The CultureMap Interview

Writing and fighting: Author Andre Dubus III explores life as a Townie

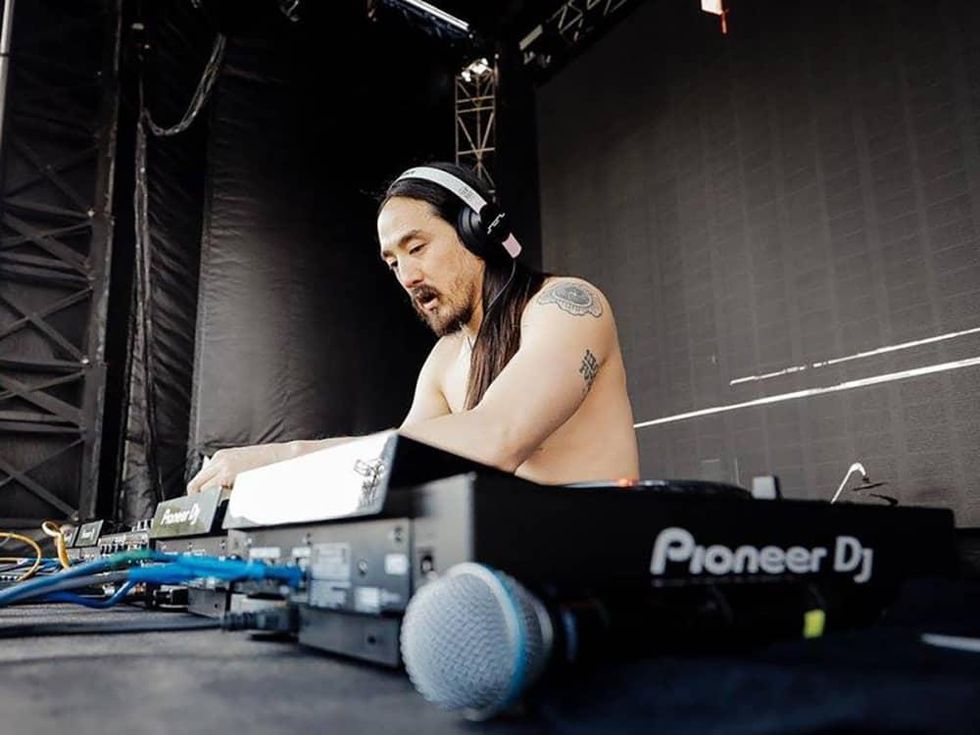

Novelist Andre Dubus III

Novelist Andre Dubus III "Townie"

"Townie" Brazos Bookstore

Brazos Bookstore

Andre Dubus III, best selling author of House of Sand and Fog and The Garden of Last Days and a National Book Award finalist, makes a Houston stop at Brazos Bookstore Tuesday on the book tour for his new memoir, Townie. In preparation for his Houston visit, he spoke to CultureMap about writing, memory, and what it’s like to act opposite Ben Kingsley.

To read Townie is to know the blood, muscle, and bone of the body. The book begins with a teenaged Andre, a child of divorce, making a 10-mile run with his acclaimed short story writer father, the co-owner of the name Andre Dubus. The young, novice runner wears his sister’s shoe, two sizes too small for him, since he has no sneakers of his own, and ends the run exhilarated, but with battered and bloody feet.

He writes: “I couldn’t remember ever feeling so good. About life. About me. About what else might lie ahead if you were just willing to take some pain, some punishment.” This statement seems to be the theme of Dubus’s life.

The memoir ends many years later, with his father’s burial, in a wooden coffin built by Andre and his brother Jeb, into a grave dug with pick and shovel by the brothers and a friend.

In between those experiences of running until his feet bleed and digging his father’s grave is a memoir that remains focused on the physical: on hunger when the family didn’t have enough money to make ends meet, on weight training, when young, skinny Andre is tired of being intimidated by the large men and boys who bully to survive the failing Massachusetts mill towns they live in. Above all it focuses on the fights — in parking lots, alleyways, boxing rings, and even an airport —Dubus gets into whenever he sees his family, friends, or even innocent strangers being intimidated and threatened the way he used to be.

Muscle and fists save his life on one occasion and get him thrown in jail the next.

Discovering the discipline of writing, of pushing pencil across paper to tell stories, saves his future.

I asked novelist Dubus if the writing process is different when writing of his own life, instead of an imagined one. He explains with fiction “you have to come up with everything ... you have to create the entire world. With memoir you’re off the hook with that. The events have happened and you’re trying to stay as loyal your memory of them as you can.”

The descriptions of his childhood self in Townie are just as vivid and detailed as the events of his adulthood. How does he maintain that solidity of memory? Dubus says it comes through the language.

“Working with the words brings me to the memories.” Using the metaphor of a therapist's questions, he says “The words will actually lead you back to these doors to your past and then the questions will get you to open those doors.”

He also believes “you have to be loyal to memory of the factual incident but you have to be more loyal to the emotional memory of that time.”

While the structure of Townie is linear, Dubus does play with time throughout the book. Several of the sections and chapters “begin in the middle,” in the immediacy of a new moment. Once thoroughly immersed in the new experience, he takes the reader back in time to explain how he got to that moment.

He says he uses this structure because “it reflects the nature of memory. We do kind of hop around. I do want to be loyal to the organic nature of memory with that structure. Also, I think it gives it more dramatic tension, to begin in motion and then circle back.”

Dubus believes this narrative technique might reflect something of his self. “I’m kind of that guy anyway. I throw myself into something and then figure it out as I go.”

I mentioned to Dubus that when Salman Rushdie was in Houston in December he spoke of working on his own memoir and the chance it gives him to answer some of the more frequently asked questions he receives so he can then tell everyone to “read the damn book” when asked again. I asked Dubus if there were any questions or topics, ones he is asked to speak on again and again, that Townie lets him put to rest.

He said while he tends to get many questions about growing up as Andre Dubus’s son, a “thorn in my side” that he has tried to let go over the years is that people think he grew up as a rich boy. “There’s nothing wrong with rich boys ... .but I’m not one and I never have been one.” Townie is a chance to correct some of people’s assumptions about his life and growing up with a writer father. He says that “feels good to get that off my chest.”

While Townie depicts Dubus the son, brother, weight lifter, boxer, bartender, University of Texas sociology student, correctional technician, carpenter and writer, one job that Dubus left out of the final drafts of Townie is stage actor. He started acting around the time he started writing, began “getting some nice attention,” and winning some lead roles.

At one point, he had a manager and was up for a movie role to play the brother of Eric Roberts’s character in a Dennis Hopper movie. Deep at work on a short story inspired by his parents’ breakup, he declined to be flown out for a screen test so he could keep focusing on that story, much to his manager’s disbelief. Writing would always win over acting because he says he can go years without acting and feel fine, but can’t go “two or three days without writing before I feel fucked up.”

He did later manage to win a small part in what would be a three-time Oscar nominated movie starring Ben Kingsley and Jennifer Connelly. That movie was the adaptation of his novel House of Sand and Fog. Writing the novel a movie is based upon proved to bring a few perks when he asked screenwriter/director Vadim Perelman to give him a part and pressed to be in a scene with Kingsley.

Dubus remembers: “I went and did the scene and I couldn’t believe I’m sitting across from frickin Gandhi.” Frickin Gandhi would earn an Academy Award nomination for his role. However, Dubus is a hilariously vicious critic when it comes to his own performance. He’s now mortified, claiming he’s guilty of eye overacting. He insists “I’m completely overacting with my eyeball.”

Perhaps the lessons he learned about being an eye ham he can put to use in his current project, a screenplay based on the material from a magazine article he wrote several years ago. Though he prefers the novel to screenplay form, his theater experience makes him want to write dialogue “that an actor can sink his teeth into.”

Dubus still writes the early drafts of his work with pencil and paper, and though he has three laptops and the Andre Dubus III website, he is concerned about what technology might be doing to writing and the novel. He has no problem with the current e-book format; however, he worries about how future technology might interrupt the experience of reading the novel, of the possibility of hyperlinks for definitions, ads, or chat rooms in the middle of an electronic book.

Dubus laughs and commands “Don’t have chat rooms. Don’t goddam have chat rooms in my book that I worked really hard to have you get lost in.”

He believes the novel will change, that all art forms are supposed to evolve. But he hopes it “doesn’t evolve beyond what I love about the novel, which is character driven stories. I just love reading about human beings in situations where they have to grapple with themselves.

"Hopefully that kind of novel’s never going anywhere because it’s a true reflection of the life we live."