Learn Something

Not just Cinco de Drinko: The real story behind Cinco de Mayo

Cinco de Mayo commemorates the Mexican army's unlikely victory over Frenchforces at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, under the leadership of MexicanGeneral Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín.

Cinco de Mayo commemorates the Mexican army's unlikely victory over Frenchforces at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, under the leadership of MexicanGeneral Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín. Dancers in colorful costumes are traditional sights at Cinco de Mayocelebrations.

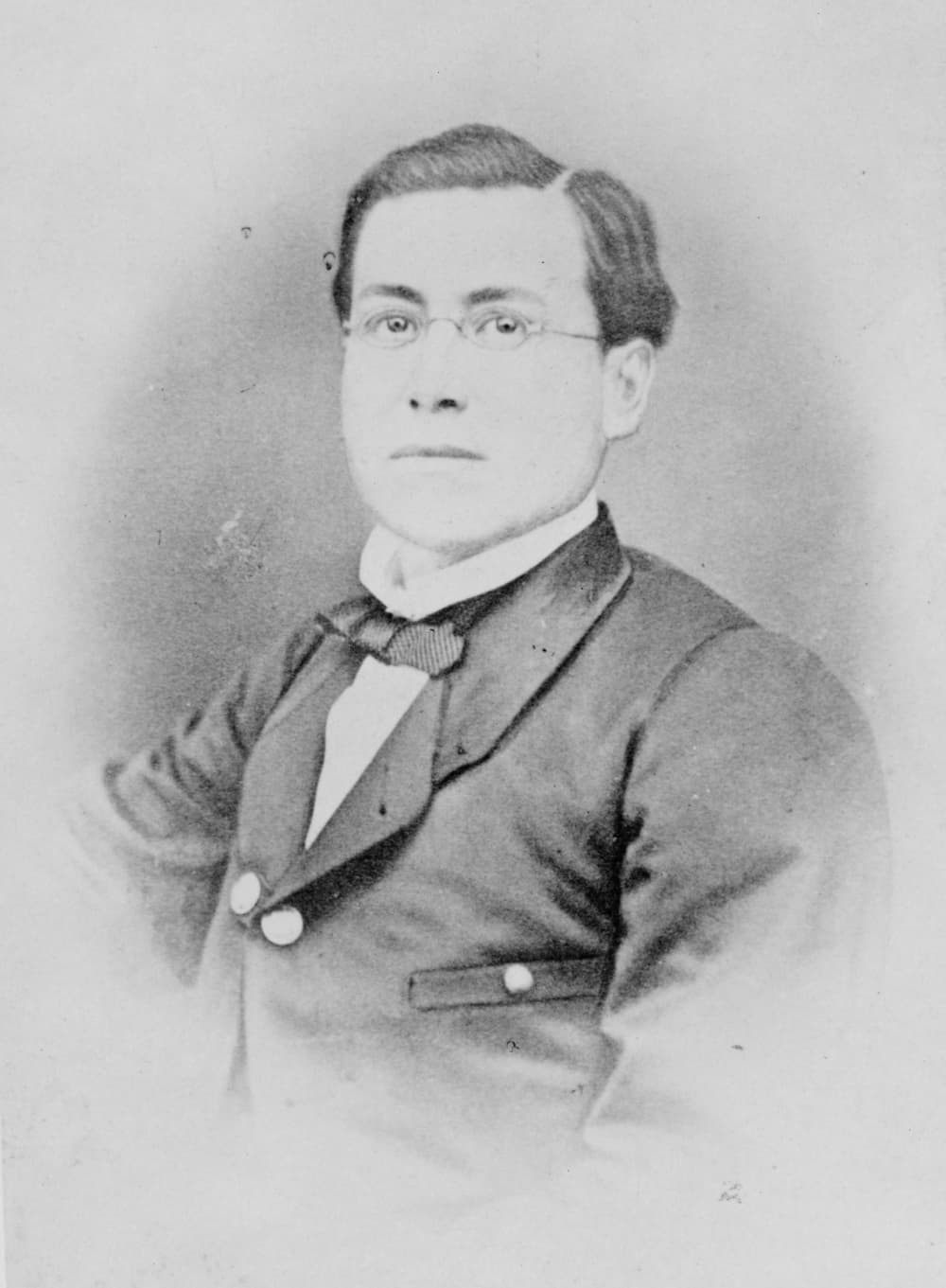

Dancers in colorful costumes are traditional sights at Cinco de Mayocelebrations. Mexican Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín, best known for his unlikely defeat ofinvading French forces at the Battle of Puebla.

Mexican Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín, best known for his unlikely defeat ofinvading French forces at the Battle of Puebla.

No, it's not Mexican Independence Day.

Actually, Cinco de Mayo commemorates not the declaration of independence from Spain but the struggle of a young country in the New World to maintain its independence from the old powers.

In 1861, Mexico's President Benito Juarez suspended payments of interests on loans taken by a previous regime from France, Spain and Great Britain. The three countries, arguably the largest military powers in the world at the time, decided to unite and force Mexico to pay back the money it owed. By the end of the year, Spanish ships from Cuba sat at Veracruz, Mexico's largest port, joined soon after by ships from France and Britain, in a not-so-subtle threat to Mexican sovereignty.

With the arrival of the French army in spring of 1862, and the support of conservative Mexican monarchists, goals changed from merely the recovery of loans to the occupation of the country, with the French having a particular eye on the mining resources in northwest Mexico.

After several skirmishes between the Mexican army and the French, the forces met on May 5, 1862 at Puebla, one of the largest and most important colonial cities, located directly between Veracruz and Mexico City. The French attacked the city from the north, but miscalculated their resources and the amount of support for the Mexican Republicans camped inside the city walls. By the afternoon the 33-year-old Mexican Commander General Ignacio Zaragoza Seguín had his cavalry attacking the French from both the right and left, while troops hidden along the path of retreat inflicted additional damage.

By the end of the battle, the Mexicans not only held the city but also inflicted heavy damages on the French, with 462 killed, over 300 wounded and 12 captured compared to only 83 Mexicans killed and 130 wounded.

Unfortunately for the Mexicans, one battle does not make a war. Though the French were slowed, they successfully continued their invasion and took the capital of Mexico City in 1863, forcing Benito Juarez's government into exile in the northwest frontier of the country.

The French installed Hapsburg heir and Austrian Archduke Maximilian I on the throne as the Emperor of Mexico, with his wife Charlotte, the former Princess of Belgium, renamed Carlota, Empress of Mexico.

But the old powers had overplayed their hand. Mexican Republican victories started to take hold by 1865, and with the end of the United States' Civil War, President Johnson was able to dispatch 50,000 troops to the border, ready to defend Juarez's government and Mexican sovereignty.

As Republican victories continued, the French began to withdraw in 1866, though Maximilian was reluctant to give up the capital. When Mexico City was overtaken, he attempted to escape through enemy lines but was captured and, mimicking his own "black decree" policy of immediately executing all Mexicans captured in the war, he was summarily executed by firing squad. Mexico had won the war.

Cinco de Mayo has a long and illustrious history of celebration in Mexico — that, is, if you ask someone in Puebla. Outside of the city, the holiday is virtually unknown in Mexico. But since the 1960s Cinco de Mayo has taken hold in the United States and around the world as a day to celebrate Mexican culture — and yes, a great excuse to drink margaritas.

So go ahead, raise a glass today to Benito Juarez. You should know who you're drinking to.

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook