Mondo Cinema

Acclaimed movie Frances Ha is another labor of love for indie filmmaker Noah Baumbach

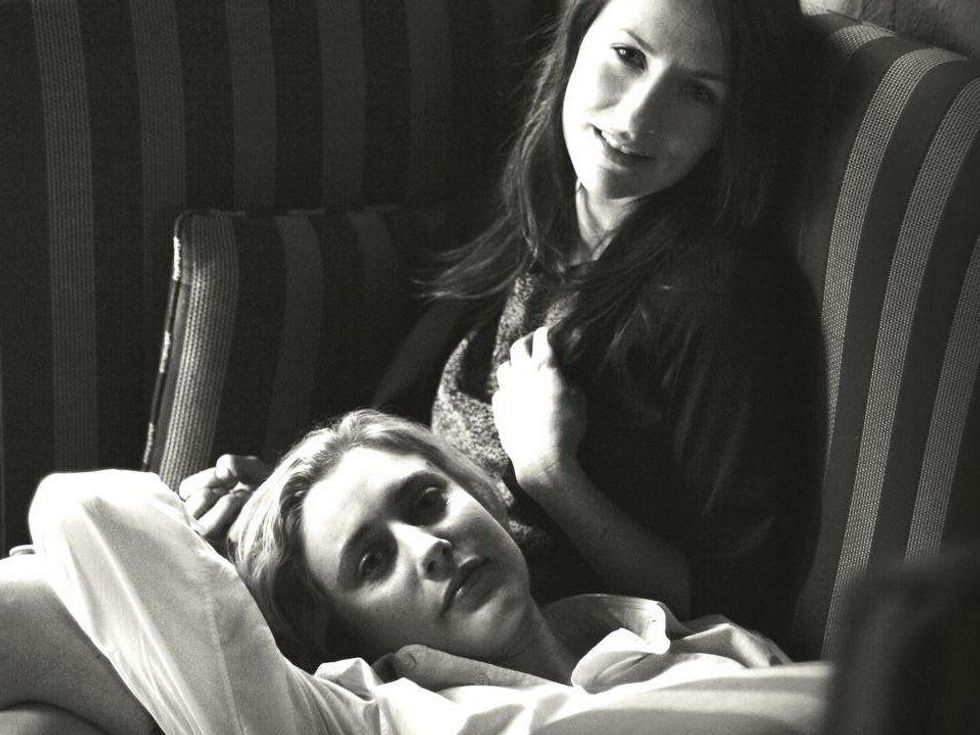

If Frances Ha (at the Sundance Cinemas) had not been filmed in relative secrecy – as The New York Times recently noted, few knew of its existence until its surprise premiere last fall at the Telluride Film Festival – you likely would have heard a lot of loose talk before and during its production about a marriage made in indie movie heaven.

After all, Greta Gerwig, who plays the title character and co-wrote the screenplay, had already established herself, while still in her 20s, as a mainstay of American independent cinema with movies as diverse as Hannah Takes the Stairs, The House of the Devil and Damsels in Distress.

And Noah Baumbach, the film’s director and Gerwig’s scriptwriting collaborator, was widely known and justly acclaimed for such notable indies as Kicking and Screaming, Mr. Jealousy, The Squid and the Whale and Margot at the Wedding.

They had previously worked together on Baumbach’s Greenberg, in which Gerwig appeared as an emotionally vulnerable woman involved with an impossibly needy neurotic (Ben Stiller). But Frances Ha is the project that solidified their partnership as artistic collaborators – and, ahem, very good off-camera friends – as they co-created what has turned out to be one of the year’s most highly acclaimed films.

Frances Ha quite obviously is a film by a filmmaker who loves New York, loves the French New Wave – and really, really likes (and respects) his leading lady and co-scriptwriter.

Gerwig plays Frances, a 27-year-old New Yorker who wants to establish herself as a dancer, remain best friends forever with her buddy Sophie (Mickey Sumner), and generally avoid ever having to acknowledge she can’t fulfill all her dreams. The movie takes an affectionate yet not uncritical view of Frances’ carefree rush through life – and gives the audience ample reason to have a rooting interest in her progress (or lack therefor) as she learns the hard way that growing up is hard to do.

Baumbach, the son of former New Yorker magazine film critic Georgia Brown, occasionally peppers his movies with in-jokey references to other movies. Indeed, in Mr. Jealousy, an unfaithful lover played by Eric Stoltz blows his alibi when he claims to have enjoyed a revival screening of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – and then describes the color cinematography of the black-and-white classic. (Busted!)

In Frances Ha, however, the references are less direct, more allusive, as he captures the ‘50s and ‘60s look and feel of works by Francis Truffaut and other French New Wave masters with the supple black-and-white cinematography of Sam Levy, and generous helpings of music by French film composer Georges Delerue.

Frances Ha quite obviously is a film by a filmmaker who loves New York, loves the French New Wave – and really, really likes (and respects) his leading lady and co-scriptwriter. We talked about all those things, and more, during a recent phone conversation.

CultureMap: Do you think it’s possible that, 20 or 30 years from now, we’ll see a movie in which an unfaithful lover gives himself away because he refers to Frances Ha as a Technicolor movie?

Noah Baumbach: [Laughs] Well, let’s hope so.

CM: I read somewhere that you’d been warned that shooting Frances Ha in black-and-white might diminish its commercial prospects by half. Is that true?

NB: Well, it’s not like somebody told me that specifically. And, really, I didn’t do any research into it before I started the movie, because I didn’t want to know. But as I understand it, it has to do with a lot of TV output deals that a lot of companies rely on to sort of cover their bottom lines. And if the movie’s in black and white, those deals often aren’t guaranteed – because the feeling is, black-and-white is not seen as something people necessarily want to see on television. And in Europe, there are some territories where they won’t show black-and-white. So while I don’t know that it cut the commercial prospects literally by half – it certainly didn’t help.

CM: But that didn’t stop you.

NB: I think I just felt like black-and-white was the right complement for the movie. I think that every story or idea that I am drawn to has some kind of look. It’s like I start to feel it, or see it, in a certain way. Sometimes it’s immediate, and sometimes it comes later. But in this case, it felt like it was right for the movie. I didn’t really articulate that to myself so much as I did when I felt, for example, that [The Squid and The Whale] should be done with a hand-held camera, or that Greenberg should be widescreen. It was just one of those visual ideas that come along and connect to the script as I’m writing it. Of course, I had been wanting to shoot a movie in black-and-white for a while. Greenberg didn’t feel like black and white. This one did.

I think I just felt like black-and-white was the right complement for the movie. I think that every story or idea that I am drawn to has some kind of look. It’s like I start to feel it, or see it, in a certain way.

CM: Seeing the black-and-white cinematography and hearing the Georges Delerue music, I kept expecting Frances would turn down a corner and run into Antoine Doinel from The 400 Blows. And I mean that as a compliment.

NB: I take it as one.

CM: There’s an interesting dichotomy at work in The 400 Blows. On one hand, it views adolescence as a time of boundless opportunities. But it’s also a time when controlling adults constantly limit your freedom. Wouldn’t you agree there’s something similar at work in Frances Ha? Frances is 27 and still ambitious – but she may be reaching a point where she’ll have to admit that some things just ain’t gonna happen.

NB: That’s an interesting observation. Because I think, yeah, in some ways, Frances does have to acknowledge that there are always some hurdles in your way – and there are some that you’re not going to be able to get over. And instead of running from them, you have to confront them.

Unlike in 400 Blows, for instance, when Antoine’s mom comes to visit him. There’s that shot that indicates his gaze goes up to her hat, or whatever, while she’s talking. And you know he’s just not listening to her anymore. When Frances is talking to Colleen, and Colleen offers her the job, Frances can’t hear it. She’s not listening anymore. She needs to learn that opportunities that are not, well, fantasies can actually be wonderful. And that roadblocks actually can be opportunities. I suppose that’s what she has to discover and uncover in this movie.

CM: You constantly hear about how much longer it takes these days for people in their 20s to invent themselves – to begin living the life they want to live. Do you think if you’d made Frances Ha 10 or 15 years ago, Frances might have been, well, younger than 27?

NB: That’s certainly very possible. I mean, for me, 27 was a big turning point emotionally. I didn’t know it at the time, but in retrospect, it was a big point of change for me. I was in the process of making my second movie, so I was in some ways doing well. But I think, essentially, I was going through what Frances is going through. Even if you’re right, from a sociological standpoint, that kids are sort of starting later, and remain tethered to home longer – which is all very possible – I still think that in terms of any kind whatever emotional and psychological development, 27 is a pretty big age.

CM: There’s a 14-year age difference between you and Greta Gerwig. In some ways, that difference is insignificant. But did you find that, because of your ages, you looked at Frances from different – if not opposing – perspectives?

NB: Well, something Greta said which I thought was interesting: She thought that, from my perspective, I could look at her more affectionately, more generously than she could. Because she’s more in that moment, and the sort of frustration of it, while I’m looking back at with affection for that time, and that person who’s struggling. I know that, at that age, it all feels so big to them – but I can look back and say, “Don’t worry, you’re going to be OK.”

Actually, I think one of the things that made it such a good collaboration is – well, obviously, she’s that age, and I’m not. I have my perspective, while she has a sort of more immediate take on things that made it very useful. But I think what really made it a good collaboration is that we were able to sort of swap those two. Greta’s wise beyond her years – and I’m immature, I guess. So we were able to look at things from both sides.

CM: Like some of your other movies, Frances Ha is a kinda-sorta love letter to New York. Do you think you could have set it anywhere else? In Los Angeles? In Houston?

NB: No. I don’t think I could have. I’m sure there are equivalent stories that other people could tell in those cities that I couldn’t. But the way I know the city and understand the city and look at the city – this had to be in New York. And going back to the photography: Doing it in black and white was a way for me to look at the city in a different way, so that it was both old and new to me again. I just have an emotional connection to the city.

I suppose the equivalent thing would be, I couldn’t have made this movie without Greta. That doesn’t mean some version of this movie couldn’t be made in Los Angeles with a different actor. But it wouldn’t have been made by me.

CM: A final question: Years ago, when I was interviewing Warren Beatty and Annette Bening for Bugsy, I joked with them that, someday, their kids would look at that movie and say, “Look! That’s the movie where mom and dad fell in love.” Do you think that you and Greta will someday look back at Frances Ha and say, “Well, that collaboration certainly turned out nicely.”

NB: [Laughs] I hadn’t thought of it like that. But I look at it even now as… well, we had a really good time making it. It’s one of those times when I feel like the joy of making it is evidenced in the experience of watching it. And I think that’s something you can’t even try to do. It just happens. So I think we will look back at this movie and feel good about it.

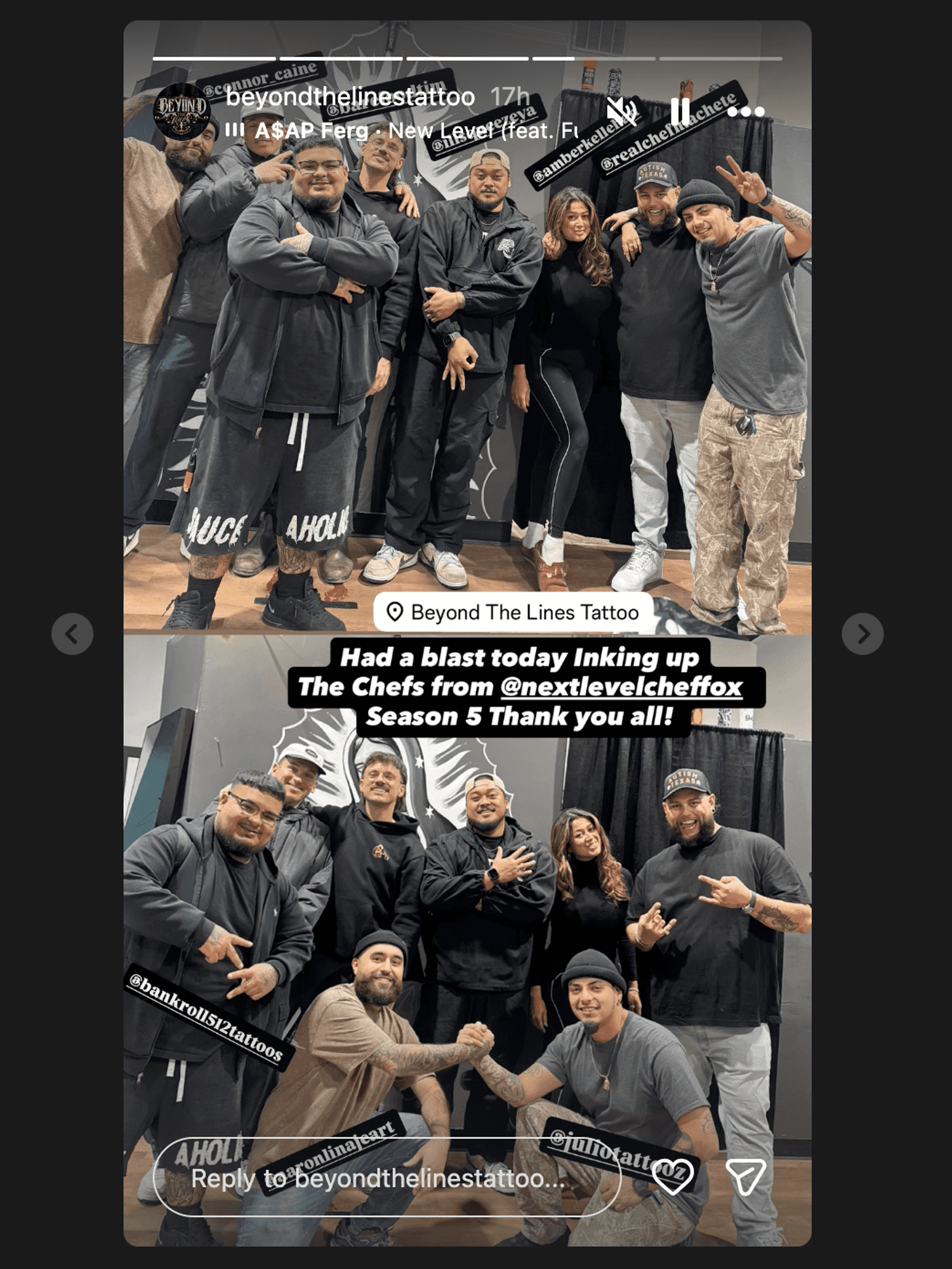

Looks like the chefs had a good time.

Looks like the chefs had a good time.