The Arthropologist

Blood Memory exhibit at Holocaust Museum holds special significance in time oftragedy

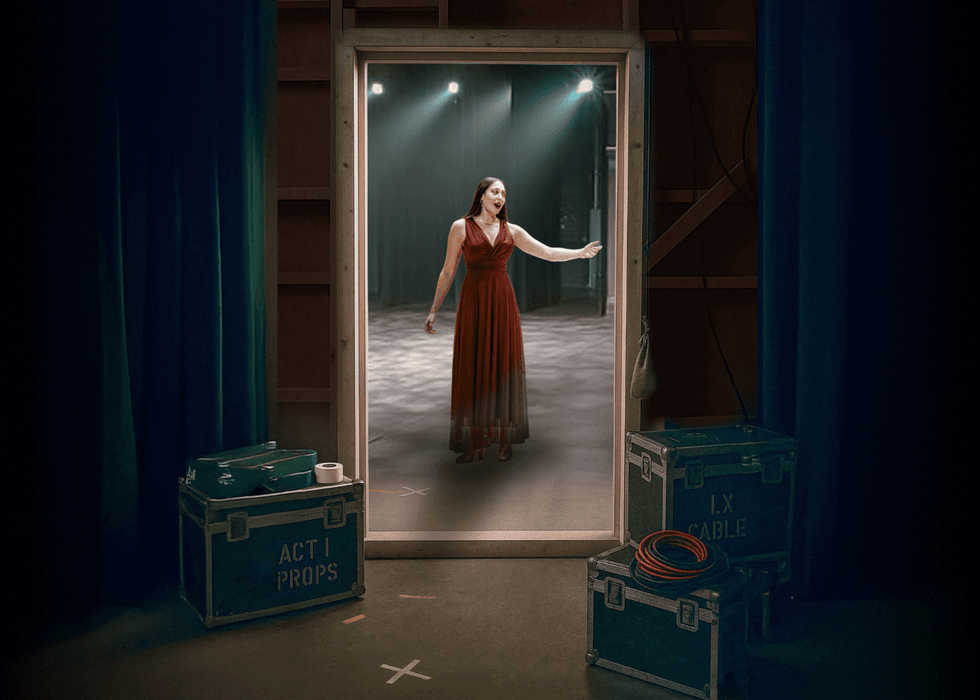

Lisa Rosowsky stands in front of Paris/Vel d'Hiv, a two-sided quilt, in herstudioPhoto by Paula Swift

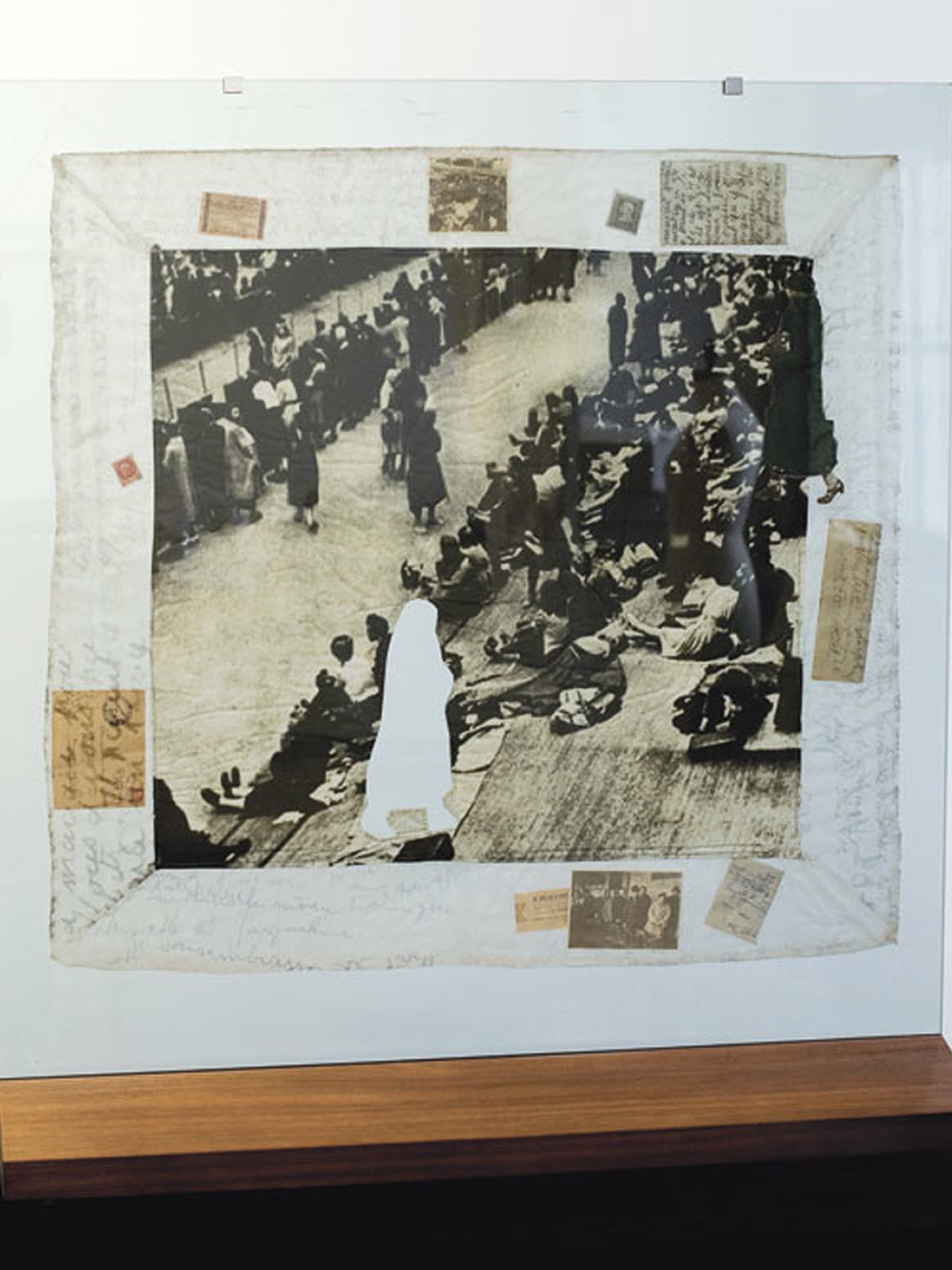

Lisa Rosowsky stands in front of Paris/Vel d'Hiv, a two-sided quilt, in herstudioPhoto by Paula Swift The other side of Paris/Vel d'HivPhoto courtesy of the artist

The other side of Paris/Vel d'HivPhoto courtesy of the artist Lisa Rosowsky, Designated Mourner, wool crepe, silk crepe, ribbed silk-linen,silk velvet, devoré silk velvet, and cotton, while the veil is digitally printedpolyester, 60 inches tallPhoto by Paula Swift

Lisa Rosowsky, Designated Mourner, wool crepe, silk crepe, ribbed silk-linen,silk velvet, devoré silk velvet, and cotton, while the veil is digitally printedpolyester, 60 inches tallPhoto by Paula Swift Lisa Rosowsky, Angel of Auschwitz, plaster, silk and barbed wire, body about 66inches tall, wingspan, 12 feetPhoto by Paula Swift

Lisa Rosowsky, Angel of Auschwitz, plaster, silk and barbed wire, body about 66inches tall, wingspan, 12 feetPhoto by Paula Swift

A nation was touched by President Obama's remarks on how we will honor the memory of the lives lost in Connecticut. Hopefully, there will be discussion, legislation, and as time goes on, art will commemorate the tragic event.

This week, I found solace in Lisa Rosowsky's astonishing exhibit Blood Memory: a view from the second generation, at Holocaust Museum Houston, a place dedicated to healing and memory, especially to the many children who died during the Holocaust. The healing was twofold: in the sheer elegance of Rosowsky's work, and the fact that at Blood Memory's heart is the story of a child, her father, who escaped to freedom.

Blood Memory, her first solo show, runs through March 24, 2013.

I found solace in Lisa Rosowsky's astonishing exhibit at Holocaust Museum Houston, a place dedicated to healing and memory.

Although Rosowsky is technically a first generation American on her father's side, in Holocaust lexicon, she is considered a second generation. Strolling through Rosowsky's spacious show in the Mincberg Gallery, I felt a palpable a communication between generations. And it wasn't easy.

Rosowsky grew up in a climate of silence about the past. I could see the artist telling a story she had to search for, piece together, quite literally with threads, as fabric is the central media. The entire experience is not so much dwelling in the past as coming to terms with one's history in the here and now. In Blood Memory, the blood is still very much liquid.

Rosowsky describes the concept of Blood Memory as “the knowledge that cannot possibly be handed down, but is, and it lies at the heart of my work as a visual artist.” Rosowsky employs a variety of media to tell her family's story, including textiles, quilting, sculpture, printmaking and installation.

Memory Meets History

During the great roundup of 1942, some 13,000 Parisian Jews were arrested and sent to Poland by train. Some managed to save their children by handing them over to non-Jewish friends, which is exactly what happened to Andre, Rosowsky's father, at the tender age of 5. He never saw his parents again.

He carried with him a collection of photographs that became one of the sources for Rosowsky's exhibition. When Andre was 10, he wrote down all his memories, a document that would land in his daughter's hands when she was in her twenties.

When Andre was 10, he wrote down all his memories, a document that would land in his daughter's hands when she was in her twenties.

It would be another two decades before Rosowsky sourced these materials into her art. The poignancy of Blood Memory speaks to a long internal brewing time. She sees her role in her family as the one designated to tell the story, a tale kept mostly silent in her family.

"In Holocaust literature, there is a term called 'memorial candle', the person who carries the memories," says Rosowsky, a graduate of Harvard College and Yale University who currently teaches at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. "I'm the memorial candle."

Her self portrait, The Designated Mourner, serves as a homage to her quest. A 19th century mourning dress contains a Kaddish memorial prayer in Hebrew on its skirt. As most Holocaust victims where left without families to carry out these rituals of mourning, Rosowsky takes up the mantle.

Angels and Life Jackets

The artist created the Angel of Auschwitz first, which anchors the exhibit, visually and psychologically. With barbed wire wings, the angel hovers over the space with a kind of urgent grace.

"I needed to get that out," recalls Rosowsky. "It was incredibly satisfying. The angel would tower over me while I was working."

"I love fabric, it's a wonderful medium. I have been sewing since I was 11. Fabric to me is what clay is to a potter."

The piece is both a gesture of healing and warning. "The Angel of Auschwitz ironically bears wings inscribed with a variation of the message on the welcoming gate of that concentration camp. Here, death replaces work in making you free. The shrouded figure beckons us, challenges us to pay attention," writes Eva Fogelman and Jean Bloch Rosensaft in their essay Art and the Transmission of Memory.

Fabric assumes the role of the dominating material. Here, even the stitching takes on a potent role. "It's a carrier of memory," Rosowsky says. "I love fabric, it's a wonderful medium. I have been sewing since I was 11. Fabric to me is what clay is to a potter. The translucent fabric feels close to memory."

I found myself moving slowly through the visual and tactile story, pausing in front of each piece to take it in. The artist has created a contemplative experience, allowing us to follow her own internal process.

Rosowsky's Life Jacket, a cotton and silk kimono with the words of of the great Tibetan spiritual leader, Thich Nhat Hanh, inscribed on the inside, assumes the role of an ending note.

"The piece celebrates life not despite, but because of, the frailty of our bodies: we are miraculous creatures. The way to honor those whom we lost 70 years ago is to appreciate the lives which we are privileged to live now," she writes in the work's description.

Closure and healing come together in the threads. "I definitely felt that when I had completed the jacket piece, I was closing some sort of door," she muses. "I even dared to hope that my fear of death would magically disappear once I had made the piece, but I guess that's too much to hope for, even from art."

A glimpse of Blood Memory