The CultureMap Interview

Leading the good fight: Oscar winner explains how America can get rid of racism — once and for all

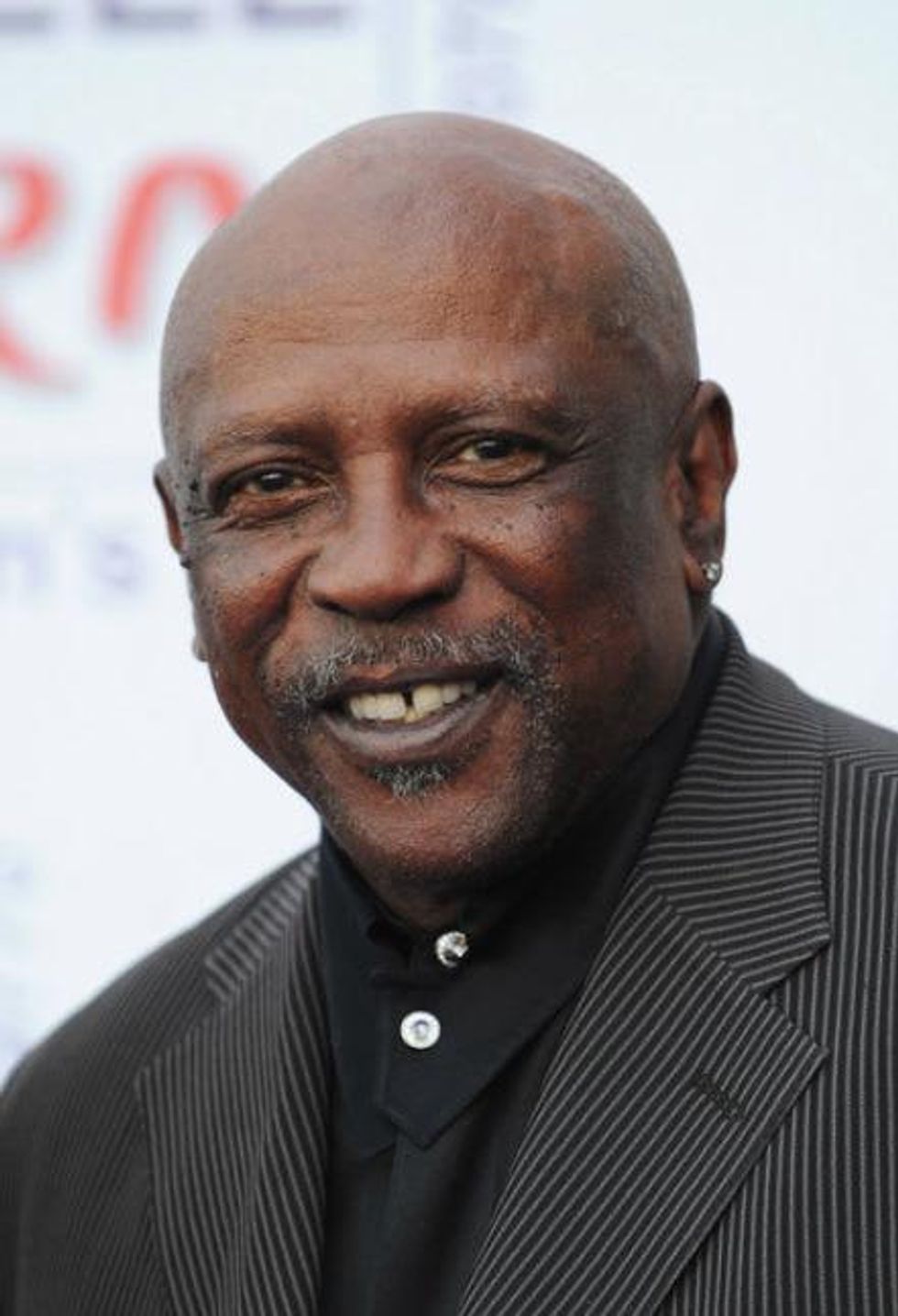

At 78 years old, Louis Gossett Jr. says he feels better than ever — both physically and spiritually.

The actor and founder of The Eracism Foundation, best known for his roles as Emil Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman and as Fiddler in the television series Roots — more recently as Halle Berry's dad in the CBS sci-fi drama Extant produced by Steven Spielberg — is in the midst of rehearsals for "Houston In Concert Against Hate: A Theatre Tribute to American Civil Rights," an event presented by the Anti-Defamation League set for 8 p.m. Thursday at the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts.

"I have to be the example because children have see-through vision. They know when you're truthful, and that starts really young."

As master of ceremonies, Gossett will contribute to an evening that spotlights inspiring stories of those who've made a difference in advancing civil rights, alongside performances by the Alley Theatre, Asia Society Texas Center, Celebration Theatre, Main Street Theater, Stages Repertory Theatre, Talento Bilingüe de Houston, Ensemble Theatre, Theatre Under the Stars and the University of Houston School of Theatre and Dance.

At the lobby of the Omni Hotel, CultureMap chatted with the Emmy- and Oscar-winning actor to learn more about the experiences that led him to become a proponent of civil rights for all.

Gossett's brown suit with a Nehru collar speaks of his mantra to promote cultural inclusively, his black T-shirt with an Eracism emblem sharing his place as an advocate for a world where racism is history. But his amulet, a mandala gifted to him by a lady who practices Buddhism, helps him gain spiritual clarity to stay on path.

CultureMap: In your 1983 Oscar acceptance speech to acknowledge winning Best Supporting Actor for An Office and a Gentleman, you mentioned that your great-grandmother lived to be 117 years old. Did you spend much time with her?

Louis Gossett Jr.: Every day and every summer. My mother and father and my cousins' mothers and fathers had to work three or four jobs a day, much like in the film The Help. They were butlers, chauffeurs, maids and porters. Someone had to take care of us, and that was the elder ladies.

They were the disciplinarians, they did all the washing, the best cooking I've ever had. If someone got sick, they went to the backyard. Even though they didn't know how to read and write, they knew about cures. It was that kind of society — we took care about one another. I was in my early 20s when she passed.

CM: What values did she impart on you?

LG: She had old habits because she came from the South. As soon as you were able to look, see and feel, you were responsible for something for the benefit of the community. At 3 years old, maybe you would gather eggs; a little older you would milk a goat. At her age, she was my mentor, the mother figure. That's what I am to my family now.

She taught me that. I have to be the example because children have see-through vision. They know when you're truthful, and that starts really young. It's instinctive.

CM: Was there a point in your life when you realized that some looked at you differently because you are African American?

LG: My neighbors, who came from all sorts of backgrounds, took really good care of me. In the business, I grew up with Steve McQueen, Marlon Brando, Martin Landau, Jimmy Dean — we were poor together. None of the stereotypes were apparent to me even though I knew that racism existed.

In 1966, I left New York and went to California, flew first class, was treated with style. A limousine picked me up from the plane and took me to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where I stayed in the presidential suite. I am sure they thought I was an African diplomat.

They had a rental care for me, a Ford Galaxie 500 hardtop convertible — eggshell white with leather interior.

"If we compare America to other cultures, even though we think we're No. 1, we are teenagers in comparison."

Do you know how long it takes to go from the Beverly Hills Hotel to Creston Drive? About 20 minutes. It took me four-and-a-half hours. I met every policeman in the neighborhood. They had me inside their cars, held up on the sidewalk and at night I ended up handcuffed to a tree for two hours.

I had traveled through Georgia and through Louisiana before, but the first time I experienced racism was in Los Angeles.

CM: What did you do?

LG: I called my mother who was in Brooklyn. She said, "I'll be right there," protective mother that she was.

She knew about the history of the South, of course, but this was different. This wasn't Hollywood, which really came out of New York. This was a problem in the police department in Los Angeles, though I had the same problem at work with some of the blue collar workers. The people who were famous, of course, embraced me. Others did not; it took me a couple of years later to figure that out.

I knew I had something to do. It was up to me to defeat their fear. So I thought, what can I do to make this better?

CM: What do you think is holding up this country from finally putting racism behind?

LG: We're young. If we compare our culture to other cultures, even though we think we're No. 1, we are teenagers in comparison — very powerful teenagers who still have a long way in believing what we created: One nation under God, indivisible with liberty and justice for all.

But we hardly practice it. We have to practice that. We need to take a chill pill and grow up, and some growing up is painful.

CM: Are you a man of faith?

LG: Absolutely. I believe in a God who gave birth to Jesus Christ and Mohammed — and so on — as examples for us to live by. It's to show us what's essentially important.

"If you take the time to learn about one another, about other cultures, we start caring more about one another."

Like how my grandmother used to say: A hard head makes a soft behind. The only lie she ever told was: This is going to hurt me more than it's going to hurt you. I never forgot it.

Something has to happen to me to pay attention. I have to stop and listen.

CM: You're in Houston to help the Anti-Defamation League honor leaders who've made a significant contribution in promoting and protecting civil rights, among them Benny Agosto Jr., Allen Becker and Renu Khator. But what can a regular everyday citizen do to help the cause?

LG: Get rid off certain defects of character, those that block our progress, so you can live the life you aspire to. If you do that everyday, it becomes a good habit. You have to be in a receptive position to get that message.

It starts with you, you have to make a decision of who you want to be before you can be an example to others. If you take the time to learn about one another, about other cultures, we start caring more about one another.

___

The Anti-Defamation League presents "Houston in Concert Against Hate" on Thursday, 8 p.m., at the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets start at $50 dollars and can be purchase online.

At the Omni Hotel, CultureMap chatted with Louis Gossett Jr. to learn more about the experiences that led him to become a proponent of civil rights for all.