Strange Eggs

Menil's subdued Claes Oldenburg exhibit raises questions about surrealism andbeauty

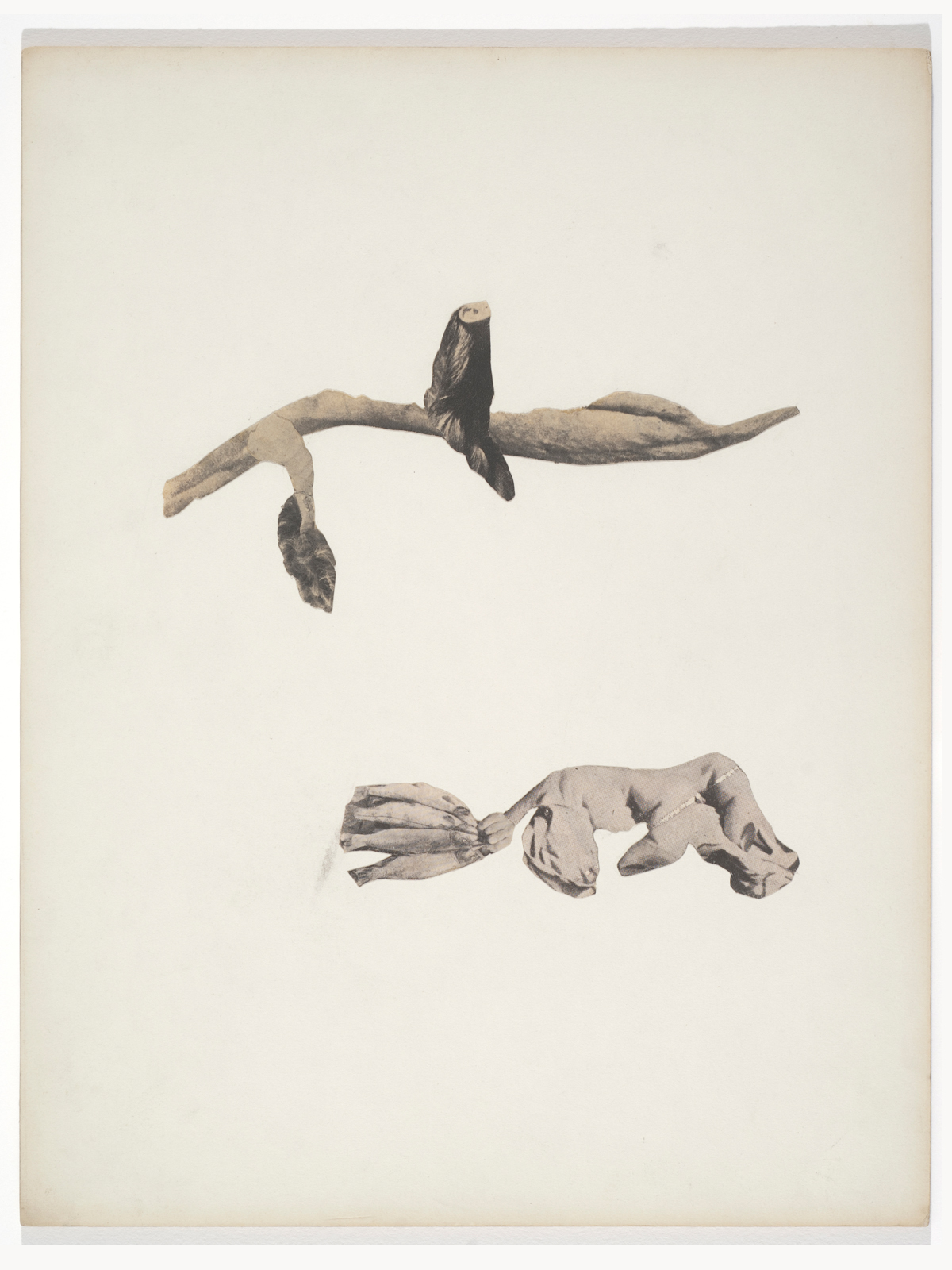

"Strange Eggs XVIII, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs XVIII, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen "Strange Eggs VIII, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs VIII, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen "Strange Eggs X, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs X, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen "Strange Eggs V, 1957,", collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs V, 1957,", collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen "Strange Eggs III, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs III, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen "Strange Eggs II, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

"Strange Eggs II, 1957-58," collage mounted on cardboard, collection of ClaesOldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

How strange should strange be?

When walking into a gallery dedicated to surrealism, one may find this a hard question to answer. Happily Houstonians can stroll into the Menil Collection and see a remarkable assemblage of works that finds oddity in the ordinary or that renders the bizarre commonplace.

What, then, to make of the Menil's most recent offering, Claes Oldenburg: Strange Eggs, curated by Michelle White and running through Feb. 3, 2013?

Oldenburg is no stranger to the strange, and one would be hard pressed to look at his "Spoonbridge and Cherry" at the Walker Arts Center and observe how the magnification of everyday objects changes how you see the world. Here, courtesy of the Walker, is a little walk down memory lane to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the installation of "Spoonbridge and Cherry," including a fantastic photo of a massive cherry hoisted by a crane.

So much of Oldenburg's work makes the familiar unfamiliar by playing with shape or scale: melting (or soft) drum sets, gargantuan hamburgers and apple cores, and binoculars big enough to shelter a car. The effects can be extreme for such simple things. A 16-foot vivid orange ice bag seems more likely to cause a headache than salve a throbbing muscle.

So much of Oldenburg's work makes the familiar unfamiliar by playing with shape or scale. The effects can be extreme for such simple things.

The fan of this Oldenburg might be a little surprised upon walking into the room in the Surrealism galleries that hosts "Strange Eggs I-XVIII." The surprise might be like the surprise of those who stumble into the Rothko Chapel for the first time, expecting a marvelous burst of color, and finding, instead, a palette intentionally muted, somber and conducive to meditation.

Strange Eggs dates from 1957 to 1958, early in Oldenburg's career, and lacks the playful shapes, shades, and scales of his well-known later works. Mounted on 18 cardboard panels, slightly yellowing and enclosed in plain birch frames, the collages are composed from black and white or sepia images cut out of old magazines. Some images are recognizable, others obscure. Each collage has an odd suggestion of wholeness or circularity, which perhaps explains why they're called eggs.

"Strange Eggs X" has a cake mounted precariously on what looks like a fish (or some other creature?) while nearby a small naked male torso is mounted on the body of a large cat sitting on some unidentifiable ruffled substance?

Or take "Strange Eggs XIII." Here we find a large pie with a slice cut out. Superimposed is the slice, although it's larger in scale than the pie, and hovers oddly over it. On the slice sits what looks like a fragment of a body or statue and above the body hangs what looks like a series of booted, marching legs. Another torso of different size floats nearby wrapped in leather, perhaps.

What's the value of Strange Eggs? Certainly, the early works of a legendary artists are worth attending to. Collage is a fine example of what was so distinctive about surrealist art across media.

Strange Eggs might also remind Houstonians of another recent showstopper. It's hard not to think of Mel Chin's marvelous "The Funk and Wagnall's A-Z" in the Station Museum's exhibition Artefactual Realities. Chin created a gallery full of startlingly precise floor-to-ceiling collages cut from a set of encyclopedias. I was not the only one to think of this. A group of young women passed through the room and one blurted out, "It's like Mel Chin, but not as beautiful." Hard to disagree.

Strange Eggs might also remind Houstonians of another recent showstopper. It's hard not to think of Mel Chin's marvelous "The Funk and Wagnall's A-Z" in the Station Museum's exhibition Artefactual Realities .

But this raises an important question. Is it somehow cheating the surreal to prefer a good dose of beauty? There's plenty of compelling ugly, aggressive, even obnoxious art. Oldenburg seems almost dull. I don't mean that it is necessarily boring but rather that it seems to make the viewer and the work of art disappear in the yellowing cardboard and gray images.

Curator White described this very aspect of the Strange Eggs: "They don't easily come to the surface. They're not easily readable. At this time, Claes Oldenburg was also writing poetry. He was composing his poetry of found textual fragments. In the same way, he was using found images. So if we want to figure them out at all, it's like how you read poetry. I like when things hang in that ambiguous space. I don't want to reveal what everything is, nor do I want to know."

Strange Eggs suggests we should be suspect of the desire for things gripping and obvious. The Menil built a marvelous collection of Surrealist art by avoiding what became the clanging and obvious surrealism of, say, Dali's dripping clocks, now hopelessly hackneyed through repetition.

What is perhaps more gripping than Oldenburg, however, is the reinstallation across the way from Strange Eggs. You'll find that Victor Brauner, Max Ernst, and Joseph Cornell have come out to play with some marvelous works by Robert Rauschenberg. White installed this room "to connect (Strange Eggs) to the larger use of photomechanical reproduction not only in surrealism but in the work of Oldenburg's peers."

Having just seen Strange Eggs I was drawn to Rauschenberg's beautiful shirtboards. Four hang together, silkscreen and collage on cardboard. My favorite "Untitled [Embryos]" features two large eggs with space for an absent third. When we consider how dense and even cluttered collage can be, it's fascinating how much space Oldenburg and Rauschenberg leave for the viewer.

An ambiguous space, perhaps, but maybe there's nothing really so strange about that.