Serif embedded in swirls

Jill Moser's abstract prints and Charles Bernstein's poetics meet their match atWade Wilson Art

Jill Moser, "Hand in Glove," 2010

Jill Moser, "Hand in Glove," 2010 Jill Moser, "W6," monoprint on rice paper, 2010

Jill Moser, "W6," monoprint on rice paper, 2010 Jill Moser, "Lettres A-Z"

Jill Moser, "Lettres A-Z" "The Introvert"

"The Introvert" Jill Moser, "The Introvert"

Jill Moser, "The Introvert"

It's just past 9 p.m. in New York on Thursday, and artist Jill Moser is leaving a reading by poet Charles Bernstein at the Dia Art Foundation.

"I was just walking out and had to call," she says on the phone, almost shaken. "It was really incredible, given what's happened between us. In one of the poems he read, he had this line, 'Every color connected to a poem is proof of its inner life.' I felt like I needed to share that."

In worlds as hermetic as those of art and poetry, sometimes it takes an outsider to draw fruitful connections. Such is the case with the current exhibition at Wade Wilson Art, in which the enigmatic prints of Jill Moser have been melded with the writings of poet Charles Bernstein to create the book The Introvert, whose pages are on display through Jan. 4.

The collaboration arrived at the invitation of Gervais Jassaud of Collectif Generation (which counts University of Houston professor and former Art in America editor Raphael Rubinstein among its newest authors, collaborating with Blaffer-exhibited Amy Sillman). The French limited-edition publisher's vision involves juxtaposing contemporary artists and authors, resulting in "activated" books. Such a utopian meeting of image and word isn't frequently achieved. William Blake's illustrated poems are perhaps the most successful prior instance.

Jill Moser is a two-time vet of Wade Wilson's gallery, and Bernstein, the founder of poetry audio archive PennSound, has previously collaborated with artists Susan Bee, Mimi Gross and Richard Tuttle on books, paintings and sculptures. But the current show, Editions, is new terrain for the both of them.

"I've never made anything that's tactile," says the painter-printmaker. "Through the florescence and mineral colors, and the actions taking place on the page, I think I bring forth the vitality of the work."

Observing the pages on an exhibition-specific reading shelf that has been installed along the north wall of the gallery, the term "activated" certainly comes to mind. The interplay of Bernstein's clever wordsmithing ("If you Say Something, See Something"), letterpressed within Moser's confident strokes of dayglo hues and metallic whirls results in a book that's as irreverent as it is precious.

Moser, whose work is held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston agrees that her work and Bernstein's are a smart pairing. Her art isn't an illustration, nor is his text a caption. Although the artist was already familiar with Bernstein's work, the project was a bit of a blind date, as they'd never met.

"Our work shares a real sensibility," she explains. "The way he thinks of the movement he started, language poetry, as a super-genre that takes in linguistic files is similar to the way in which I use abstract figurations as a way of working. It's discursive of the whole history of working in painting."

She finds appealing the phenomenological approach Bernstein has to his poems; that is to say, the way in which the reader interacts with a poem.

"I too am interested in the way a viewer is engaged in a painting," she says. "That performative part is something we share."

The Introvert is a series of dichotomous flashes of light and dark, beginning with the book cover: Enthusiastic silver is dramatically scrawled around the front and back, but the horizontality of a highlighter-bright green line and vertical title on the spine makes the image grounded in an eerie manner. Like an introverted individual, the cover hints at the potential of the interior.

The collaborators teeter on detachment — Moser eschews direct application of her Pop palette in favor of dipping, blotting and squeegeeing, and fragments of Bernstein's lines are just as likely to fall off the page as they are to coalesce into a witty neologism.

"I use indexical marks in a kind of explicit and cloaked way, so you think you're seeing the artist's hand, but sometimes you're seeing the miming of the hand through a mechanical process," she explains, adding, "I think Bernstein does that with language. He plays with language, using words that have no relationship to each other except that they rhyme or have a shared rhetoric."

Yet some pages present disquieting imagery, in which Moser's strokes take on the form of taut, violent slashes and morbid blots, and the poetry reveals murmurs on mortality. The process unveils itself to the viewer, allowing one's eyes to travel over and under Bernstein's characters and Moser's calligraphic touch. Performative lines becomes form and words become meaning. With a mere turn of the page, the viewer catches blurred glimpses of these two iconoclasts as they lay themselves bare.

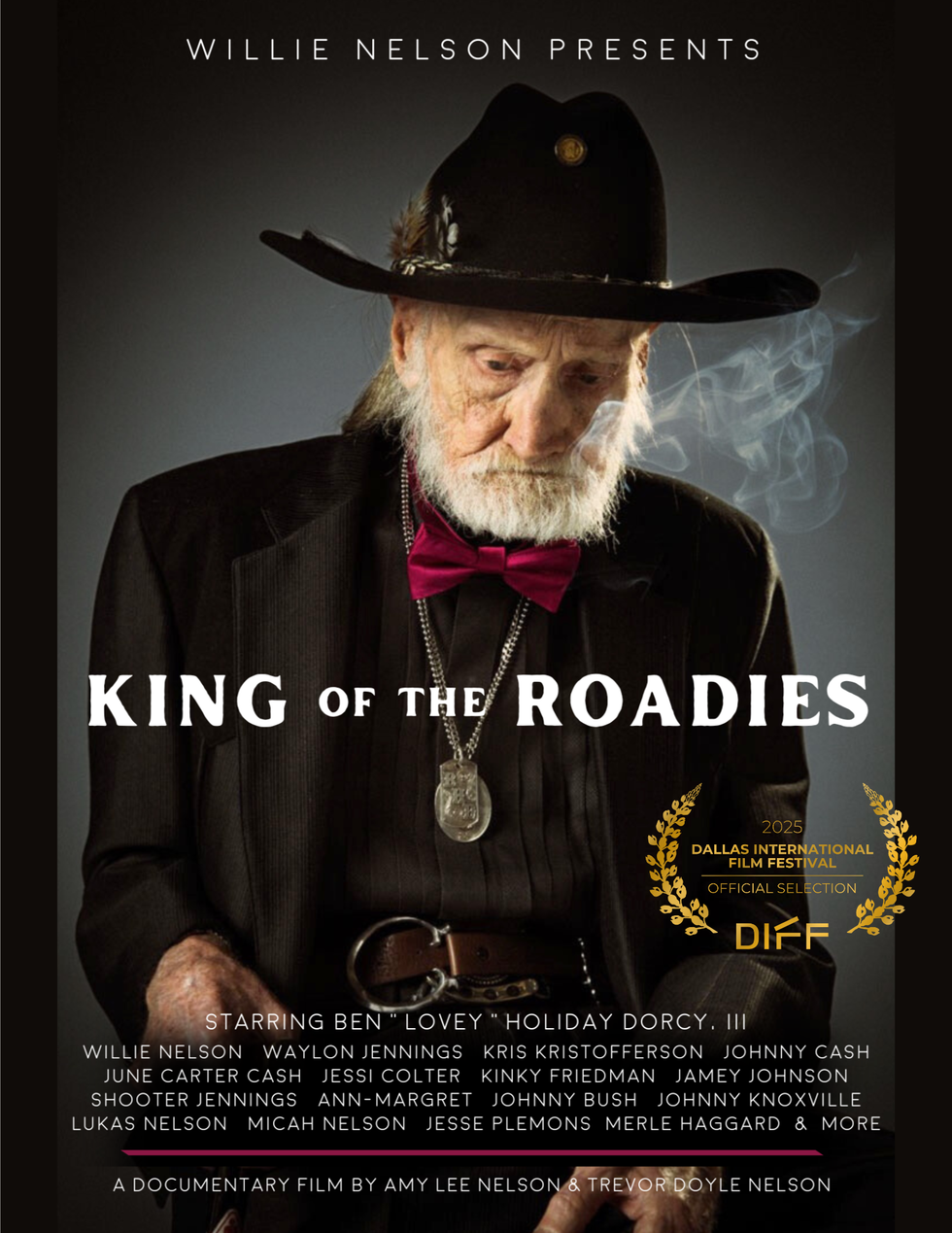

Film poster for Willie Nelson Presents: King of the Roadies at DIFFPhoto by Piper Ferguson

Film poster for Willie Nelson Presents: King of the Roadies at DIFFPhoto by Piper Ferguson