. Come on, Houston! Parking in this city is insanely complicated.

Eventually, in order to get back home, I ended up in a Yellow Cab. The driver, who seemed a little nervous, had the radio tuned to an FM station but turned down really, really low, which was fine by me. I was tired, irritated and wanted to keep an eye on that meter, you know what I’m saying?

The tradition of mutual distrust that exists between cab driver and passenger in the big city is ingrained within me, and I sometimes forget that most people I meet in Houston, including cab drivers, are actually pretty cool.

The cab’s transmission was so shot that I could hear the bottom of the cab dragging on the street, slowing the speed of the ride. Not exactly Ted Croner's taxi at night. But again, I was really fried at that point, and I didn’t care. Man, what was UP with this town? When was I gonna get around to getting my driver’s license? And did I even WANT to drive in Houston?

Then, coming from the cab’s radio, I heard a strangely familiar, eerie synthesized whistle…a minor third up, followed by a falling fourth and a drone straight out of classic Pink Floyd. Hey, I know this song!

“This is a cool song…” I muttered. My driver, relieved now that the ice was finally broken, agreed excitedly: “Oh, man. I LOVE this song,” and cranked that shit up just in time for the slow slide down the electric guitar strings before the drums and bass kick in, and the lead singer half screams, half snarls:

“LUNATIC FRINGE!!!! (…fringe…fringe…fringe…) / WE ALL KNOW YOU’RE OUT THERE!!! / YOU’RE IN HIDING / BUT YOU WON’T GET TOO FAR!!!”

The cab driver and I banged our heads in time to the song for the rest of the ride home. Awesome.

Eventually, I’m going to have to get that driver’s license and join the ranks of my fellow Houstonians, many of whom, as a result of transformative experiences inside cars, spend time and money to transform their modes of transportation into something symbiotic with a modern city. As Sontag writes, “…the brutal disharmony of buildings in size and style, the wild juxtaposition of store signs.”

Recently, while riding in a rental car driven by a friend of mine who was visiting from New York, I tried in vain to guide us out of downtown Houston to the Museum District. My friend, who was being very patient, even though we were completely mixed up, said to me at one point: “This city…it’s just weird! But do you know what I mean?”

Yep.