The Review Is In

Houston Grand Opera's Marriage of Figaro doesn't need tricks: Sensual singingcarries the night

The Houston Grand Opera's take on the Marriage of Figaro centers on the power ofa young cast.

The Houston Grand Opera's take on the Marriage of Figaro centers on the power ofa young cast. The Marriage of Figaro could have been tragic. Instead it's dramatic.

The Marriage of Figaro could have been tragic. Instead it's dramatic. Anthony Freud says that Adriana Kucerová has a "white wine" voice.

Anthony Freud says that Adriana Kucerová has a "white wine" voice.

It’s difficult to imagine an opera more popular than Mozart’s gleaming The Marriage of Figaro, and perhaps the only downside to such popularity is a danger of exhaustion. For this reason, many opera companies around the world have sought to re-think the masterpiece for contemporary audiences. Peter Selllars’ version, set in the sumptuous surroundings of New York’s Trump Tower, comes immediately to mind.

Since Houston Grand Opera’s current season has featured shockingly innovative productions, it was surprising to enter the Brown Theater at The Wortham Friday night to see only Carl Friedrich Oberle’s faded 18th-century salon walls. Peeling paint and cracked plaster would certainly be the backdrop for a series of anachronisms, ironic metaphors and other witty displacements, no?

I prepared myself for zeppelins, mobile phones, maybe a few giraffes, all to no avail. You wouldn’t put a pink neon frame around Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, would you?

Well, that could work, but this wasn’t the night. During the four elegant acts I contemplated my operatic coming-of-age, which was centered in the post-modern aesthetic. Thirty years ago, it was spectacle that drew me to opera, and I am grateful to directors like Sellars and Robert Wilson for opening Pandora’s Box time and again. But there is a danger, sometimes, of forgetting the music itself. In the late 1970s, I remember seeing a production of Verdi’s Otello in which the singers did not even bother to act. They came on stage, sang their parts brilliantly, and then exited. I think, now, that I’m beginning to understand why.

HGO’s Figaro may be straightforward, but it is hardly sedate. It just doesn’t need a bag of tricks. The focus here is on the score, and on sublime yet understated ensemble singing. Sensual appeal is achieved as well through Michael James Clark’s vivid lighting design as the action progresses from morning to night. It’s just one “day of madness,’ as both the opera’s subtitle and Clark’s lighting plot remind us.

And what a paradox that a day of madness should unfold almost entirely in major keys! If there is a reason that an opera filled with seduction, revenge, deception and sexual aggression should still appear as a glass half-full, it’s possibly due to the sonorities. The whole of Figaro makes us laugh, even if the narrative is often deeply disturbing. “Susanna isn’t really going to have to sleep with that creepy old Count, is she?” is what you wonder while you’re nonetheless chuckling.

There is an evident youthful vigor here, starting with James Gaffigan’s consistently inspired conducting. From the first notes of the beloved overture, however, it was evident that he wasn’t trying to make the orchestra romantic or heavy handed. He allowed us to hear each line in Mozart’s score as if it were a perfectly polished piece of silver in a well-organized place setting. Special mention should be made as well of Bethany Self, who delivered an exacting Fortepiano accompaniment to carry the many recitativo sections along.

Adriana Kučerová, in her HGO debut, is a thrilling Susanna, the chambermaid at the heart of the action. She commands a warm, glowing voice that prevails in many arias and ensembles, really a miracle of sophistication and finesse.

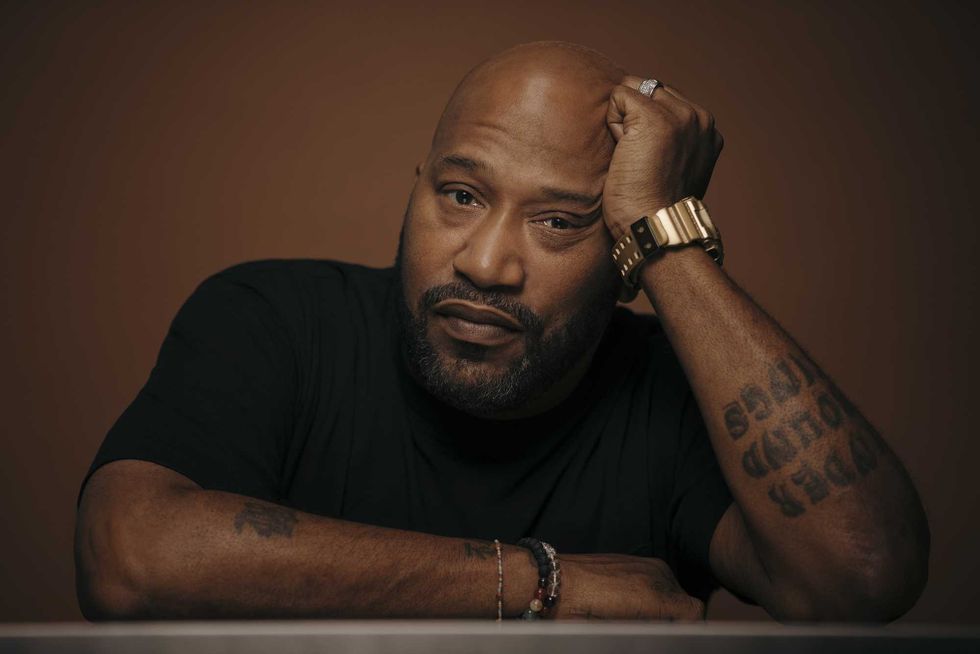

She is well-cast with Patrick Carfizzi (HGO fans will remember his stunning performance as Swallow in Peter Grimes), a Figaro who is simultaneously animated and confident. There has to be sex appeal in this part, and Carfizzi most certainly possesses it.

Ellie Dehn, also making her HGO debut, brought a kind of Hollywood glamour to Countess Almaviva, and Luca Pisaroni (another HGO debut) gives a definitive, vastly funny interpretation of Count Almaviva. Susanne Mentzer, several weeks after her delightful performance in Ravel’s l’heure espagnole with the Houston Symphony, offered an interpretation of Marcellina that was equal parts Kathy Griffin and Imogene Coca, in other words, simultaneously modern and classic.

Those who remember Michael Sumuel as the sexy cop in Dead Man Walking will love his boisterously comic performance here as the drunken Antonio, a brief, but challenging part, well-interpreted by this talented young singer.

It was an off-night for Marie Lenormand. Her Cherubino seemed to shrink away from this stellar cast like the new kid at school, and it’s hard to imagine why. When Kučerová egged her on to sing the celebrated “Voi, che sapete” to the Countess, I thought Lenormand might emerge from her shell, but she did not.

As Figaro proceeds, the ensemble passages grow from intimate duets and trios to rousing septets and octets, and mostly this Cherubino stayed safely in the background.