The Review is In

HGO's rousing Nixon in China sheds new light on an American masterpiece

Chairman Mao Tse Tung wrote once that all of China's art and literature are "for the masses of the people," adding that "...they are created for the workers, peasants and soldiers and are for their use."

Their use? Translation vagaries aside, it seems like an odd choice of words. The quote appears in the opening pages of 1972 English edition, published in the People's Republic of China, of the score and libretto for the "modern revolutionary ballet" titled The Red Detachment of Women. Everything about this notorious Communist entertainment was apparently collective. No particular choreographer is listed in the book and no composer's name appears at the opening of the musical score.

What I find more striking, however, is the notion that a ballet, a parody of which figures prominently in the second act of Nixon in China, is something to be used. Here in the America, we usually think of such arts in terms of enjoyment. We want the arts to inspire and enlighten us, and hopefully to entertain us in the process. They are not often thought of as objects to be used, like flashlights or pot-holders.

I considered this all through the opening night of Houston Grand Opera's stellar Nixon in China. HGO had the foresight to commission this groundbreaking work in 1987, along with the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I saw it first in Brooklyn during the premiere run, and then a few years later in a more modest production at Boston Lyric Opera, and then again at the Metropolitan Opera in 2011, with the composer John Adams conducting.

It's no secret that I adore the opera and I continue to enjoy being perplexed by its deep structure and quirky contemporary aesthetic. Adam's music is constantly shimmering with some new idea, Alice Goodman's libretto is constantly surprising and eloquent, and each of the three acts offers myriad opportunities for interpretation and commentary. The opera is filled with gorgeous ensemble passages and the chorus as an entity is at the heart of the work. I have, I suppose, "used" Nixon in China for three decades as one of the finest examples of late 20th-century American opera.

Until this vivid production featuring Allen Moyer's set design and Wendall K. Harrington's video projections, however, I had not fully considered Nixon in China as an examination of the golden age of television. When Nixon sings "it's prime time in the U.S.A.," director James Robinson brings on an American nuclear family enjoying TV dinners on shaky aluminum trays. As the first act concludes and the chorus is shouting toasts, the family returns to enjoy Chinese takeout in paper cartons, complete with chopsticks.

Archetypal imagery is imbedded everywhere in this fascinating production, which is constantly reminding us that the various historical figures were well aware of themselves as players parading before cameras. In one of the many cultural echoes in this production, one of Andy Warhol's famous silkscreens of Chairman Mao appears on a wall of televisions. At times, the production feels as if it is being played out in the TV department at Best Buy. It's disturbing, it's often lyrical, it's ultimately mesmerizing. It's unlike any other grand opera production I've ever seen. Robert Ashley's Dust and Steve Reich's The Cave made great use of video, but those were not operas in the "grand" tradition.

Moyer's production has been presented by Canadian Opera Company, Opera Theatre of St. Louis, and Minnesota Opera, according to his website. While this is not a premiere for HGO, it seems that Sean Curran's choreography for the second act is new. His dancing demonstrates a very thoughtful fresh take, similar in intent to (but more subtle than) Mark Morris' self-consciously ironic ballet for the original production.

I do miss the pointe shoes, however. They served as an important common denominator with the regimental rifle-toting ballerinas of the original Red Detachment of Women. Evan Copeland and Kaitlyn Yiu make impressive appearances as the lead dancers, and Curran's choreographic organization provides a better route to Madam Mao's devastating aria, which ends in a kind of choral assault on the dancer who misses her "cue" to enter the cultural revolution.

Robert Spano confidently conducted the orchestra, which seems a bit smaller than the one I heard at the Metropolitan Opera six years ago, despite the saxophones. It's no matter, though, because both Spano and the musicians were clearly inspired by Adam's wildly rhythmic score and never wavered in energy.

Not minimal

Over the past three decades, some critics have ignorantly dismissed Nixon as a minimalist work. While Adams has acknowledged inspiration from operas such as Philip Glass' Satyagraha, there is little else about the work that makes it minimal. Adams has organized thousands upon thousands of notes in a rich orchestration, with clever references to many other styles, from American Big Band to Wagner's Tristan and Isolde. How is this in any way minimalist? I prefer to think of this opera as a post-modern, neo-romantic work with heroic qualities. The HGO orchestra, under Spano's baton, helped remind me of the grandness of the score.

There is a wide array of great singing in this cast, and no problems to report, except that the orchestra sometimes drowned some of the solo and ensemble singing. On opening night it seemed like the orchestra, soloists and chorus were still calibrating sound levels, perhaps in relation to the huge wooden set. Also it was announced that Tracy Dahl as Chiang Ch'ing was suffering from a head cold. Aside from a little hesitation at the outset of her famous second-act aria, though, I wouldn't have known it.

Patrick Carfizzi made me wish that Adams had given Kissinger a larger role; I continue to hold him in the highest esteem. Chad Shelton is nothing short of a brilliant helden-tenor. Holding court in the second part of the first act, probably the opera's most musically complicated scene, he made me hear aspects of the role I'd never noticed before.

High point of the opera

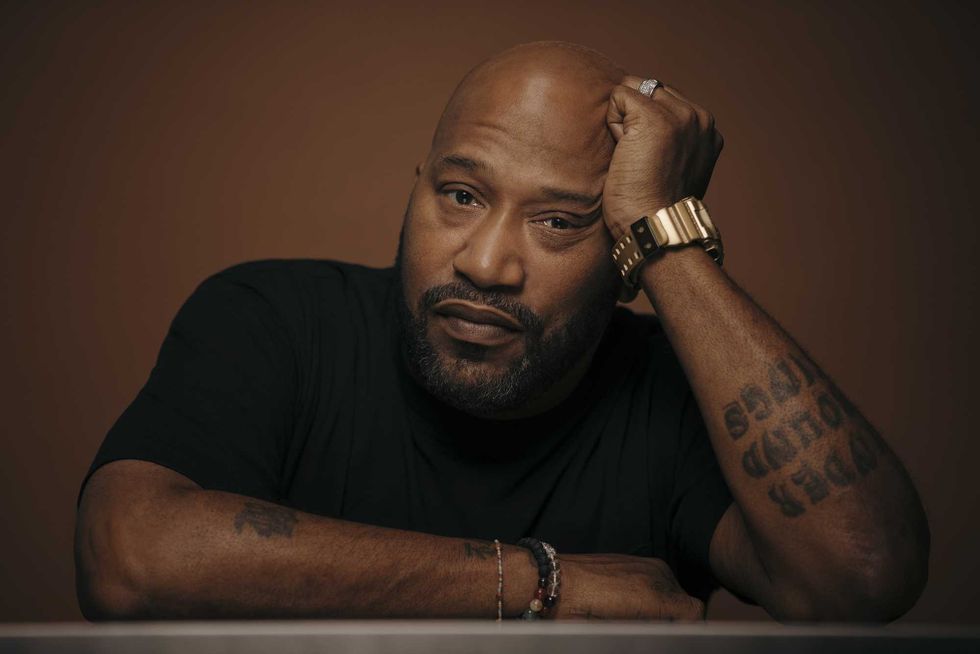

The high-point of the opera, however, in terms of arias (and this is an opera filled with well-defined arias) was Chen-Ye Yuan as Chou En-lai's toast. He is a baritone of great lyrical skill, seemingly in the early part of his career, but filled with great artistry. As the aria continues and he sings "we have at times been enemies," the passage accumulates extraordinary power. Chen-Ye cast a truly magical spell standing on a row of television sets, with layers of shadows dancing behind him as the toast unfolded.

This opera cannot fly without a great Nixon, and Scott Hendricks was a strong anchor, even if I had a hard time without James Maddalena in this famous role. Maddalena was the original Nixon, though his voice had faded somewhat by the time of the 2011 Metropolitan Opera performances. Hendricks needs to heighten his acting slightly if he is to command the necessary charisma in the part. He's a formidable dancer, however. Andriana Chuchman gave an elegant and polished performance as Pat Nixon, her clear and well-supported soprano voice soaring throughout the second act.

Moyer and Harrington's staging does a great deal to make the opera's third act, the weirdest and most unsustainable sector of the opera, really come to life. Peter Sellars' gray bedroom look for the original production, with young tango dancers floating behind a scrim, never really worked for me. The opera doesn't finish so much as it just fades away. I think the point is to make viewers fall into their own introspection. The language is fragmentary and puzzling.

As the scene progressed on opening night, I thought of the coincidence of watching it on the day of the presidential inauguration. The parallels were obvious, if not frightening. I thought about Mao's forceful propaganda and our current president's accusations of "fake news," just one of the many sad euphemisms will we are going to witness over the coming years. I wondered how future opera audiences might find a "use" for this great masterpiece. Where are the American operas for the "soldiers, peasants and workers?" Ruminations aside, one thing is clear: after 30 years, Nixon in China has clearly claimed its rightful place in the grand opera repertory.