A Sachertorte of a show

Furniture or art? Fascinating MFAH exhibit examines opulent style of "modern" Vienna

It’s uber-elegant, magnificently crafted and sinfully alluring, like the Porsche 911 classic you lust for while staying true to your boringly affordable American sedan. Is it furniture, or is it art? Or could that sumptuous Sachertorte of a wardrobe, on display in an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, possibly qualify as both?

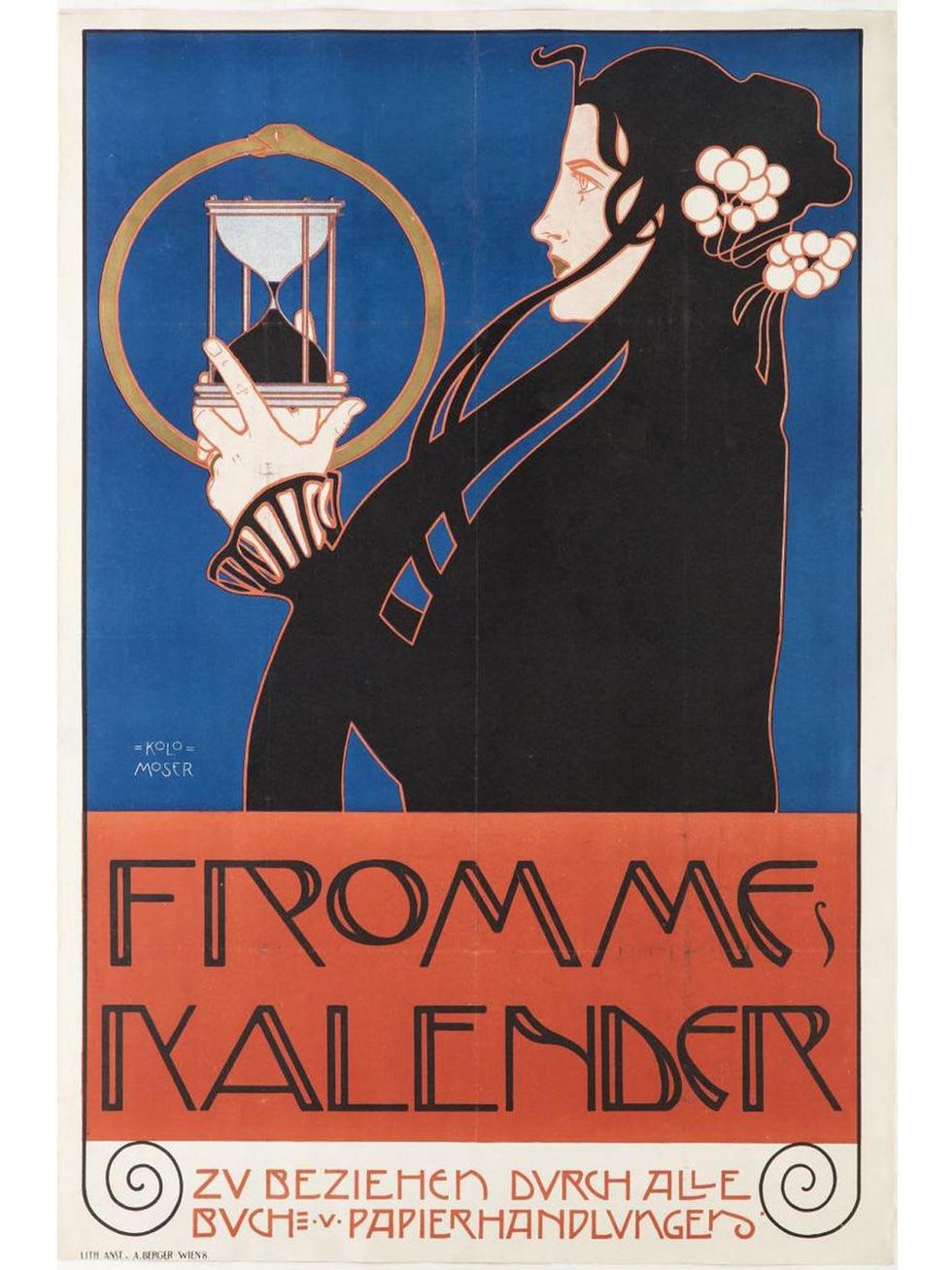

Indeed, it could. See for yourself in the delectable exhibition, “Koloman Moser: Designing Modern Vienna, 1897-1907,” on display through Jan. 12.

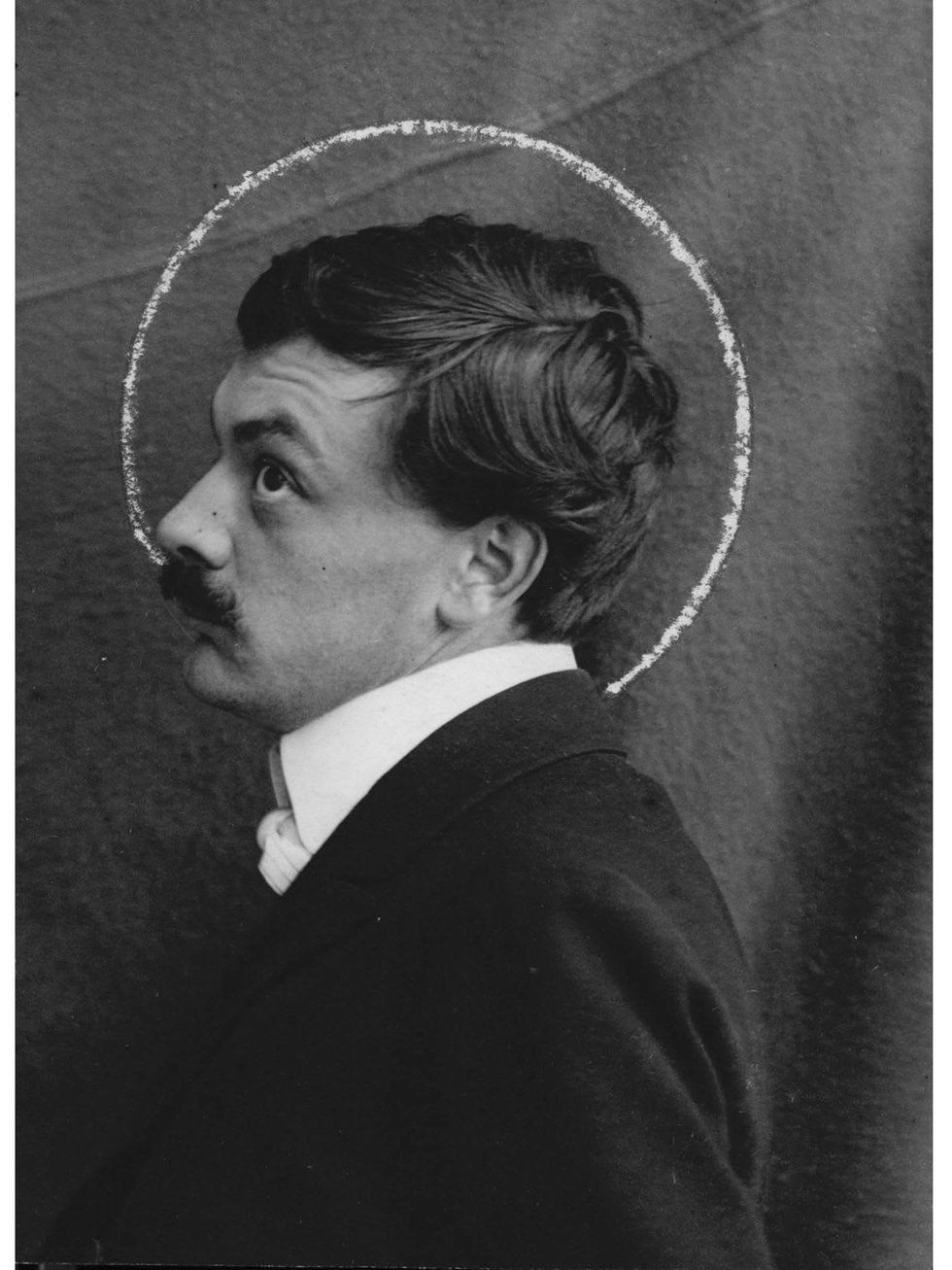

My appetite to see master designer Moser’s imaginative design scheme for an all-new Vienna at the turn of the 20th century was whetted by The New York Times’ in-depth review, praising this “gorgeous” exhibition when it premiered at the Neue Galerie in New York before coming to Houston.

More than 200 intriguing objects include the most opulent Viennese furniture and jewelry, elaborate metalwork, lovely vases, fine glasses and ceramics, as well as textiles, prints and wallpaper.

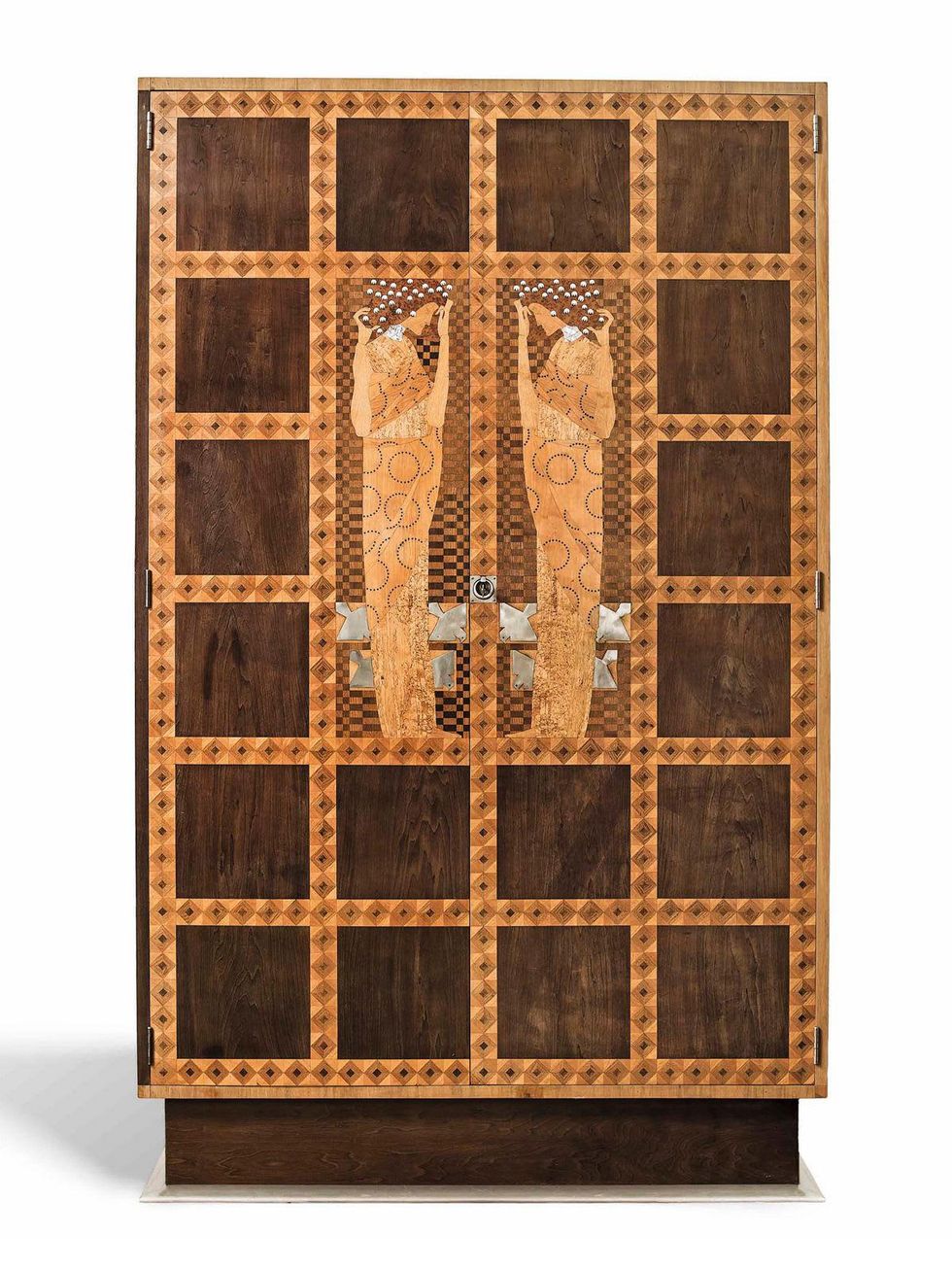

But what really drew me into this exhibition was the elaborately designed, carefully crafted, print and drawing cabinet dated 1903, standing sentinel outside the entryway. To call this piece a mere cabinet would be a misnomer bordering on insult. In fact, it’s a breathtaking masterpiece, a work of art and precision woodworking executed by master craftsmen, that beautifully serves a useful function. It’s an inspiration – as it was meant to be.

Imagine an Art Nouveau-style goddess decorating each door of a cabinet covered in splendid marquetry, artfully woven of the finest satinwood, rosewood and maple, touched here and there with mother-of-pearl. Think of the close collaboration required between the artist and the maker, Portois & Fix, in producing this marvelous tour de force. Imagine the countless hours spent assembling these extraordinary marquetry designs in wood — all the loving pride that went into this creative labor of love.

Intriguing objects

Inside the exhibition galleries, I discovered from the informative wall text that Moser was inspired by the Belgian and French Art Nouveau movement. He took the curvilinear style and developed his own planar style, ultimately creating a “distinctly Austrian modern style” that spelled out a whole new living environment.

More than 200 intriguing objects tempt the eye in this fascinating exhibition, encompassing the most opulent Viennese furniture and jewelry, elaborate metalwork, lovely vases, fine glasses and ceramics, as well as textiles, prints and wallpaper.

Taken together, the exhibition convinces you that you’re enjoying the best of Vienna at the turn of the 20th century, when the city was the cultural epicenter of central Europe. All that’s missing is a Strauss waltz and a little strudel.

It all started in 1897, when Moser, artist Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann and several other design rebels founded the Vienna Secession to create a modern new Austrian style in which the fine arts and applied art would be of equal value. The designer' noble goal, I learned, was to heal the world of the negative esthetic and social consequences of the Industrial Revolution. This led to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, in which “all aspects of daily life were to be given artistic form.”

My only question was: Whose daily life? From what I saw, I can only assume this daily life was being led by the silver-spoon-fed uppercrust of Viennese society, given the probable expense of these precious treasures. Just think, no plastic in those days. Probably no layaway plan, either.

Designer collective

With backing from a financier, Moser and Hoffmann founded the Wiener Werkstatte, or Vienna Workshop, in 1903. This collective gave designers and artisans a heady new creative freedom, working in an experimental environment to achieve their lofty goal. It looks as if Moser did quite a good job in that regard, based on all that you'll see in the exhibition.

For example, check out the 1902-03 vitrine with beveled-glass panes set into the finest ebony, Swedish birch and coral wood, decorated with miniature mother-of-pearl female figures. It’s part of a set of furniture that Moser was commissioned to design for a newlywed couple in 1902 by the indulgent (and obviously affluent) father of the bride. Each piece of furniture, marked with distinctive geometric patterns, makes its own dramatic statement through the use of luxurious marquetry and various types and tones of wood, with mother-of-pearl and ivory decoration, as Moser specified.

My favorite piece in the whole exhibition is a splendid wardrobe bearing the most arrestingly intricate maple marquetry.

I was obliged to resort to my lorgnette to lovingly analyze every delicious detail of the writing desk made of thuja and satinwood, its wonderful marquetry bearing an Egyptian lotus design motif. Moser designed the squarish chair to fit snugly, like a drawer, into the center of the desk.

But my favorite piece in the whole exhibition is a splendid wardrobe bearing the most arrestingly intricate maple marquetry. Each of its doors depicts, mirror-like, a goddess in a flowing robe, her hands gracefully touching the mass of hair piled atop her head, her face adorned with an enigmatic Mona Lisa smile. Her head is bent, her eyes are closed as she smiles demurely, acknowledging the attention of an ardent admirer.

Each diva is comprised of astonishingly complex, painterly marquetry derived from many pieces of different types and tones of wood. Tiny circular ornaments of ivory, like stars, dot her abundant hair, while a wide mother-of-pearl band surrounds her neck. Below, a series of metallic doves in flight accents the mystical nature of the total picture.

I thought I recognized that cat-swallowed-the-canary smile and Greek-goddess style from Gustav Klimt’s famously exotic portrait paintings, which are as complex and richly detailed as Moser’s furniture. More specifically, the female depicted in duplicate on the wardrobe struck me as bearing a marked resemblance to Klimt’s sweetheart, frequent model and muse, Emilie Floge. She was a designer who, with her two sisters, founded a high-fashion house in Vienna in 1904 that became all the rage with the same social set that could afford Moser’s furniture and other luxe creations.I remembered her special smile from seeing her photo in an informative exhibition-related lecture presented by architects Dietmar Froehlich and Celeste Williams.

Another captivating showpiece is a 1906 marbled-gold paper folding screen, its panels depicting stylishly dressed, Gatsby-looking ladies painted by Therese Thethahn. In the same room is an impressive black-and-white clock of ebonized wood, lavished with mother-of-pearl half-discs and brilliant silver, which was made in honor of a 1905 wedding. I wouldn’t dare wind the thing, personally. (Leave it to Franz, the butler.)