Knee Jerk Anti Americanism or Six Flags?

The Smartest Guys on Broadway: Critics split on Enron

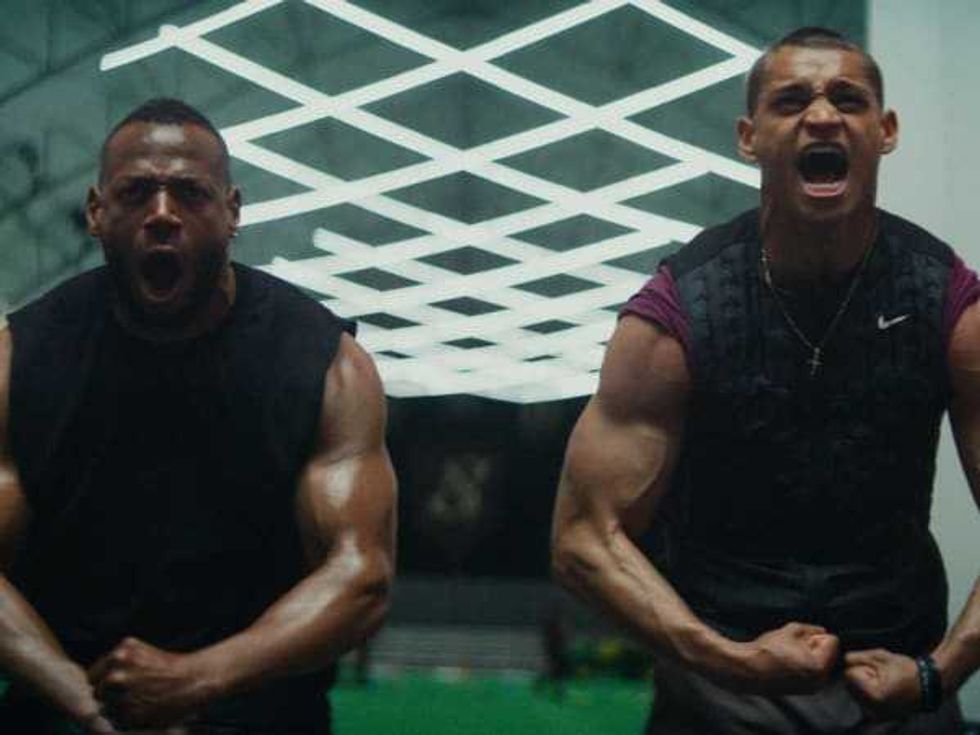

The cast of "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus

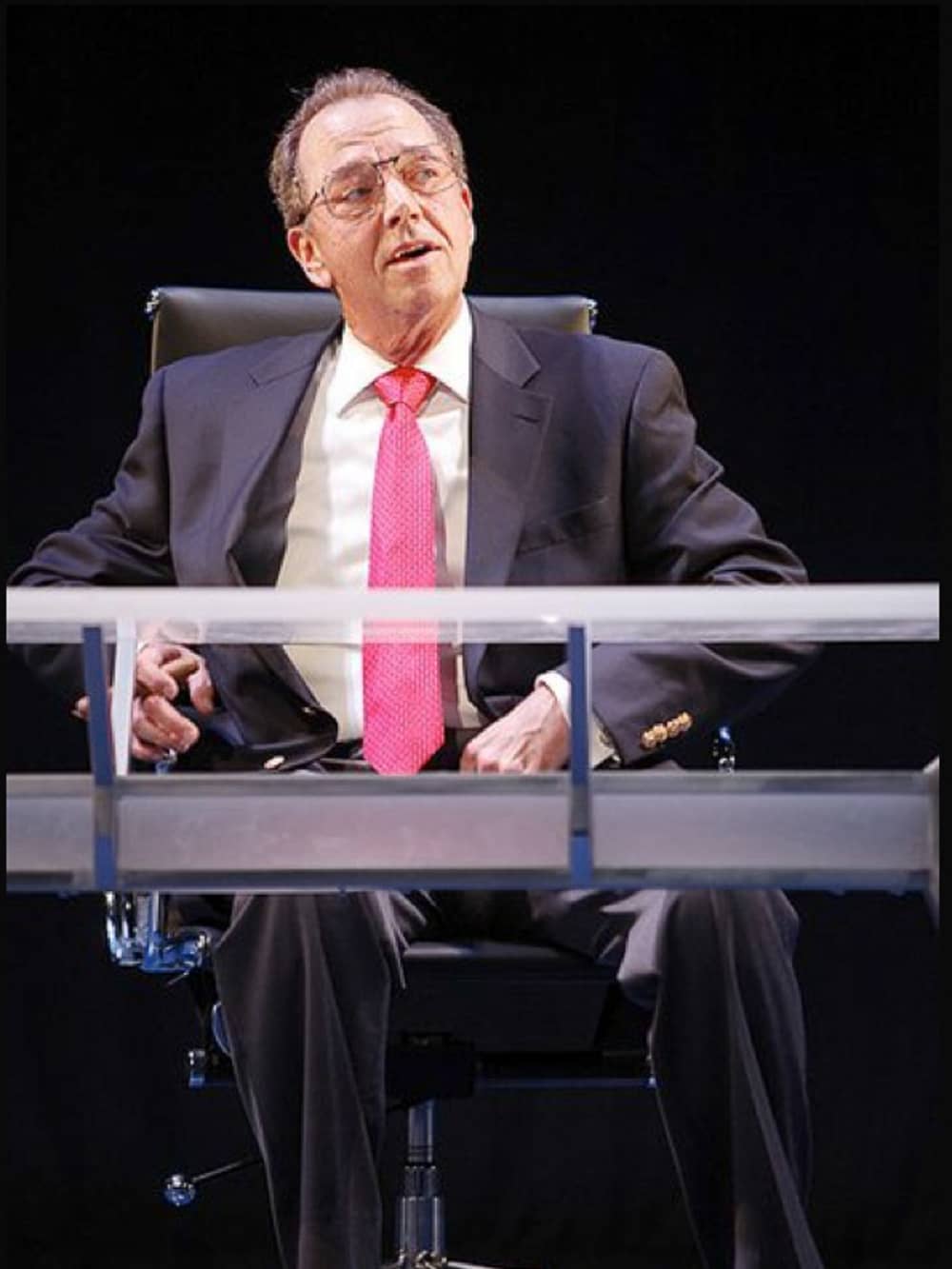

The cast of "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus Gregory Itzin as Kenneth LayPhoto by Joan Marcus

Gregory Itzin as Kenneth LayPhoto by Joan Marcus Stephen Kunken as Andy Fastow in "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus

Stephen Kunken as Andy Fastow in "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus Norbert Leo Butz as Jeffrey Skilling in "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus

Norbert Leo Butz as Jeffrey Skilling in "Enron"Photo by Joan Marcus

British playwright Lucy Prebble's bombastic musical take on the spectacular rise and fall of Houston's Enron debuted on Broadway last night at the Broadhurst Theater.

Critics have split on whether Prebble and director Rupert Goold's production makes solid entertainment out of the energy meltdown, or whether the show, like the company it skewers, is all flash and no substance.

Below, a roundup of what people are saying about Enron:

Ms. Prebble and Mr. Goold are a bit more literal-minded than Milton was. The play begins with three blind mice, in business suits, tapping their canes across the stage. Before the show is over you will have seen lawyers with kerchiefs over their eyes; accountants with ventriloquist’s dummies; and a little girl, the daughter of the Enron executive Jeffrey Skilling (Mr. Butz), surrounded by floating bubbles as Daddy frets over stock prices. When, toward the end, a character steps to the edge of the stage to announce that she has “the best metaphor” for “the values that define price,” your instinct is to cry out, “Please, not another metaphor!”

As the ever more obsessive Fastow, who becomes Enron’s chief financial officer, Mr. Kunken charts a slide into near dementia with wit and clarity. Granted, he has the great advantage of appearing with the show’s most inspired visual gimmick: a set of red-eyed, dinosaur-headed creatures called Raptors, the embodiment of Fastow’s debt-consuming substructures in a phantom company.

Come to think of it, it’s Fastow’s relationship with the Raptors, not Skilling, that is the show’s most fascinating. The vision of Fastow — a necktie wrapped around his head — and his raptors in his inner sanctum, just before Enron goes boom, brings to mind a war-warped, jungle-fevered character out of Apocalypse Now or The Deer Hunter. It’s a hilarious, scary image and one of the few in Enron that suggests the real heart of darkness meant to be beating at its center.

This British import, written by Lucy Prebble and directed by Rupert Goold, turns out to be one of the most vibrant new offerings on Broadway this season. It’s not that Prebble’s dramatic account is so illuminating — the documentary film Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room does a better job of filling us in on the tricks and tactics that led to what was by 2001 standards the largest corporate bankruptcy in the world.

But the synergy between Prebble’s play and Goold’s staging creates something that could only occur in the theater — a three-dimensional distillation of the greed, fraud and self-serving genius that spelled not just the demise of a company but the emergence of a form of casino capitalism that would by the decade’s end lead to the worst recession since the Great Depression.

This British import is partly a moral fable of human greed and partly a messy-but-juicy bit of theatrical schadenfreude, allowing us working stiffs (and armchair quarterbacks) to watch the retelling of how a group of pretentious suits hung themselves on their own wonkish derivatives. The suits, of course, had victims.

Enron won’t win any awards for stylistic unity, nor for subtlety. It comes with some of that irritating, knee-jerk anti-Americanism — especially anti-anything to do with Texas — that afflicts many left-leaning British writers essaying U.S. subjects from afar and invariably results in brash, crude, stereotypical cocktails of sex, excess and the rodeo. That can still play well in Manhattan, where the avaricious think themselves more subtle.

Still, this is an arrestingly timely show with some real intellectual juice running through its veins. It has every ounce of your attention. And thanks to Norbert Leo Butz — who clearly enjoys portraying Skilling’s semi-fictional transition from math nerd to, one Lasik surgery later, the studly king of the traders — the show has a dynamic and thrilling performance at its magnetic core. Butz blows Gregory Itzin’s Kenneth Lay and Stephen Kunken’s Fastow off the stage, but most accounts say that’s a pretty fair depiction of what actually happened at Enron.

After snoozing through many well-meaning tracts about Iraq, the prospect of a play about a financial meltdown wasn't appealing. But Enron is a whip-smart, edge-of-your-seat ride that'd rival anything at Six Flags -- there are even raptor-headed businessmen prancing around.

The playwright makes risk management as entertaining as pulp fiction, and the director isn't above visual puns. Enron created "joint energy development investments" (JEDI) in California, so he stages that state's blackouts as a lightsaber battle.

Goold doesn't let things stop moving here. And there certainly are a lot of intriguing, even outlandish things to see. Right from the start, we are treated to three blind mice, dressed in suits. A portent perhaps of the myopic view of a deceptively high-flying Enron by investors and Wall Street folks alike.

And we haven't even gotten to Scott Ambler's Jedi knight choreography (complete with lighted sabers) for the Enron staff or a set of obsequious Siamese twins representing Lehman Brothers anxious to get on the Enron gravy train.

Prebble's dialogue veers toward hyperbolic, big statements that eventually prove wearying, especially in the overlong and increasingly moralistic second act.

It makes you appreciate the show's visual moments. One of the more enjoyable aspects of Enron is being able to watch the perpetually moving electronic ticker tape of Enron's stock price — climbing higher and higher in Act 1 and then slipping lower and lower after intermission. Quite a ride. If only the play were as dramatically satisfying.