Cultural treasure hunt

More than salsa: Concert series sets the record straight on Houston's Latino community

Salsa music isn't any more Latin than Taco Bells' Gorditas or Chalupas. Salsa is as Latin as Coca-Cola is American, meaning, they embrace traces of their respective lifeways without being an accurate representative of their true zeitgeist.

And to think otherwise is just jejune.

Pat Jasper, director of the Folklife and Traditional Arts Program at Houston Arts Alliance, is out to set the record straight about one of Houston's fastest growing demographic sectors.

"¡Uno, Dos, Tres!: The Many Musics of Houston's Latino Community," presented in cahoots with Multicultural Education and Counseling through the Arts (MECA), Talento Bilingüe de Houston and KPFT 90.1 FM, is a series of three concerts that probe into three emerging Houston communities. The initiative kicks off with El Rectorado del Son on Saturday (5 p.m., at Talento Bilingüe), continues with Son Vallenato on April 13 at MECA and concludes with Lumalali and guests on May 18 at Fifth Ward Jam.

Each of the locations have been carefully chosen because of their connection to the performing groups. With the help of the Folklife and Traditional Arts Program's newest addition, program associate Angel Quesada, each performance also includes a workshop that fosters further connection between the audience, musicians and the genre.

"Dress for the occasion and come prepared to dance," Jasper explains. "I can't imagine anyone sitting through these type of rhythms."

Cultural treasure hunts

Houston trades on and is proud of being proclaimed the single most diverse city in the U.S., she says. A big part of that is the Latino community. But as large as it is, much of it, beyond the lore of the Mexican-American population, is invisible to those who aren't a part of its daily activities. The only method to uncover these practices includes knocking on doors, asking questions and following the cultural yellow brick road.

"Dominant cultures need to pay attention to these communities to reinforce the positive return of their cultural investment on the whole city."

"Most people who hold keys to their respective communities work day jobs, sometimes in construction and labor," she says. "You have to submit to the process and venture into these communities at night and on the weekends."

That's how Jasper came to learn about the philosophies of the Garifuna community, whose Central American roots bloomed from a melange of West Africa, the Arawaks, who are indigenous people of the West Indies, and the Caribs, who are American-Indians from the northern coastal lands of South America. Many of the Garifuna, whose music was inscribed to UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008, resettled in Houston from New Orleans post Hurricane Katrina.

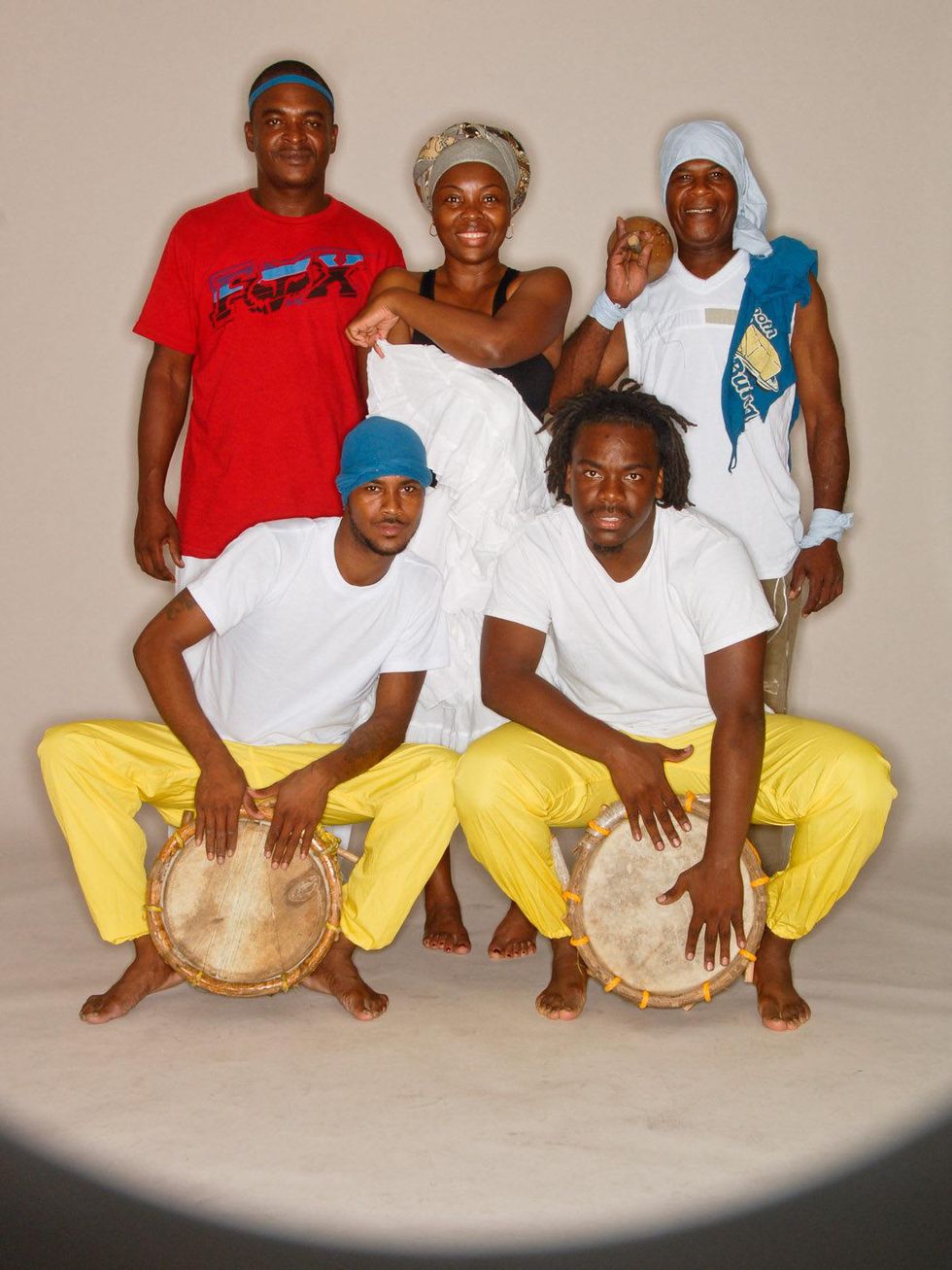

Jasper decided to attend services at the Iglesia Garifuna Misericordia de Dios in Frenchtown, a two-story yellow building with big balconies — what one would expect from a small, Pentecostal style house of worship typical of coastal Central American towns. She sat through bible study lessons led half in Spanish and half in Garifuna. She befriended community leaders and stumbled upon Lumalali, meaning "the voice," a quintet of Garifuna musicians led by Honduran percussionist Fernando Mejia. The group meets regularly in public parks to share their gifts.

Garifuna music inherits the driving rhythms of West Africa.

"The Garifuna get absorbed in the barrios of the black community where they disappear," Jasper says. "Dominant cultures need to pay attention to these communities to reinforce the positive return of their cultural investment on the whole city — a productive scenario of co-dependence."

Folklorists understand that tradition is a form of local knowledge that's passed down from one generation to another, she adds. Customs about music, food, dance, how to build a home, construction styles, quilting and textiles — proven strategies for survival and self-sufficiency — are embedded as intelligence. The lyrics of songs, for example, serve as repositories of heritage and identity in communities that do not have official, recorded histories. Songs are a medium that communicate news or retains a story that will continue to be a lesson.

"These immigrant communities offer a great cultural gift to everyone."

It's much more than salsa

Although most listeners will be readily familiar with cumbia as the national folk music of Colombia, Vallenato, which emerged from the country's northeastern Valley of Upar, is as popular, such that it was added as a category in the Latin Grammy Awards in 2006.

Son Vallenato regularly performs at flea markets, "pulgas," where the eight-member band morphs al fresco areas into street dance parties. The group's leader, Victor Velasquez, learned to play the accordion by ear and carries many of these one-man-band aerophones to his gigs. The difference between Vallenato and Tejano conjunto lies in how the accordion's reeds are tuned.

To recruit Cuban group El Rectorado del Son, which focuses on son bolero, chachachá and son montuno with bongos, bass, guitar and trumpet, conversations were held while the musicians took cigarette breaks between sets during regular Friday night engagements at Mi Pueblito Restaurant on Richmond.

"Don't tell these guys you like Salsa music," Jasper jokes. "They will talk an earful about how this type of Latin rock and roll dilutes the essence of Cuban music. These musicians are in love with son, and their passion is evident when they play."

What Jasper hopes ensues from "¡Uno, Dos, Tres!" is some larger, grassroots, field work effort to unearth who's out there, what traditions are thriving in Houston and how they journeyed here.

"We are just scratching the surface here," she says. "These immigrant communities offer a great cultural gift to everyone."