Visiting Mummy

Visiting Mummy: Special exhibition wraps up unique view of our fascination with the dead

Mummies. For some, the word might conjure images of homemade Halloween costumes, tame horror movies or silly adventure-flicks, but the Houston Museum of Natural is trying to dispel such misconceptions with Mummies of the World: The Exhibition, an informative yet fun examination of the science of mummies. The exhibition, touted as the largest traveling collection of real mummies and related artifacts, allows visitors to walk among the dead and discover how often mummification becomes just one last stop on nature’s life cycle.

I recently headed down to the museum for a special tour of Mummies of the World with expert guides Dirk Van Tuerenhout, HMNS curator of anthropology, and James Schanandore, the exhibition’s curator. Before viewing the galleries I knew would feature shrunken heads, mummified cats and bog bodies, I worried the macabre and bizarreness of the subject matter might overwhelm the experience.

I soon found with its focus on the process of corpse preservation along with a respect for the varying cultural attitudes towards the dead, the exhibition does much to show that mummification is sometimes a very natural part of death.

Mummy-kinds

Organized thematically more than by geography, Mummies of the World is divided by the two different types of mummies, naturally created mummies and anthropogenic (human-created) mummies, with examples from both categories on display and all equally fascinating.

Nature and environmental factors mummify the dead more often than human cultures have. Mounted texts, videos and interactive stations within the galleries give easily understood lessons on the process of decay. The key ingredients needed for decomposition are water and oxygen. Whether they are intensely cold or hot, dry environments can imbed bacteria from beginning the process of breaking down organic material and instead bodies become dried and mummified.

Meanwhile, some great civilizations like the ancient Egyptians succeeded in artificially preserving bodies. While modern mortuary practices embalm the deceased for the living to view one last time, Egyptians wanted to preserve the dead for immortality since they believed the body was the house for a soul.

Nature and humans have sometimes clashed in a strange struggle over the dead, as one culture might strive to return the body to the earth while environmental factors instead preserved the flesh. In other places and time periods people established rituals and methods for preserving the body from natural decomposition.

Forces of Preserving Nature

Within the galleries displaying naturally preserved mummies we get to know the stories of individuals and even families whose bodies over the centuries withstood decay because of the dry conditions within the crypts where they were laid to rest. The exhibition begins with Baron von Holz, a 17th-century nobleman, who’s still wearing some fantastically enduring boots, and ends with the Orlovits family–mother, father and son–who all died from tuberculosis in the early 18th century. Scientists have even been able to study the inert bacteria still present in their lungs.

I also found the galleries filled with nameless mummies, those without records and stories, like two Peruvian child mummies and the remains of a woman found in a bog in the Netherlands to be most sad yet somehow beautiful.

Humans Raging Against the Dying Light

About half the galleries focus on human attempts to combat death’s decay, with a special focus on Egyptian practices. HMNS visitors will likely find the fully intact mummies Nes-Mer and Nes-Hor, satisfy all their classic mummy expectations. The exhibition even gives us some background on the lives of these exhibition stars along with a fascinating look into Egyptian burial practices. Look for wall text information on the mummified animals entombed to join the dearly departed into the great beyond.

But these thousands-of-years old mummies have competition from the 22 years-young whippersnapper, MUMAB a.k.a the Maryland Mummy. In an attempt to replicate ancient Egyptian practices, scientists at the University of Maryland at Baltimore preserved the body of an elderly man who had donated his remains. The MUMAB room allows viewers to pay their respect to a modern man treated in death like a pharaoh.

Mummies of the World does try to explore the whole world and even gives insight into the shrunken head trade in South America. (In the mid-19th century Europeans were so taken by the practice, they created replica shrunken heads from unclaimed bodies.) We also can view a mummy head from Vanuatu, the South Pacific Island near Papua New Guinea. The culture so revered their ancestors they smoked the heads of deceased, painted them and kept them close to watch over the living.

In the end, the exhibition tells us as much about the human relationship with death as it does how the dead preserve.

Mummies of the World: The Exhibition will be on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science until May 29, 2017.

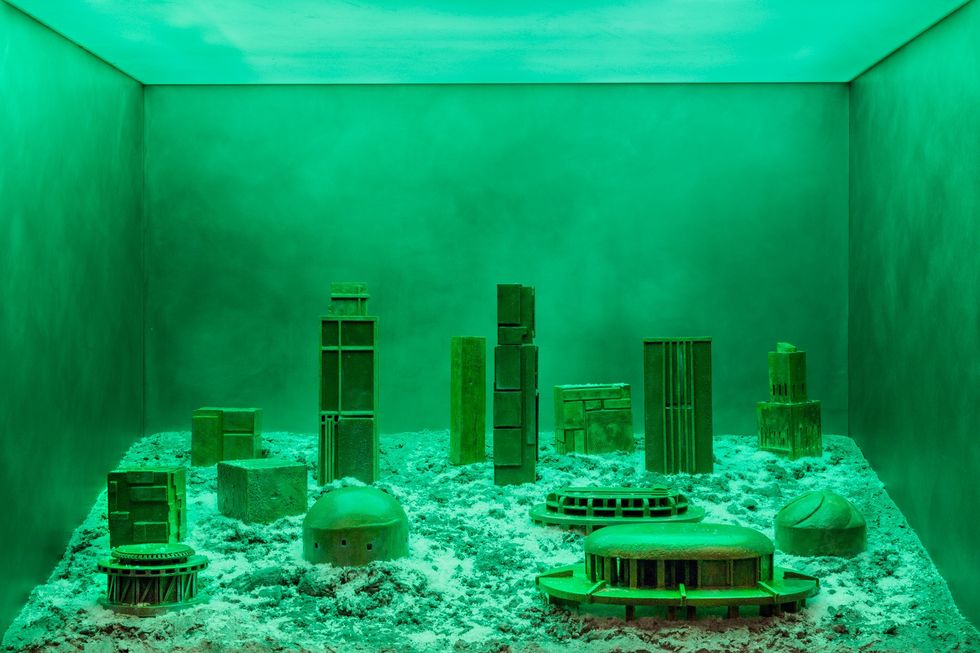

!["Mami Wata Afrofuturism: 500 Years Back to the [Afro][F]uture"](https://houston.culturemap.com/media-library/mami-wata-afrofuturism-500-years-back-to-the-afro-f-uture.jpg?id=51962255&width=980)