Priceless Treasure

After 2,500-year journey, first known human rights declaration finds temporary home at MFAH

For all its historical importance, the renowned Cyrus Cylinder is a surprisingly understated artifact — a baguette-size piece of clay inscribed with a straight-forward proclamation from Cyrus the Great, the founding ruler of the first Persian Empire.

But within its faded cuneiform script lies what many believe to be the earliest recorded example of human rights. Thanks to a rare traveling exhibition organized by the British Museum, Houstonians will get a change to see the storied document firsthand.

Created in 532 BCE upon Cyrus' defeat of the notorious Babylonian Empire, the clay decree orders an end to forced labor and calls for a return to religious tolerance. Although specific groups are not mentioned, Judeo-Christian scholars have long viewed the cylinder as evidence of the ruler's campaign to construct the Second Jewish Temple, the first of which was demolished when the Jewish population was exiled from Jerusalem a half century earlier.

Curtis says the object likely served to commemorate the conquest rather than to usher in a bold new social order.

"When the cylinder was found by archeologist Hormuzd Rassamin in 1879, Cyrus the Great was already very well known and highly-regarded in the Old Testament," John Curtis of the British Museum, which sponsored the object's original 19th-century excavation, tells CultureMap. "It was translated very quickly and people soon realized the cylinder actually corroborated many ancient texts."

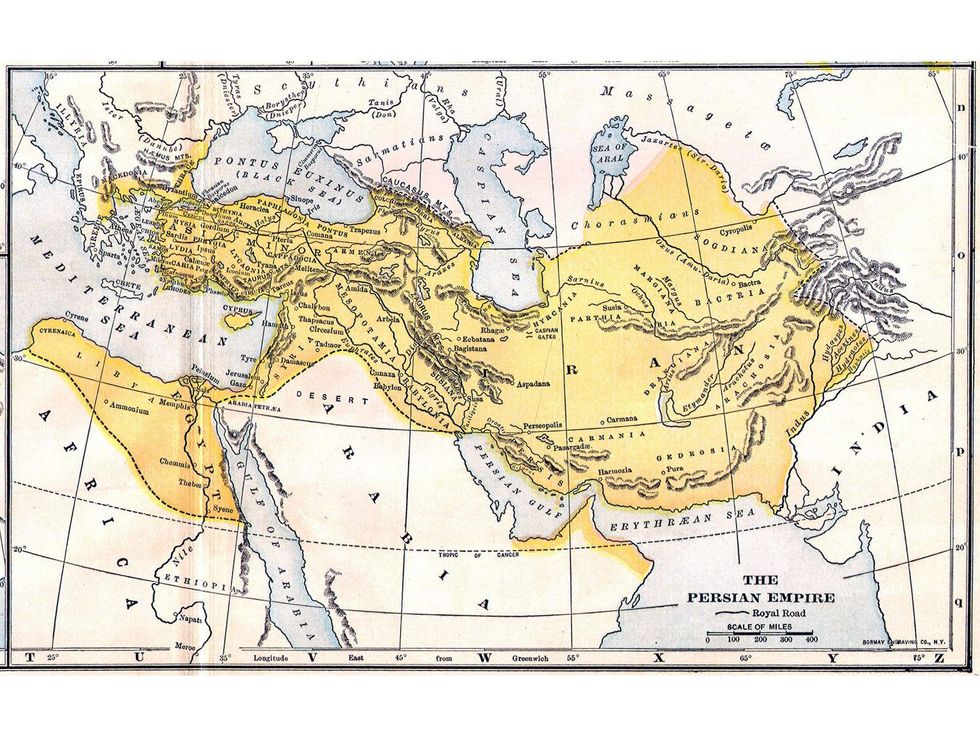

Recent research suggests that the proclamation on the cylinder, which was located inside the wall of a building reconstructed after Cyrus' defeat of Babylon, was reproduced largely word-for-word throughout an empire that stretched from modern-day Turkey to India. Curtis says the object likely served to commemorate the conquest rather than to usher in a bold new social order.

"While it's sometimes called the first human rights declaration, concepts like that didn't really exist in antiquity," Curtis says. "But there's little doubt that he's allowing, if not actually promoting, freedom of worship and religion in the text. He's permitting the return of those deported by Nebuchadnezzar, including the Jewish people to Jerusalem."

As it grew to include Egypt during the next two centuries, the Persian Empire would become the cultural heartbeat of the ancient world. Its writings, art and political style — a number of which are on display with the Cyrus Cylinder — would capture the imagination of Alexander the Great, who seized control of the empire in 330 BCE.

The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia: A New Beginning is on view through June 14 on the first floor of the MFAH Law Building. Visit the museum website for further information.