Popp Culture

Teddy Roosevelt & the bear: Worst. Valentine's Day. Ever.

With Valentine’s Day around the corner, I can’t help but think of PresidentTheodore Roosevelt, his association with those cuddly Teddy Bear toys andperhaps the most depressing Valentine’s Day story on record.

With Valentine’s Day around the corner, I can’t help but think of PresidentTheodore Roosevelt, his association with those cuddly Teddy Bear toys andperhaps the most depressing Valentine’s Day story on record. The political cartoon by Clifford Berryman titled “Drawing the Line inMississippi” that started the teddy bear phenomenon, according to DouglasBrinkley, Rice University professor, in his recent book, "The WildernessWarrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America"Cartoon by Clifford Berry

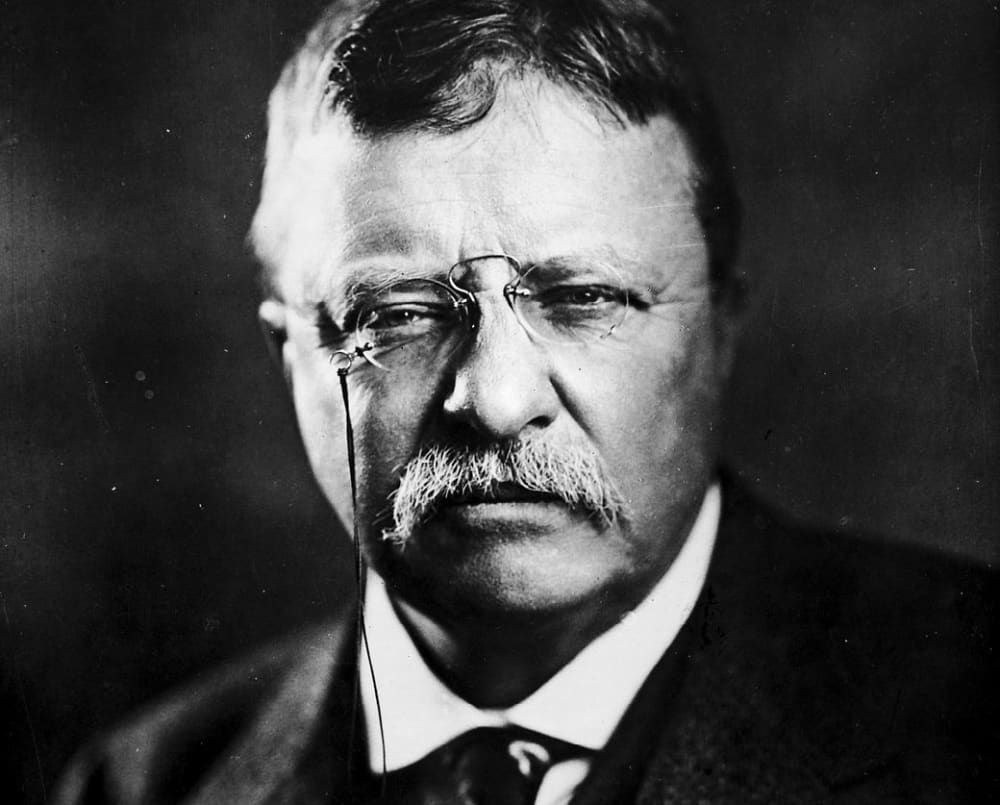

The political cartoon by Clifford Berryman titled “Drawing the Line inMississippi” that started the teddy bear phenomenon, according to DouglasBrinkley, Rice University professor, in his recent book, "The WildernessWarrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America"Cartoon by Clifford Berry Theodore Roosevelt, our 26th president, experienced probably the worstValentine's Day on record in 1884.

Theodore Roosevelt, our 26th president, experienced probably the worstValentine's Day on record in 1884.

I have an affliction: The innocuous and the enjoyable events in my life are often clouded by historical minutiae.

For instance, whenever the movie The Wizard of Oz comes on, I think about how some historians have asserted the movie is a parable for the Populist movement of the 1890s. Instead of the cute, but tormented, band of characters following Dorothy, I see a debate over currency policy in the Gilded Age.

Likewise, when I hear U2’s “Pride in the Name of Love,” I struggle to not correct Bono mid-song after he describes the “early morning” of April 4. With all due respect, I note, it was actually in the late afternoon “that shots rang out, in the Memphis sky.”

This is a malady that I’ve tried to shake, particularly for the sake of my friends and family.

And with Valentine’s Day around the corner, I can’t help but think of President Theodore Roosevelt, his association with those cuddly Teddy Bear toys and perhaps the most depressing Valentine’s Day story on record.

Quite romantic, don’t you think?

Teddy Roosevelt’s Bear

Teddy bears will, I’m sure, be given this upcoming Valentine’s Day as a token of love and affection. While I just can’t wrap my head around the “Build a Bear” concept, I realize that for millions these toys are adorable and cute.

Yet the history of the teddy bear is anything but cute and fuzzy. The Vermont Teddy Bear Co. can dress them up in any outfit they like, but I’ll still associate the toy with images of President Roosevelt in a swamp in Mississippi, a dead dog, a bloodied and dying bear and the guy who founded McIlhenny Tabasco.

I have a problem, I know.

Rice University Professor Douglas Brinkley provides a fascinating account of the history of the teddy bear in his recent biography on Roosevelt, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America. In this voluminous work, Brinkley describes not just how a bear hunt in Mississippi gave rise to the popular toy, but how Roosevelt became a founder of the conservation movement.

The Hunt

In 1902, Roosevelt journeyed south to address some political matters and to shoot a bear. An ardent naturalist, he loved studying and observing birds and animals. He was also an avid hunter and “enjoyed shooting the birds and animals he loved the most.” He was enthralled by the black bear, so hence the bear hunt.

A hunting party comprised of the grandfather of my favorite Civil War historian, Shelby Foote, and John McIlhenny, the Tabasco guy, accompanied Roosevelt. The hunt didn’t exactly go as planned. The party struggled for hours to find a bear, and when hunting dogs finally got on its scent, a nasty fight ensued. It didn’t go too well for either the bear or the dogs.

Brinkley describes the “gruesome scene.” When Roosevelt arrived, there was “a dog laying dead in the dirt, two others seriously hurt and a badly stunned, immobile bear tied to a tree, groaning for air.” The other hunters offered Roosevelt the opportunity to shoot the bear, but Roosevelt refused to shoot the wounded and vulnerable creature. Roosevelt believed such an act was not in the “sportsmen’s code.” So another one of the hunter’s killed the bear, with a knife actually, and the Washington Post reported the story of Roosevelt’s principled stand. Accompanying the article was a political cartoon by Clifford Berryman entitled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi,” and this, according to Brinkley, “started the ‘teddy bear’ phenomenon.”

In Brooklyn, upon seeing the cartoon and reading about the president’s refusal to kill the bear, Rose and Morris Michtom made two stuffed bears and asked for Roosevelt’s permission to market it. With Roosevelt’s assent, Brinkley documents that the teddy bear craze was started. By 1907, close to a million toy bears were produced.

Worst. Valentine’s Day. Ever.

Brinkley also recounts how Roosevelt experienced perhaps the worst Valentine’s Day on record. Prior to becoming president, and before going on that bloody hunt, both Roosevelt’s wife and mother passed away on Valentine’s Day 1884. They died in the same house, on the same day, just one floor apart.

Horrible, I know.

Roosevelt’s wife suffered from “Bright’s disease,” which Brinkley depicts in harrowing detail as “death by slow torture.” Just the day after she gave birth to a daughter, she passed away in the early afternoon of Valentine’s Day. Horrifically, just 12 hours earlier, Roosevelt had lost his mother to typhoid fever.

Roosevelt grimly recorded, “For joy or for sorrow my life has been lived out.”

But there is a glimmer of hope in this otherwise gloomy story. Brinkley illustrates in his book how Roosevelt’s life had not been “lived out.” Instead, Roosevelt immersed himself in his passion for the outdoors. As a result of his efforts, and his love for nature, he preserved for us all 230 million acres of federal park land and saved countless species of wildlife.

That’s a Valentine’s Day gift that keeps on giving.

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook