The Review Is In

Houston Ballet's winter program offers two thrilling new additions and one celebrated clunker

If there is a common denominator at the heart of Houston Ballet’s current Winter Mixed Repertory Program, perhaps it has something to do with groups of men and women behaving together in highly stylized environments. Musically, the featured dances by Wayne McGregor, Jiří Kylián, and Jerome Robbins bear no obvious relationship. They don’t need to, necessarily, and I’m thrilled when dancing is free of narrative. When an artistic director puts three pieces together, however, the dances will either potentiate each other or have the opposite effect. Neutrality is off the table.

British choreographer Wayne McGregor’s Dyad 1929 for 12 dancers is a wonderful opener. Houston Ballet’s press release says the choreographer dedicated it to the memory of Merce Cunningham, though his Wiki-profile calls it “…one of two ballets that McGregor created to celebrate the centenary of the Ballets Russes” (the other one is titled Dyad 1929) for The Australian Ballet. To my eyes, the choreography looks nothing like Cunningham’s work. If we take the word “dyad” by one of its many meanings, namely, a two-person group, McGregor’s stage strategy becomes apparent.

With Lucy Carter’s stunning bright yellow horizontal lights (recreated for Houston Ballet by Simon Bennison), Moritz Junge’s nuclear-laboratory costumes, and Steve Reich’s pulsing and gorgeous Double Sextet as a thrilling foundation, Dyad 1929 is a highly appealing work. I wouldn’t call it experimental, but rather formally exact. The suddenly undulating spine that seems to move from one dancer to the next was already well-developed by Jorma Elo in 2009, when McGregor premiered this piece. There are many episodes of precise, dense partnering, not to mention virtuosic pointe work and intermittent unison phrasing that makes for a kind of punctuation of the phrasing.

The accomplished musicians of the Houston Ballet Orchestra, under Ermanno Florio’s expert conducting, gave Reich’s score a mostly confident interpretation. It is fiendishly difficult to play and wonderfully easy for listeners to enjoy. Reich used a sort of A-B-A, or otherwise palindrome form, with the slowest section in the middle. McGregor put a challenging pas-de-deux in this position. Elsewhere, he shows the six men and women in various permutations, including a section for just the women and another for only the men. This gives the feeling of an incredibly intricate etude. The dancers offered a devoted, clean interpretation.

Could it do with any improvements? Not in its interpretation by Houston Ballet, though I wondered about some of McGregor’s choreographic decisions. A deadpan walk seems the easy way to get dancers off and on stage, but it is at odds with the otherwise intricate choreography. Anna Sokolow was perfecting that kind of deadpan walk by the early 1950s, though in her hands it was extremely powerful. And if you put a grid of huge black dots on both the floor and the wall, shouldn’t you use them to organize the dancers more precisely? This seemed like a bit of a wasted opportunity.

Jiří Kylián’s ominous Wings of Wax followed, and it was clearly the high point of the program. Houston Ballet has been steadily building its repertory of Kylián’s ballets, which is thrilling for audiences. In this case, the dancers have taken on one of the choreographer’s darker and more challenging pieces. It’s not a crowd-pleaser, but rather something that challenges both performer and viewer with its perplexing, idiosyncratic organization of events.

The curtain rises on a white, upside-down tree floating in the center of the stage, just beyond the proscenium arch. It is circled by a roving spotlight, which resembles some kind of errant meteorite. Of course, it references the sun in the story of Icarus, upon which Kylián based his ballet. The dancing comes from four male-female couples, with sharp divisions at times between the men and the women. In one particularly stunning event, the women seem to freeze as the music changes from Bach to John Cage, while the men travel rapidly around them. It’s one of those moments (we saw plenty of them in Neumeier’s brilliant Midsummer Night’s Dream last year) where two vastly different realms co-exist within the same space.

As the music moves through various fragments — from Philip Glass’ String Quartet No. 5 and then an adagio from Bach’s Goldberg Variations arranged for String Trio — the dancing becomes increasingly lyrical, slower, as if it is attempting to disappear altogether. This is a timeless, archetypal work that is one of the most exciting dances Houston Ballet has acquired in many years.

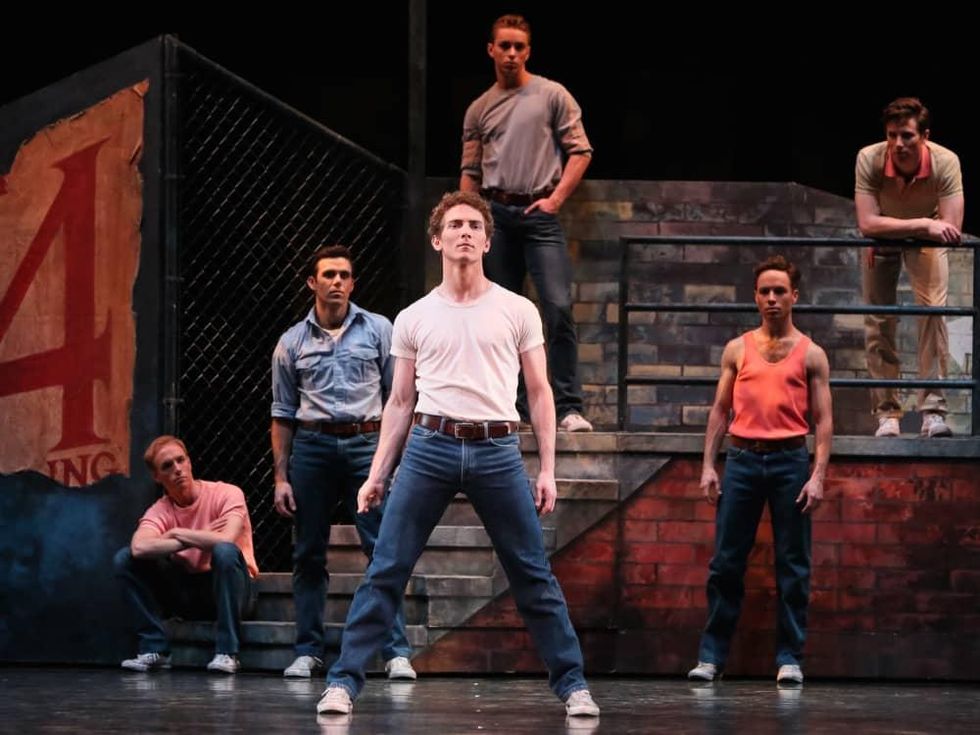

Oh, how I wanted to love the final work, Jerome Robbins’ West Side Story Suite. And oh, how it flopped on opening night!

The problems are numerous. As celebrated as it is, this ballet is embarrassingly dated. There seems to be something actually quaint about boys fighting with switchblades when street gangs today are fully stocked with automatic firearms. And do we really need to witness Houston Ballet’s women attempting to sing in hokey Puerto-Rican accents? Or better yet — is it in the least entertaining?

I won’t pick at Robbins’ choreography. It achieves its purpose, even if it is detached from the musical setting in which it originated. We could probably do with a little less stage combat. A few of the dancers, Rhodes Elliott in particular, proved themselves to be competent singers. West Side Story needs spectacular singers, however. And it was actually the “professional” singers who were the worst on opening night, in particular Jack Beetle, who went sour on every high note. Florio seemed to be over-conducting throughout, as if he were trying to rouse the necessary energy into the suite.

It was the sad scenic designs, the bad mugging and machismo, the forced merriment that made this piece unsustainable and an inferior companion for McGregor and Kylián. Please, give us some more Robbins, but steer clear of clichés. Why not his Goldberg Variations, his stunning re-interpretation ofAfternoon of a Faun, or even his legendary, creepy The Cage? Any of those would have made this program a thrilling triple-header.