Painting Outside

'Incomparable' new exhibition at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston makes grand impression

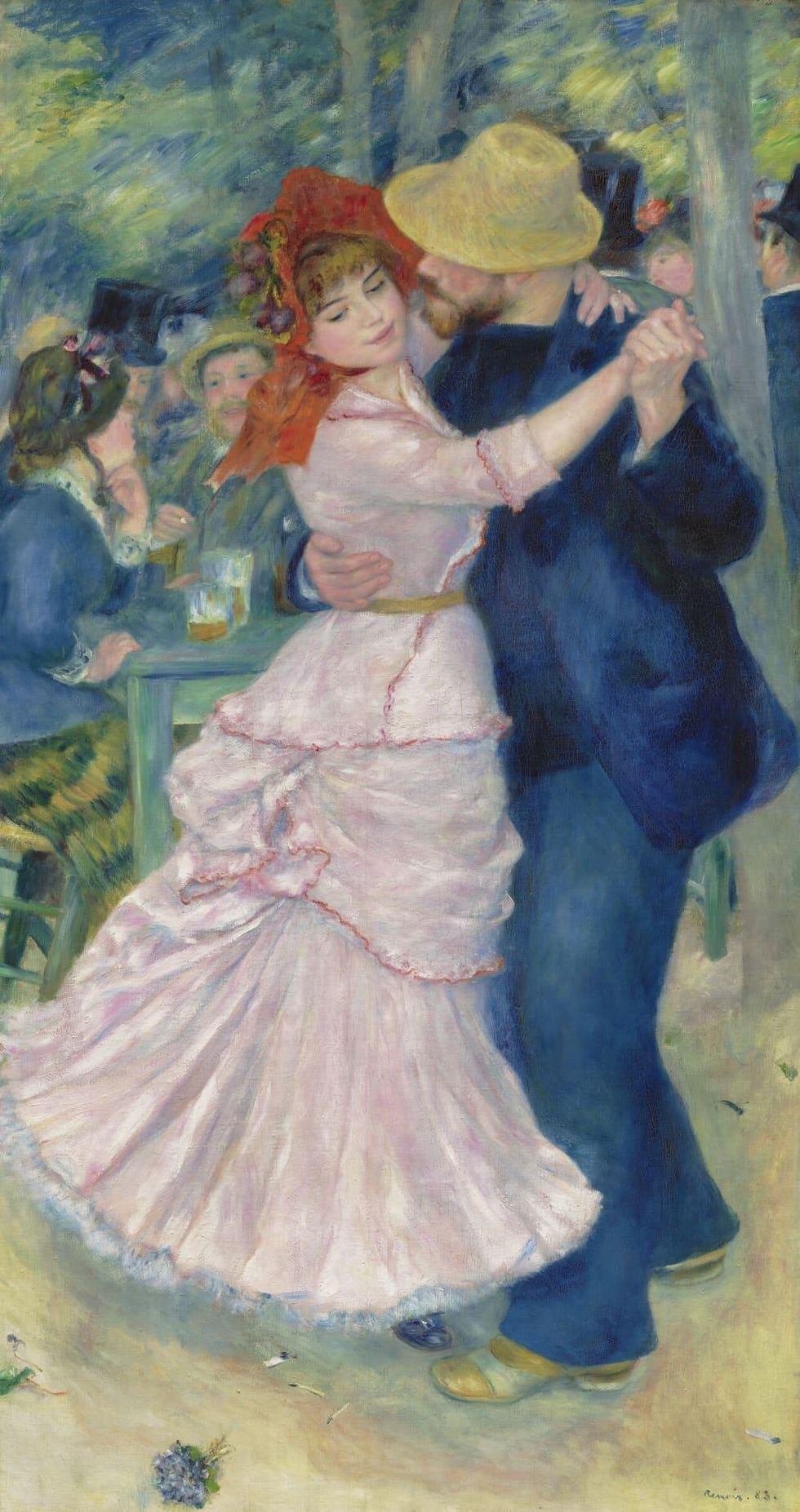

It’s as though we’re dancing right next to them and being witness to a coquettish moment between a fair young woman whose flowing dress twirls with perpetual motion and a bearded man whose intentions are, shall we say, somewhat questionable. She’s wearing a wedding ring. He’s not.

So what’s the 411 here?

It certainly makes this viewer want to get a glimpse of what happened before and after. Perhaps join the convivial group just behind them, grab a frosty mug of suds, and peep to see what ensues.

In Dance at Bougival from 1883, Pierre-Auguste Renoir doesn’t reveal the story so don’t be apprehensive about visualizing your own. The title painting of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s exhibition "Incomparable Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston" is on view through March 27, 2022. There’s so much about this painting that depicts why this aesthetic movement relates to so many.

The subject matter isn’t religious, historical or allegorical. It wasn’t commissioned by clergy or by a princely consortium to serve as a statement of morality or to glorify an army general with self-confidence issues.

It’s two people. We don’t know who they are but they’re doing what two people might do in the city on a weekend evening. And there’s beer. Of course we’re all wondering what might happen after such a dance?

If you’re looking for experiences that tell a story, even how the meritorious collection found safe passage to Houston is one for the books. “Incomparable Impressionism” was on view in Melbourne when the pandemic sent the Australian city into lockdown.

With no eyes to enjoy these paintings, MFAH engaged in talks to add Houston as an unplanned destination, and with additional and last-minute financial support from the Kinder Foundation and PNC Bank, which acquired BBVA earlier this year and itself had an impressive corporate art collection, voila. Add this to "Calder-Picasso," "Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer," and 'Afro-Atlantic Histories" to a notable list of MFAH's temporary exhibits.

MFAH curator of European Art Helga Aurish frames "Incomparable Impressionism" as a textbook explication of the trends that gave rise to an aesthetic movement that speaks to everyone. The realism of the Barbizon school—its namesake a village in France on the outskirts of the deciduous forest of Fontainebleau—in the 1840s moved the painter’s creative space from the studio an al fresco setting.

Newly available premixed oils also made it simple for painters to trek with their creative tools en plein air to capture ambiance and environment. Barbizon artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is to the Impressionists what Haydn is to Mozart and the string quartet genre. His work elevated landscapes, alongside the contributions of Narcisse Diaz de la Peña and the naturalism of Théodore Rousseau.

The bourgeoning of the middle class and the emergence of the concept of art collecting resulted in the production of smaller canvasses. As wealth shifted from princely sources to the mercantile class, paintings were now destined for the homes of these new connoisseurs. This thirst for owning art as demonstrative of socioeconomic status also created a new profession, the art dealer, and a new destination, the art museum.

The show moves from themes of the garden to the sea with marine artists like Alfred Sisley and Eugène Boudin, who were attentive to atmospheric effects on water and sky. Their technique renders a canvas in which these elements change in front of your eyes. Boudin’s Deauville at Low Tide of 1897 achieves exactly that, with figures along the shoreline and tiny sailboats on the ocean.

But none of the subjects are of importance.

Boudin also recognized the talent of a young Monet and showed him the pleasures and challenges of painting outdoors. But, for Boudin, some of the tendencies of his contemporaries were too radical and tempered his approach to the Realism of the era.

Aurish remarks that one of the defining characteristics of Impressionism begins with the layering of the paint. Old masters work with a dark background and layered lighter colors on top. Impressionist artists preferred a white background, building up to darker hues.

The Impressionism story continues with Renoir, whose Woman with a Parasol and Small Child on a Sunlit Hillside, c. 1874-76, displays his feathery brushstrokes in stark contrast to Monet’s thicker dabs and dashes. While the two of them were friends, others were not so friendly. An exhibition placard explains that Edgar Degas criticized Renoir describing that "he paints with balls of wool." Degas’ At the Races in the Countryside of 1869 appeared in the first join Impressionist exhibition held in Paris. The painting’s composition and perspective nods to Japanese art and the philosophy that not all elements need to appear in the center or within the frame, for that matter.

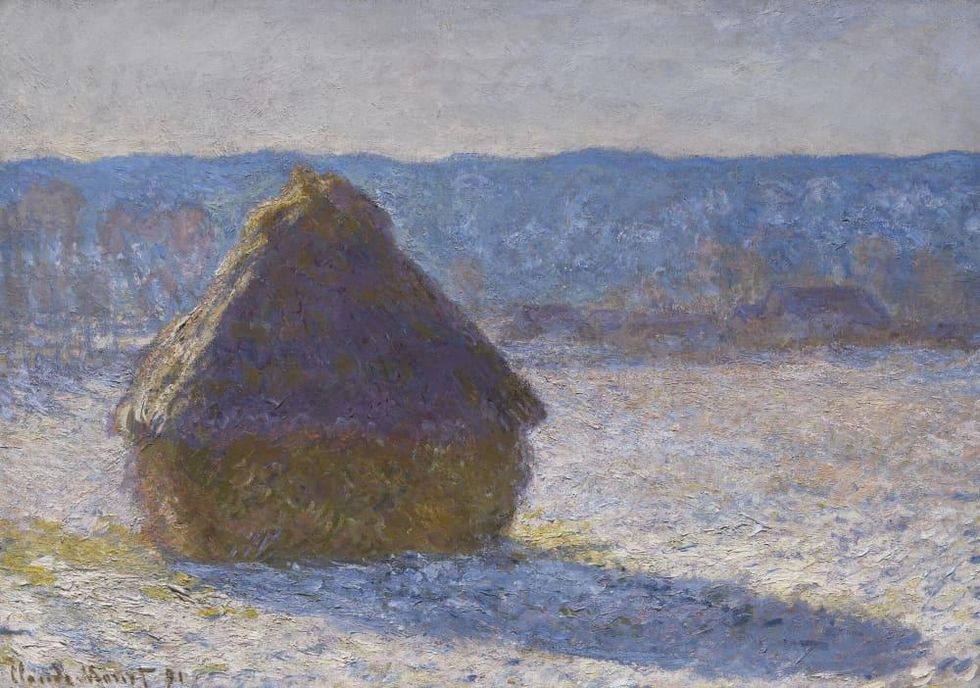

When you take into account Cezanne’s still lifes; Monet’s grain stacks, water lilies and bridges; and Van Gogh’s winding roads, the story of Impressionism and post-Impressionism—as told by this exhibition—isn’t linear nor singular.

The commonalities are found in the handling of light, the everyday subjects, and the illusion of the passing of time.