Tattered Jeans

The Ant Man from the Louisiana marsh: Meet my Chinese hero

Xuan Chen emerges from the marsh.Photo by Katie Oxford

Xuan Chen emerges from the marsh.Photo by Katie Oxford Xuan Chen, loading netsPhoto by Katie Oxford

Xuan Chen, loading netsPhoto by Katie Oxford He doesn't believe in bug spray.Photo by Katie Oxford

He doesn't believe in bug spray.Photo by Katie Oxford Field study: the marshPhoto by Katie Oxford

Field study: the marshPhoto by Katie Oxford Xuan Chen in the marsh, deep left, looking as small as a beePhoto by Katie Oxford

Xuan Chen in the marsh, deep left, looking as small as a beePhoto by Katie Oxford Xuan Chen casts a net in the marsh.Photo by Katie Oxford

Xuan Chen casts a net in the marsh.Photo by Katie Oxford Outside McDonald's where we sat down.Photo by Katie Oxford

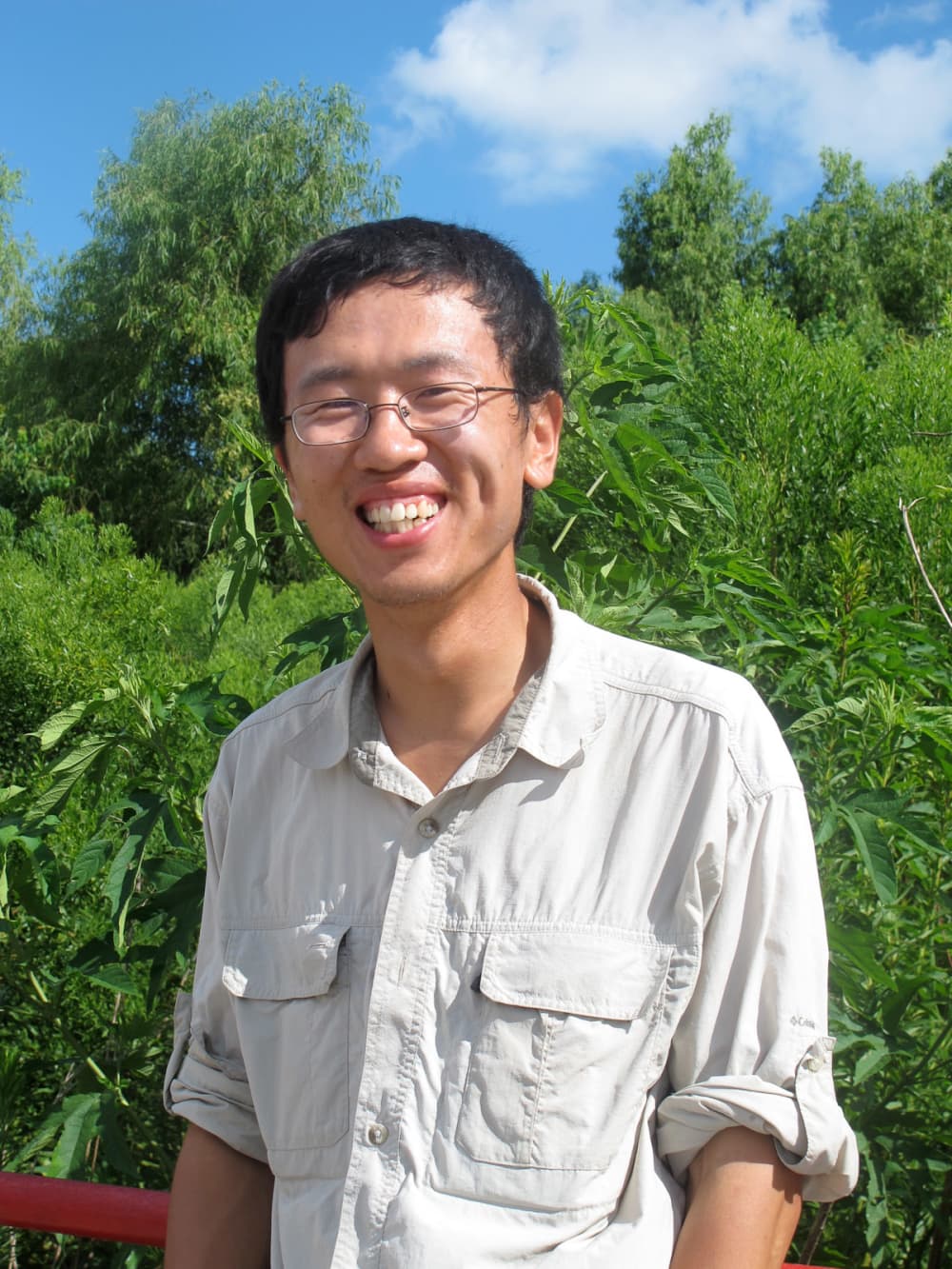

Outside McDonald's where we sat down.Photo by Katie Oxford My heroPhoto by Katie Oxford

My heroPhoto by Katie Oxford

Editor's note: Katie Oxford is on the ground and in the boats in Louisiana, reporting from the heart of the Gulf oil spill disaster. This is her eighth column from the scene.

Have you ever watched a heron in the marsh?

It moves in slow motion, literally, making steps without the slightest bob of the head. Its neck stretches forward as though sliding over glass and then seemingly waits there for the rest of the body to follow. It can disappear into the marsh like a sunset and, from an entirely different place, rise again as softly.

I thought of a heron while watching Xuan Chen. At the time, I had no idea who or what was in the marsh, only that when I spotted something, I had to find out like a hound dog has to hunt. I pulled onto the shoulder of Louisiana Highway 1 and parked the car.

Huge trucks on their way to Port Fourchon roared past, rocking my convertible, not practical in these parts. Some trucks came so close that at one point I considered moving on. But the hound dog still called. I could not take my eyes off the marsh, so vast that it looked like if you walked out far enough, you’d drop off the edge of the earth.

For an hour, I watched with amazement as a person moved and disappeared into the marsh just like the heron. Occasionally, the person reappeared, casting something outward as though seining for fish.

Finally, a man emerged from the marsh, carrying a large container; fine netting and wearing the same outfit my brothers wore when duck hunting. He also wore a smile. The kind you might see on someone stepping from the ocean, refreshed.

I wondered how in the world in this 110 heat index, his skin hadn’t melted off his bones and filled his rubber waders. He was still smiling even when I fired my camera in his face without so much as a hello first or asking if I could.

After he reached his vehicle (also parked on the shoulder) and removed his waders, I introduced myself. His name was Xuan Chen. We stood on the highway hollering over the trucks zooming past.

“I study ant diversity in the marsh!” Xuan answered. “How many species and how many individuals!” He’d started walking at 9 a..m. that morning. It was now almost three o’clock, the heat feeling like a 300-degree oven.

“Hey Xuan!” I hollered, “Could we go somewhere and talk?”

“Yes,” he nodded, pointing back toward Golden Meadow where I’d started. “McDonald’s?”

The sitdown

Twenty minutes later we were in air conditioning. Xuan had ordered ice cream and was standing at the table waiting for me when I approached.

“I’m dark for a Chinese,” he offered. “It’s the sun.”

We then sat across from one another and began a two-hour visit that would feel like minutes. I was utterly enthralled.

In the marsh, Xuan Chen is poetry in motion. Out of the marsh, I realized, he’s just pure poetry. In or out, this 26-year-old boy from Beijing is, in my book, a hero.

Xuan knew at age 15 what he wanted to do. He loved flowers, animals; his favorites are tigers and lions. He attended China Agriculture University in Beijing and received a master’s degree in entomology (a keen interest in bees especially).

He wanted to study more, particularly ants, so he came to the United States to earn a PhD in ecology at LSU.

“Why here?” I asked him, and his answer came reverently. “In all the world, there’s no marsh like this one.”

Xuan went on to explain that few study ants in the marsh. Not surprising considering the hardships involved in the field study. One especially. Xuan doesn’t wear repellent! Nada. As we visited I saw an ant on his collar that, stupidly, I felt compelled to point out.

“Oh, it’s OK,” he smiled, never budging.

“My field is not very big, just a small part,” Xuan explained. I asked him why it was important to study ants. “Because ants are a good indicator,” he answered. “If we know how many ants are in the marsh, we MAY know how many insects will STAY in the marsh. Birds and other animals eat insects so the ants are the foundation of the food chain or we call it ‘food web.’ Birds are easier because they’re big and easy to watch … people like birds.”

Xuan drew me a picture. A circle for a marsh. He likened the marsh to a “kidney,” the forest, “the lung of the earth.”

“Not only the marsh but all kinds of wetlands are the kidneys of landscape because they stabilize water supply, cleanse polluted waters and protect shorelines and so on.” He explained that in Louisiana there are four kinds of marsh — saline, brackish, intermediate (salt and fresh water combined) and fresh water, his favorite.

“More kinds of ants here,” he pointed. “In the salt marsh, some ants can survive, but not many."

He brought up “disturbance ecology.” That is, how people disturb the environment i.e. building, etc. “Fire ants can survive in disturbance environment,” he stated. Makes sense I thought. You’d have to be fierce to survive humans.

I asked Xuan if I could go into the field with him and it was the only time he looked somber.

“I can’t let you go. It’s terrible. The heat, the mosquitoes. Others students have asked if they could go too but I don’t let anyone go with me.” I understood and admired him even more for his focus and commitment.

When I thanked Xuan for his time, for teaching me, for the work he was doing, he looked happy again.

“As an ecologist, I have a responsibility to explain to people the importance of ecology,” he said, smiling sweetly.

Xuan’s dream is to someday work for the World Wildlife Foundation. I’ve no doubt his dream will come true. He’d given me inspiration and a restored faith in an innocence that I’d thought was disappearing as rapidly as the fresh water marsh he loves.

“Your parents must be so proud of you Xuan,” I said. He looked embarrassed.

“My father is an entomologist too,” he said, smiling. “A very good one.”

Xuan Chen is making his Papa, and the planet, very proud.

Other articles in this series:

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook