The Review Is In

Houston Ballet's puzzling production of The Tempest offers too much noise, too little drama

“Full of noises” is how the creature Caliban describes the enchanted island of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. This magical, musical place is sometimes sweet, sometimes terrifying.

But “too much noise, too little drama” might be a better way of describing David Bintley’s The Tempest, a co-production of the Birmingham Royal Ballet that made its North American premiere and runs through June 4 at the Wortham Theater Center performed by Houston Ballet and set to a score commissioned from Sally Beamish.

Somehow there weren’t enough flying fairies, improbable props, or curious costumes to keep this ship afloat.

The Tempest may not be as well-known as Romeo and Juliet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but it has all the makings of great drama: an exiled duke with magical powers, a resentful slave and an enslaved spirit both longing to be free, a shipwreck, two young lovers, a palace coup, a harpy, several gods, a mutiny, revenge plots, murder plots, confessions, reunions, and a happy ending with a hint of ambiguity.

What else could you ask for?

How puzzling, then, to feel both under- and overwhelmed by the spectacle before me. There was so much activity I never had time to feel much of anything, which was its greatest flaw.

More and more was the principle of the production. If the original script calls for gods, add a few more. And if Neptune is going to appear (for no reason) he needs mermaids and mermen to dance furiously around him. And if Pan too appears (also for no reason) then he needs accompaniment as well in the form of rustic peasants in strange skirts and hats.

It was as if the minor figures of several other story ballets too had been shipwrecked on the island, and there was nothing else to do but dance their hearts out.

One of the understandable anxieties of this production clearly concerns whether the audience would know the plot. Program notes are not enough for any new story ballet, especially Shakespeare, unless the story is known by all. To compensate, the production opted for a drama-killing reliance on the overly literal, the overacted, the over-pantomined, and the over-stuffed (with props, and odd costumes, and stage effects).

A poor grasp of dramaturgy haunted the production as was evident late in the second act. A recollected scene reveals the coup that exiled the bookish Duke Prospero. We see Prospero melodramatically torn from his family, including an invented wife suspiciously named Prospera.

Is the little bit of melodrama she offers worth the questions she raises, like “If she’s there in the past, why isn’t she on the island?” and “Were there no other names available?” To introduce this important plot information so late in the game is also missed opportunity. A few fewer flying fairies and a few more informative scenes might have allowed the audience to absorb the story.

Bintley, who serves as artistic director of the Royal Birmingham Ballet, is no stranger to Houston Ballet, which staged the North American premiere of his Aladdin, a work, like The Tempest, that so busily fills every moment with stage tricks and predictable movement that there’s no time to experience anything. Bintely is a competent showman and choreographer but little feels distinctive about the movement. And what’s the point of rendering in choreography a story relatively few know but that anyone can read when that choreography is so forgettable?

Ballets based on Romeo and Juliet or A Midsummer Night’s Dream are most often defined by the iconic scores of Prokofiev and Mendelssohn respectively. No such icon exists for The Tempest, though Sibelius, Berlioz, and Tchaikovsky all tried their hands at it. Crystal Pite’s Tempest Replica relies on Owen Benton. Michael Nyman hauntingly scored the film Prospero’s Books, while Nico Muhly composed exquisite music for Stephen Petronio’s Temepst-ish “I drink the air before me.” Luciano Berio and Thomas Ades premiered musically experimental Tempests in 1984 and 2004.

In such company, Beamish’s claustrophobic score left more than a little to be desired. Unrelenting might be the best way to describe it. For extended periods, the music see-sawed between relatively narrow harmonic ranges. There was little subtlety or mystery. Sweet moments weren’t sweet enough while terrifying moments seemed merely loud. No song-like moments emerged to honor Shakespeare’s most musically conscious play. The resulting texture felt merely through-composed or incidental too often. Just as there was little time for the eye to rest in this busy production, so too for the ear.

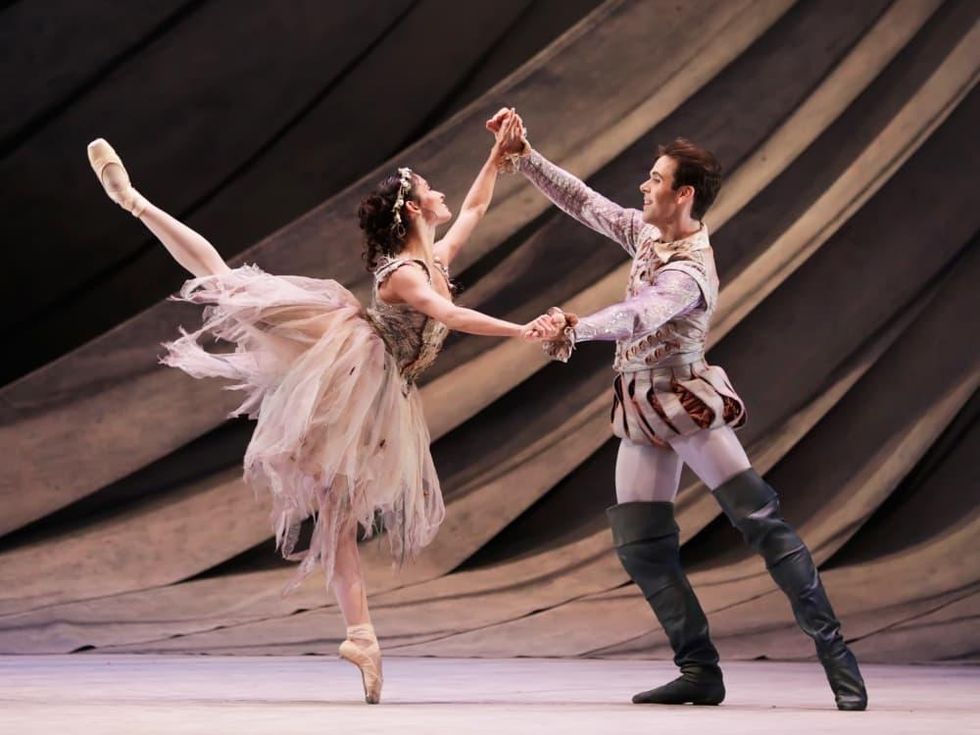

Houston Ballet’s dancers did their best with this distracted spectacle. Ian Casaday rarely disappoints and made for a rather spry and sexy Prospero. This odd directorial choice made him seem more Miranda’s love interest than her father. Derek Dunn battled a terrible wig and make-up and make for a wonderfully interfering Ariel. Karina Gonzalez and Connor Walsh executed lovers Miranda and Ferdinand well enough, though the characters were drawn too shallowly to convey the mix of wonder and grief that make them more than just callow youth.

What you wouldn’t know from this production is how deeply moving The Tempest is. People are so desperate for power they’ll kill. Fathers are so scared of losing their children it feels as if the world is ending. Some never have a home and always must serve at the pleasure of others.

The Tempest imagines a world in which our mistakes always haunt us in the end. At least in that imaginary world, if sadly not on the actual stage, there’s a chance for redemption.