Art and history merge in many museums and galleries across Houston this month, as contemporary artists and curators look to the past for inspiration and examination. From Black History Month to agricultural history in the Americas to queer history to the mid 20th century glamorization of dining, we’ve got a range of shows for all art and history tastes. If that’s not enough, we get up close to Australian spiders and celebrate Houston as a town of makers.

"The Black Experience: Past, Present and Future” at Bisong Art Gallery (now through February 28)

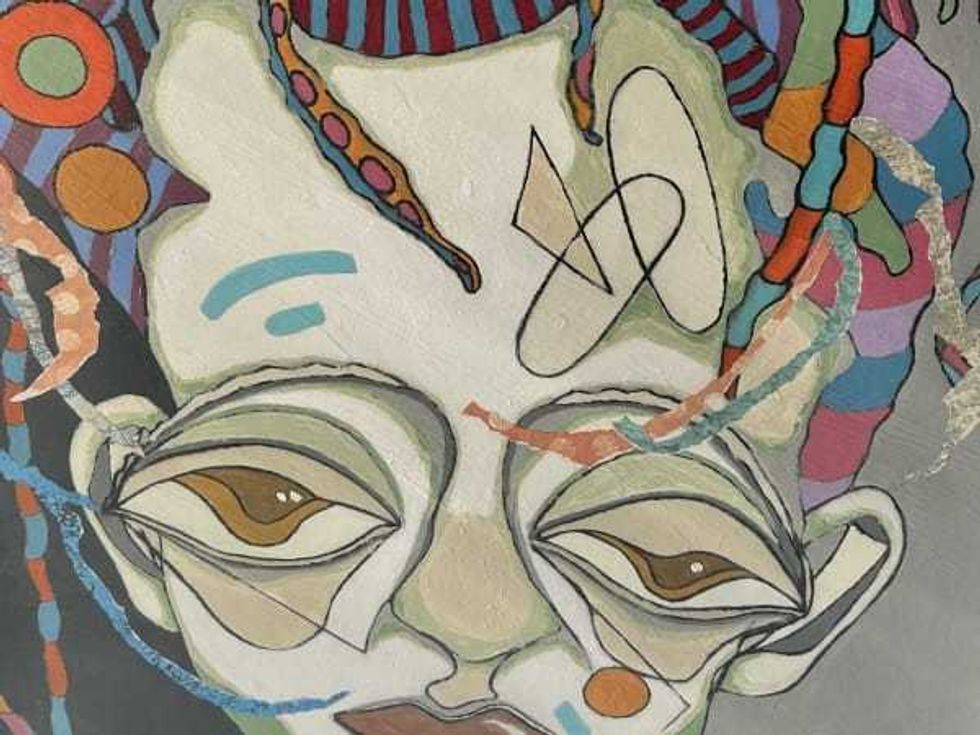

Celebrating Black History Month, Bisong Art Gallery presents this show curated by The Dream Affect Foundation. With a focus on Black artistic practice as both an archive and a catalyst, the exhibition features the work of six contemporary artists, including Lauren Luna, Romeo Robinson, Craig “TheArtist” Carter, Corey Haynes, Lanre Buraimoh, and John Whaley Jr. The gallery notes that these artists’ works reflect the enduring influence of history while asserting bold, forward-thinking visions of Black life, identity, and imagination. Though using a varied of medium and visual languages, what each artist has in common is an engagement with cultural memory, resilience, and creative sovereignty.

"Just Wood - Mostly” at Archway Gallery (now through March 5)

Featuring whimsical, creative, and utilitarian works “mostly” in wood, this new show showcases the quirky utilitarian and decorative sculptures by Robert L. Straight, as well as cabinet work by guest artists and furniture maker Tom Wells. From wooden race cars to body parts, Straight’s work offers many unique visions of what woodwork can be. Look for sculptures, new furniture, clocks, and sundry surprises from both artists.

“Nick Vaughan And Jake Margolin: Around The Corner And Two Blocks Down” at McClain Gallery (now through March 7)

The acclaimed Houston-based duo continues their multimedia 50 State Project to reveal lost queer histories and stories from across the U.S. This exhibition at McClain Gallery features some of the latest art from their wind drawing series, a selection of charcoal work within the larger project.

To explore ideas of history lost and rediscovered, the artists translate photographs of prior queer spaces into laser cut stencils and lay down charcoal powder onto the page. Then, they blow the charcoal away using pressurized air. The force of the wind drags the charcoal particulates across the tooth of the paper, etching the final image onto the page.

“Art, Place, and Power: Project Row Houses in Houston's Third Ward” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (now through November 8)

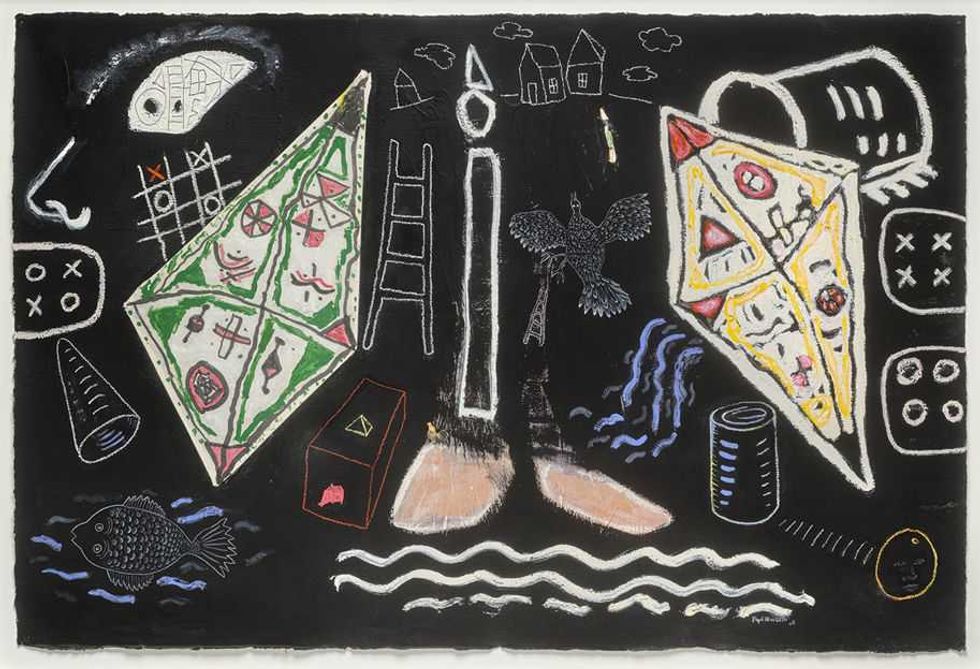

One great Houston arts institution celebrates the history of another great Houston art organization with this MFAH installation of works on paper by several of the founders of Project Row Houses, including James Bettison, Bert Long, Jr., Jesse Lott, Rick Lowe, and Floyd Newsum. In 1993, seven artists came together to transform a block of abandoned row houses in Houston’s Third Ward neighborhood, making them into a new kind of cultural space. As the Project Row Houses mission reminds us, the founders sought to preserve the culture and history in one of the city’s oldest Black neighborhoods through the practice of socially-engaged art.

For over three decades PRH has staged free exhibitions, offered artist residencies and youth programs, promoted the preservation of historic architecture, and become a cultural landmark in Houston. With this installation, the MFAH helps Houstonians gain further appreciation of the founders' art. These works celebrate the powerful impact of community-oriented artists and art.

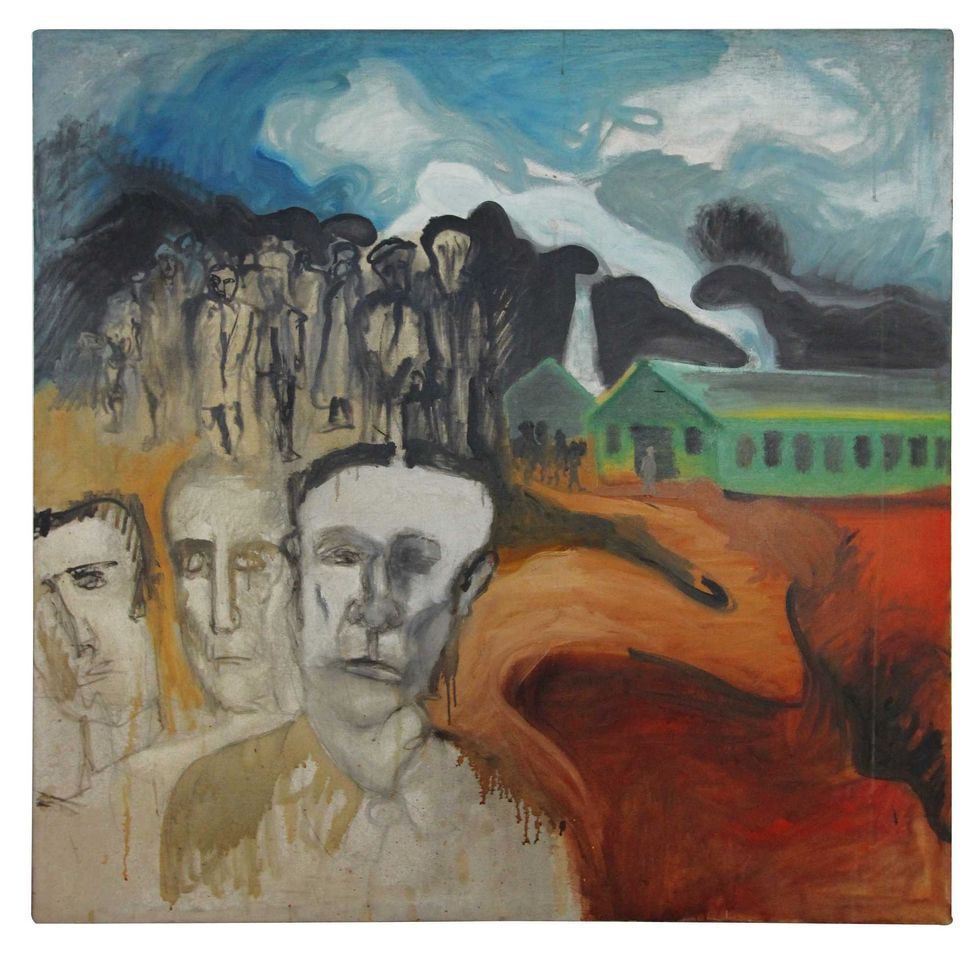

“Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try” at Holocaust Museum Houston (February 13-July 19)

For this exhibition focused on Boris Lurie, the acclaimed artist, writer, and Holocaust survivor, organizers use his artwork to trace the story of his remarkable life. Viewed together within the show, Lurie’s paintings, drawings and sculptures – many of which he never exhibited during his lifetime – create a portrait of an artist reckoning with devastating trauma, haunting memories, and a lifelong quest for freedom. The HMH notes that these works, presented along with objects from the artist's personal archive, trace his experience from his childhood in Riga through the concentration camps and postwar period in Europe, to his immigration to the United States, followed by his return visit to Riga thirty years after the Holocaust and beyond. Photographs, official documents, and personal writings underpin the visual retelling and processing of Lurie's survival and its crucial function in forming his identity as an artist.

“Midcentury Menu: Dining in the Atomic Age” at Rienzi (February 18-July 31)

The MFAH plates up a visually delicious dish of Midcentury Modern at Rienzi, the museum’s house for European decorative arts located in River Oaks. This unusual and fascinating exhibition draws from Rienzi’s historical cookbook collection and loans from the Heritage Society, to explore how convenience, technology, advertising, gender, and labor converged to redefine the meaning of eating in postwar World War II America.

The exhibition will examine how American’s perspective on food and dining changed at the end of WWII with waves of scientific advancement, complex supply chains, and the rise of popular culture media that put preparing meals, dining, and ads for modern appliances into magazines and on television. Cooks like Julia Child encouraged women to experiment with French cuisine, and the fictitious Betty Crocker championed convenience with step-by-step guidance. Food and home entertaining took center stage in this new age of abundance, and a wide range of cookbooks promoted everything from curious Jell-O salads to international cuisine.

“In Search of History” at Throughline Collective (February 20-March 21)

This juried exhibition and part of FotoFest Houston’s “Participating Space” program, examines the evolution of lens-based art. Curated by Museum of Fine Arts photography curator, Lisa Volpe, this show focuses on 21st century photography and especially the new uses of technology and the diversity in stories that technology brings.

“The works of art submitted to Throughline Collective demonstrate the wide-ranging vision of lens-based art,” Volpe said. “The artwork included in this exhibition provides a fascinating cross-section of artistic production, representing the diverse landscape of contemporary photography and also the vigorous involvement of the artists in contemporary discourse.”

“Maratus: Spiders of Paradise” at Sicardi Ayers Bacino (February 27-April 11)

This show of multi-disciplinary artist María Fernanda Cardoso’s work will feature her ongoing photographic project to bring the minuscule Australian Maratus spider into larger focus. Featuring large-scale and small-scale digital photographic portraits of various Maratus species, each photographic image is comprised of over 1000 individual photos. Seen together as one spider image, the photos reveal the spider’s colors and form and especially its unique and brightly colored abdomen that are part of the species’ elaborate mating rituals. Much of Cardoso’s work explores connections and tensions between society and the natural world.

“Mud + Corn + Stone + Blue” at Lawndale Art Center (February 28-May 2)

Last month, the Blaffer Museum opened the first section of this exhibition, organized by Blaffer chief curator Laura Augusta, that uses artwork to trace the historical entanglements between the United States and Central America through the angle of U.S. agricultural policy. Now Lawndale expands the selection of works from artists with ties to farming communities in the U.S., Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador. To complement the Houston presentation of this exhibition, Lawndale has commissioned a mural from Dario Bucheli, activations with Zine Fest Houston, and textiles and candies made by Jorge Galván. Lorena Molina will also install an outdoor corn maze in Lawndale’s 4900 Main Street lot as an immersive piece that explores the experience of immigration and diaspora.

“Clutch City Craft” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft (February 28-August 8)

Clutch City, Space City, Bayou City, now among our other favorite monikers for Houston, HCCC would like to add one more: Maker City. Calling H-Town “one of the nation’s most formidable centers of making” HCCC celebrations that maker spirit by organizing this special exhibition to examine Houston’s craft traditions and material cultures. The show features a wide spectrum of making practices, from the artists behind century-old, mosaic street signs to cowboy boot makers and fiber artists who design space suits and preserve the woven interiors of NASA mission control.

“Drawing its title from the city’s emblematic nickname — earned during the Houston Rockets’ back-to-back NBA championship wins in 1994 and 1995 — this exhibition uses Clutch City as both a cultural ethos and curatorial framework to examine how skilled craftsmanship underpins Houston’s industrial, social, and aesthetic identities,” HCCC Curator and Exhibition Director Sarah Darro said.

Image courtesy of Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino