Houston Heart History

Fascinating new book gets to the heart of Houston's place in medical history

Even as Houston grows ever more populous and gains national standing as a city of the future, we often see ourselves as a relatively new city. Yet, there’s great untold history hiding out there, waiting for curious men and women to find and tell the stories of those past Houstonians who worked to make the city what it is and will be. One not so small corner of untapped history is also one of our greatest resources, the Texas Medical Center.

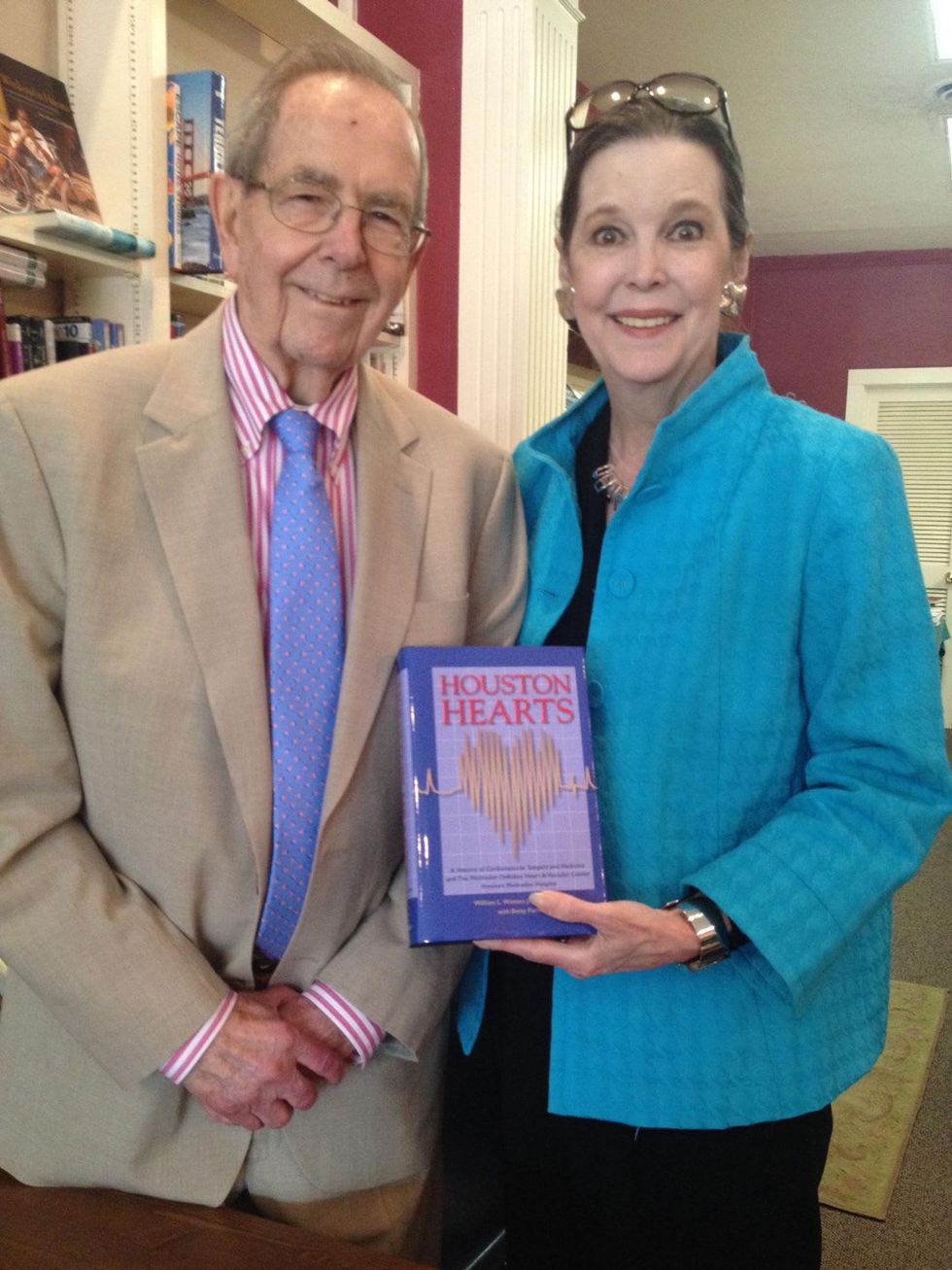

Recently, Dr. William L. Winters, a senior attending staff member in the Department of Cardiology at Houston Methodist Hospital, and Betsy Parish former Houston Post columnist and author of Legacy: Fifty Years of Loving Care, set out find some of those nearly lost stories. The result is their new book Houston Hearts: A History of Cardiovascular Surgery and Medicine and the Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center at Houston Methodist Hospital.

I spoke to Dr. Winters to get to the, well, heart of Methodist’s history and perhaps catch a glimpse into the medical future being built right now.

CultureMap: Your life certainly seems busy enough in the present. What was the impetus to delve through the history of cardiovascular medicine?

Dr. William Winters: My senior partner — now deceased — Dr. Don W. Chapman, reminisced often about the very rich history in the Methodist Hospital. We thought it would be a shame to let it disappear without making some effort to capture it. He and I agreed that I should start recording some of this history. I began by doing video interviews with people who had been in the cardiovascular field for many years and then expanded to other physicians and administrators.

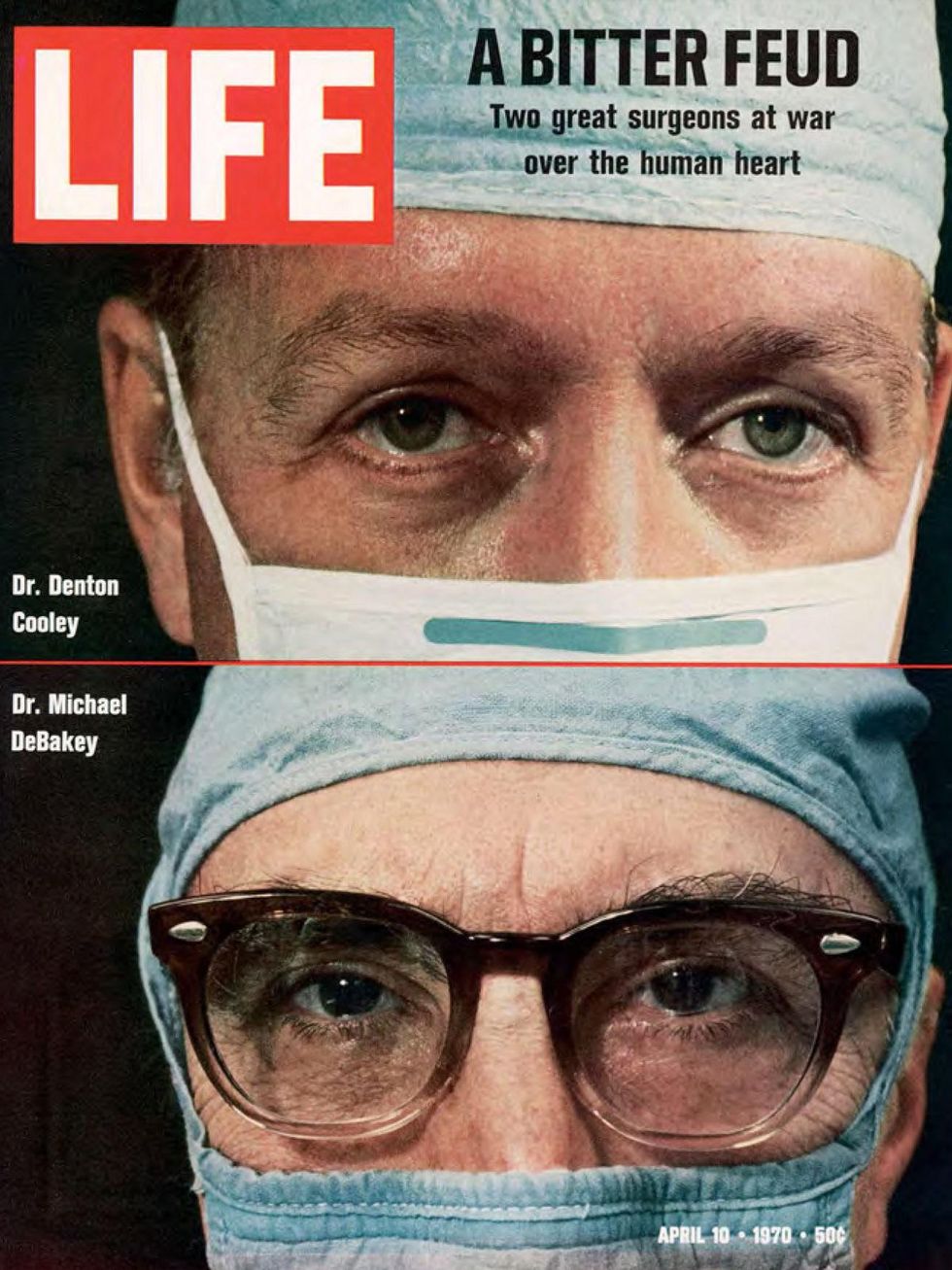

CM: In the beginning were you interested in staying with a focus on particular physicians like Dr. Michael DeBakey, who is a prominent figure in the book, or where you interested in a broader look at the whole history of Methodist Hospital?

WW: We always wanted to look at the entire history of cardiovascular history here. We didn’t have an endgame at first, but we later divided the book into three sections: the very beginning of the hospital in 1908 before it was Methodist to the mid-1940s (is the first section).

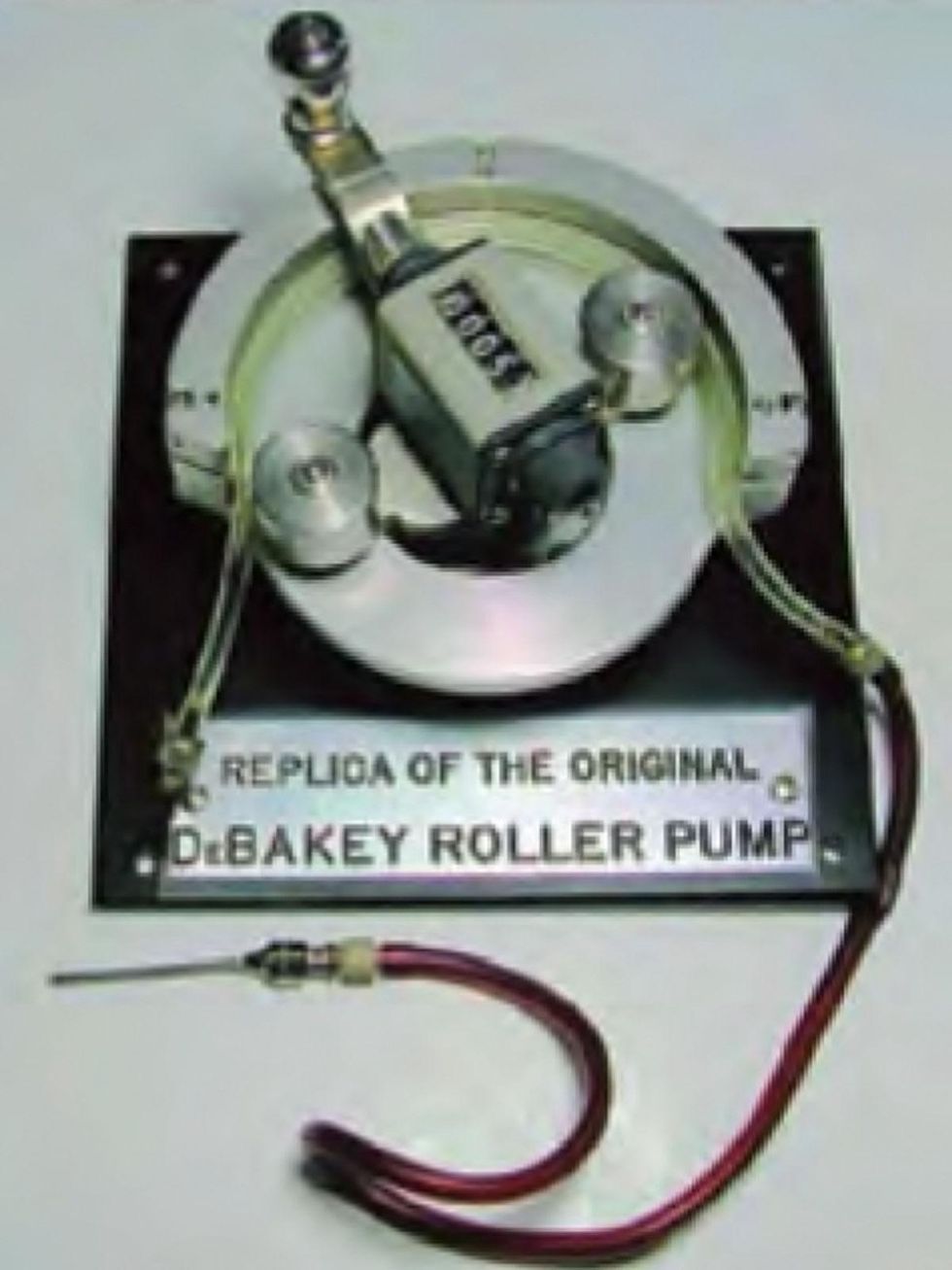

The second portion begins when Dr. Chapman came to Houston in 1944 and Dr. DeBakey came here in 1948. It was mostly cardiovascular surgery in those days and the surgeons were just going gangbusters developing ways to treat congenital or valvular heart disease.

The third part of the book basically dates from 1980 to the present when the cardiologist became the dominate figure in cardiovascular medicine. So we went from the hospital’s origins to surgeons’ early work to the cardiologists’ prominence.

CM: Some of the most amusing stories in the book come as short “blips” at the end of each chapter, which chronicle everything from early hospital trustee, Ella Cochrum Fondren’s ability to sniff out oil from mud samples to Frank Sinatra’s friendship with Dr. DeBakey. How do these little “blips” fit into the book?

WW: They were anecdotes that both I remembered through the years or that Betsy Parish encountered that didn’t fit well into the text itself, but we knew they would add color and sometimes humor to the end of the chapter.

CM: Did you and Betsy Parish discover anything through your extensive research that surprised you?

WW: A good deal of the history of Dr. DeBakey’s national and international activities we only knew vaguely about. We learned a lot about the influence Dr. DeBakey and Dr. (Antonio) Gotto had on the national scene in medicine. We learned that many of the innovations that came along in the '70s and '80s and '90s began right here in Methodist Hospital. We were interested in how much originality began here.

CM: Did you discovery any new figures in the Methodist or Medical Center history that maybe had been lost in time?

WW: I’ve been here so long I knew all the major players in the book. I knew just about everybody else who is in the book, except for those who were working here very early period in the hospital in the 1930s, but even some of those were still alive and working here when I came to Houston in 1968.

CM: So this was very personal history for you?

WW: It was, absolutely. I think that was another thing that prompted me to want to do this. There’s not many of us left. There’s only two or three of us around who go back far enough to remember all these people. It was important to get some of my own personal experiences down.

CM: After sifting through almost a hundred years of Houston heart history, has the past given you any particular insight on what we can expect in the future?

WW: I have this sense there have been such extraordinary changes and advances in cardiovascular medicine since the early 1950s, when my medical career began, that what takes place in the next 50 years is going to be just as extraordinary. There are things on the horizon, for instance in the field of stem cell research where we may be able to replace an aortic valve in the heart with a new valve grown from the patient’s own cells.

And nanotechnology the use of tiny mechanicals to use to introduce medications may play a big role. I just think the opportunities on the horizon are extraordinary.