Mondo Cinema

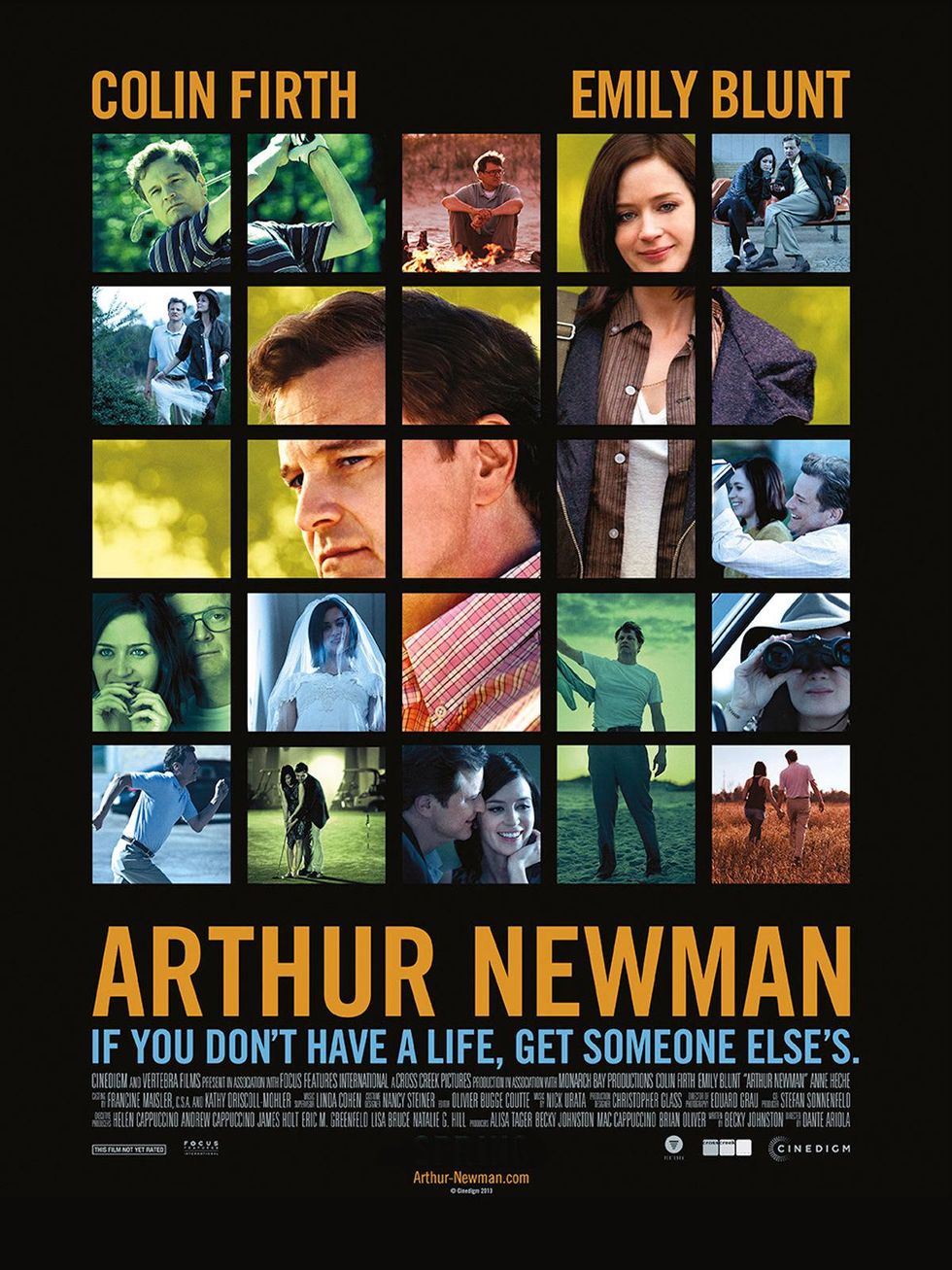

Indie movies: Colin Firth takes on a new identity, French sperm donor meets his match, John Cusack's CIA adventure

How far do you have go to get from where – and who – you are? Hard to say. But in the world according to Arthur Newman (at the AMC Studio 30 and Gulf Pointe 30 theaters) — a subtle and insinuating indie drama by first-time feature filmmaker Dante Ariola — even going to extremes may not be far enough.

Much of the movie’s unassumingly idiosyncratic appeal can be attributed to Colin Firth’s arrestingly low-key lead performance in the title role.

Actually, to be more precise, Firth plays Wallace Avery, a glumly discontent middle-aged fellow who flamed out quickly years ago during his brief run on the PGA circuit, and, when we first meet him, is unhappily employed as a floor manager at a FedEx site in Orlando. Wallace in turns plays Arthur Newman, an identity he assumes to claim a casually offered job as a resident golf pro at a county club in Terre Haute, Indiana.

And the role playing doesn’t end there.

Before he leaves Orlando, Wallace fakes his own death in a haphazard, half-thought-out fashion that indicates (a) Wallace has little experience in breaking the rules and/or acting on impulse, and (b) he believes, and not without good reason, that no one – not even his bored girlfriend (Anne Heche) or his estranged 13-year-old son (Lucas Hedges) – will spend much time investigating his disappearance, or mourning his passing.

Emily Blunt is excellent as Mike, often coming across as a darker, more dangerous version of the similarly unstable character played to Oscar-winning perfection by Jennifer Lawrence in Silver Linings Playbook.

Wallace is, as the bored girlfriend reluctantly admits and Wallace himself doesn't bother to deny, a singularly boring individual. And it's a credit to Firth that he actually plays Wallace as a singularly boring individual, because, on some level, Wallace knows he's something far short of Mr. Excitement. Which makes it all the more plausible that he'd do something, anything, everything to turn himself into somebody else.

But even after he hits the road, bound for greener pastures, Wallace/Arthur – who I’ll henceforth refer to simply as Arthur – can’t quite escape his true self. Deep down, he’s an instinctively decent, even kind-hearted person, which explains why he’s the only one in a crowd of bystanders to attempt CPR on a stranger suffering a seizure. (His efforts are for naught, alas, but never mind: Scriptwriter Becky Johnston shrewdly plants the incident for a third-act pay-off.)

It also explains why Arthur comes to the aid of Michaela “Mike” Fitzgerald (Emily Blunt), a troubled young woman he finds passed out near a motel swimming pool after she imbibes too much morphine-laced cough syrup.

Turns out that Mike, too, is playing a role: Her real name is Charlotte, and she’s traveling with the I.D. of her twin sister, a recently institutionalized paranoid schizophrenic. She’s going nowhere and everywhere fast, in the vague hope that she will somehow escape, or at least temporarily outrace, what she fears, based on a family history of mental instability, is her unavoidable future.

The morning after Arthur rushes Mike to an ER, he strolls into her hospital room with a typically cheery greeting: “Don’t you look as sharp as a tack!” Her fuzzy-headed response: “Did I have sex with you?” She seems surprised that she did no such thing. He seems embarrassed that she’d ask such a question.

Emily Blunt is excellent as Mike, often coming across as a darker, more dangerous version of the similarly unstable character played to Oscar-winning perfection by Jennifer Lawrence in Silver Linings Playbook. And the most excellent thing about her excellent performance is the genuine suspense it generates. For long stretches of Arthur Newman, you don’t know what Mike will do next, or why she’ll do it. Only gradually do you realize that, hey, Mike doesn’t know, either.

Despite her initial lack of focus, however, it doesn’t take long for Mike to see through Arthur’s fake identity, and to demand that he take her along for the ride to Terre Haute. And that in turn leads to a cross-country journey that often resembles a ‘70s-style road movie, with occasional detours into sharply observed psychological drama and eccentrically sexy romantic comedy.

During their travels, Mike and Arthur do indeed become lovers – kinda-sorta – and engage in close encounters of the mildly kinky kind: At Mike's urging, they break into other people’s homes, pretend to be those people, and engage in the sort of uninhibited sex that seems, for each of them, quite literally out of character.

That’s the upside of their adventure. The downside: Here and there, the movie indicates Mike is a textbook example of a manic depressive. (Even more problematic: She’s a kleptomaniac.) And if you find yourself, right from the start, thinking Arthur is pretty naïve to assume it will be so easy to start a new life in Terre Haute – let’s just say that Arthur not only hasn’t thought of everything, he hasn’t even fully considered the basics.

Dante Ariola first made his mark (and won several awards) as a director of TV commercials, a job that traditionally calls for the ability to convey information with vivid imagery at warp speed. But there is nothing unduly hurried or self-consciously stylized about this, his first feature, a purposefully muted yet gently amusing and always involving movie that respects its characters and their complexities too much to goose the pacing along with flash and filigree. (And if that sounds like it may be too slow for you – well, maybe not, and certainly not for me.)

On the other hand, Ariola does reveal a sharp eye for revealing details that emphasize and underscore the underlying themes of Becky Johnston’s script. Note, for example, that in this tale of assumed identities, almost everything happens in places without distinguishing characteristics. Indeed, every hotel or motel room, inexpensive or otherwise, is so drearily anonymous, it’s almost as though Mike and Arthur keep winding up in the same place again and again.

Things don’t begin to improve for them until they risk a change in direction.

Other screens, other cinema

Two openings of note this weekend at the Sundance Cinemas: Starbuck, a French-Canadian comedy, inspired by real-life events, about a slackerish fortysomething whose past as a prolific sperm donor comes back to haunt him; and Lore, an acclaimed German drama starring Saskia Rosendahl as a 14-year-old girl who must fend for her siblings after their SS officer father and Nazi-sympathizing mother surrender to Allied forces at the end of World War II.

Over at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, animator Chris Sullivan will be on hand to introduce the H-Town premiere of Consuming Spirits, his darkly melancholy overview of desperate lives in a rustbelt town. The screening is set for 7 p.m. Saturday at MFAH.

Meanwhile, at the AMC Studio 30, John Cusack is a CIA assassin who thinks he’s been taken out of the line of fire – yeah, right! – when he is reassigned to The Numbers Station, a secluded installation where an eager young cryptologist (Malin Akerman) broadcasts coded messages to agents in the field. Unfortunately, that installation is not quite secluded enough to avoid being invaded by bad people with worse plans.