line up for this

2 new must-see Houston art shows draw up immersive, powerful experiences

It was artist Paul Klee who said that a “drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” In his mischievous statement, he evokes both the simplicity of the practice and the possibilities of where it can take both the artist and the viewer.

The process and the destination are of note, something that’s also central to The Menil Drawing Institute as it explores and studies modern and contemporary drawings to challenge conventions, definitions and assumptions of the medium's role in art and its opportunities and limitations—or lack thereof.

For many, drawing is subservient to painting, a stepping stone providing the fundamentals that make other mediums possible. Like the major and minor scales in classical music. Like the squat that makes a plié possible.

Two new exhibitions at the Menil Drawing Institute assemble works in which drawing holds its own as a medium with full expressive powers.

“Draw Like a Machine: Pop Art, 1952-1975”

It’s not hard to imagine that Andy Warhol wanted to “be a machine” and “machine-like” in how he made his art, a claim he made in a 1963 interview with Gene Swenson, New York editor of London-based magazine Art and Artists. Warhol’s rationale? Because “you do the same thing every time. You do it over and over again.”

It’s this sentiment that gave focus to the exhibition Draw Like a Machine: Pop Art, 1952-1975, curated by Menil Drawing Institute assistant curator Kelly Montana. Thirty-some works trace the inclusion of mass production, pop culture, advertising and commercialism in fine art. The show also include pieces by Al Hense, Lee Lozano, Leon Polk Smith and Marjorie Strider.

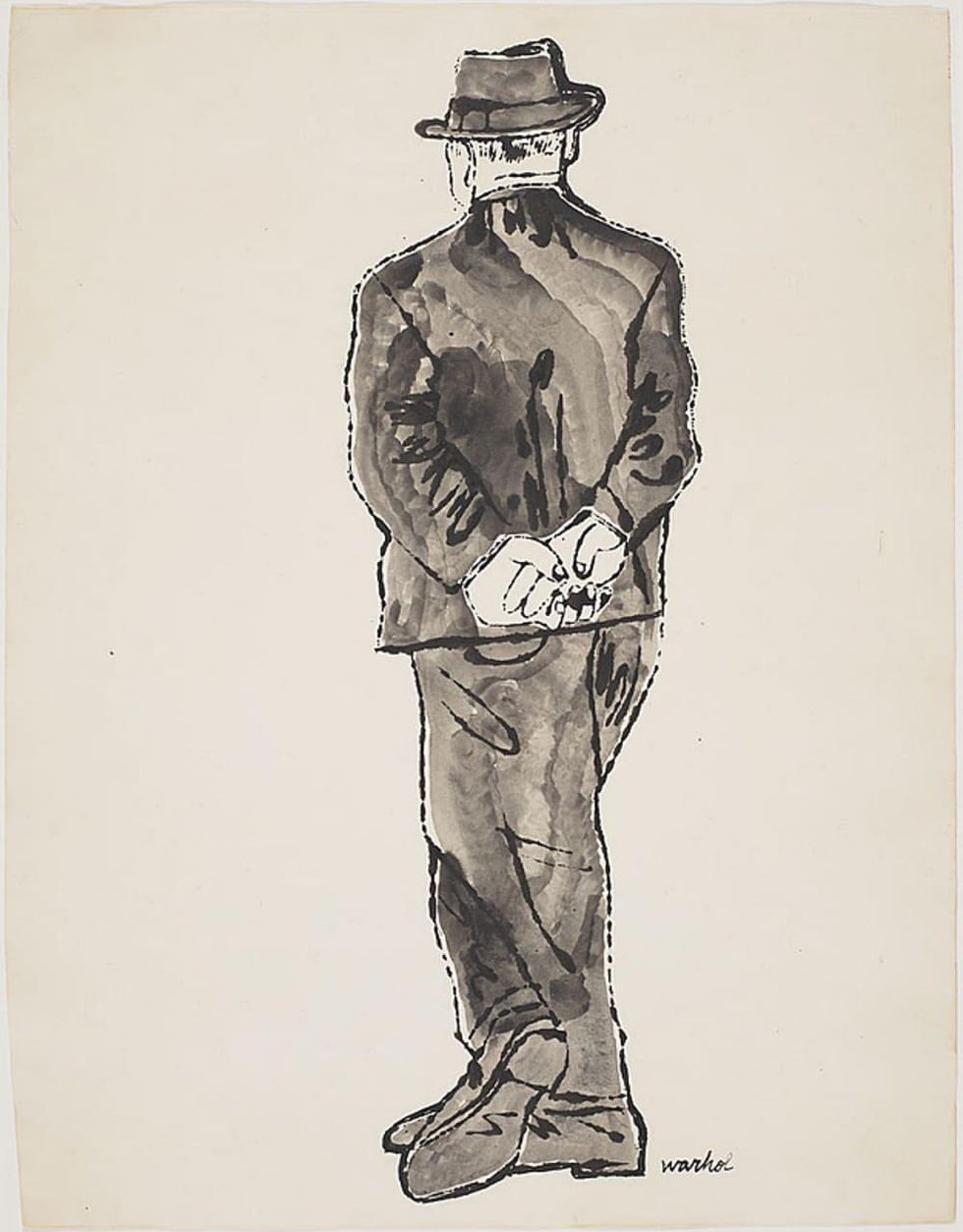

Montana explains that this artistic movement lessens the evidence of the hand in favor of mechanical production and reproduction processes in which the effects of machinery are part of the aesthetic. In Warhol’s Standing Man, circa 1952, there’s evidence of ink blotting that’s not meant as an accident. Rather, Warhol experiments with the outcome of the rendering mechanism as it becomes central to the accidental shading that ensues. The same focus is true in Cryssa’s The Stock Market, 1962, in which a newspaper typeset block of stock market data is repeated imperfectly to assemble a subtle, meditative pattern. The resultant gradients and variations come not from the artist’s hand directly onto the paper, but rather from objects meant to be used in commercial applications.

What comes to mind about this machine-versus-man tussle is the extension of the thematic thread to today’s digital mediums. Think of Facebook’s manmade algorithm that incites unpredictable engagement and outcomes outside the grasp of software developers. Or the rise of synthetic intelligence, in which data is used to render simulations that can be indistinguishable from reality.

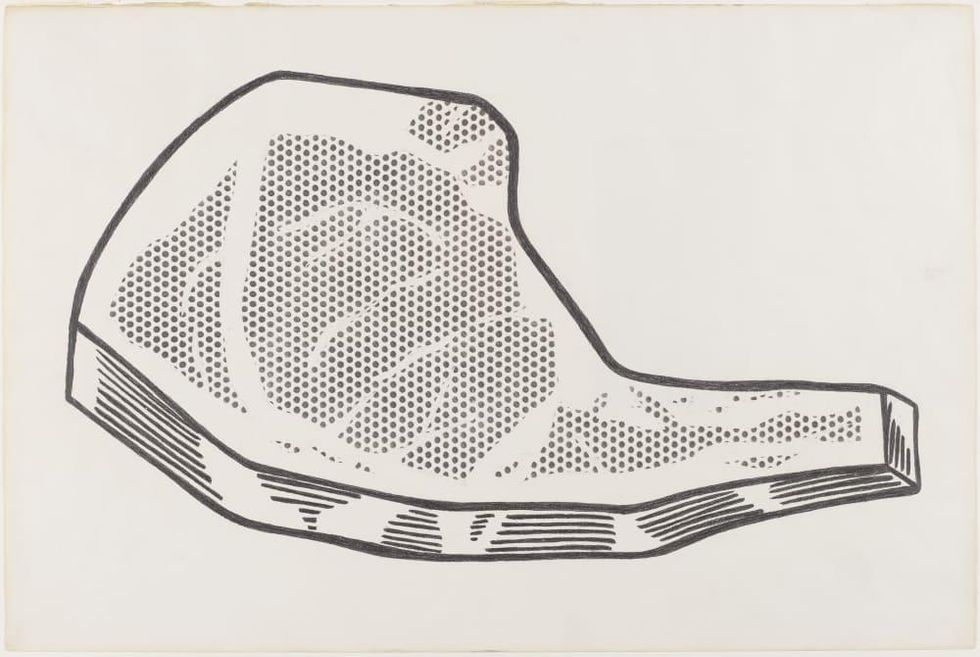

This comparison is fitting when considering works of Roy Lichtenstein, who once posited that pop art “doesn't look like a painting of something, it looks like the thing itself.” His Steak of 1963 evokes mechanical printing. In fact, the artist produced this piece by placing a perforated screen onto the paper and applying graphite and crayon.

“Spatial Awareness: Drawings from the Permanent Collection”

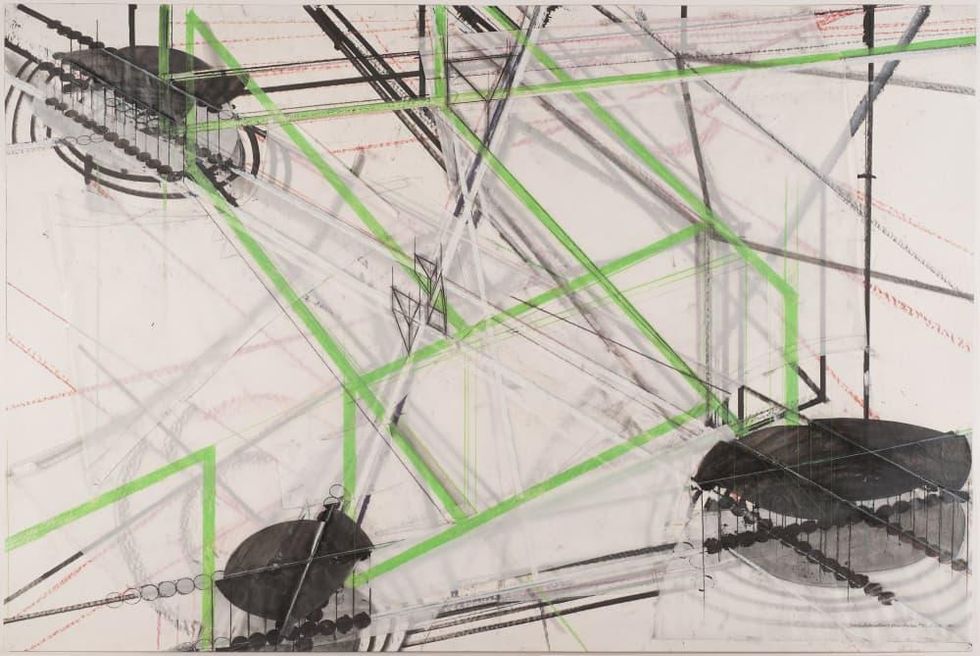

Try to follow along the orthogonal lines in Barry Le Va’s Drawing Interruptions Blocked Structures #4 and you’ll find yourself in a conundrum of perspectives that bewilders analytical minds. While the structure clearly portrays a physical space with a nod to industrialism, line groupings assemble illusions of space amid space—amid space. The eye doesn’t know where to go. Or are these lines depicting motion?

It’s hard to tell, but the exercise in trying to decide what’s what is a game with no beginning and no end. Yet somehow it’s still fun.

The 1981 work that welcomes visitors into the exhibition Spatial Awareness, curated by the Menil Drawing Institute’s first pre-doctoral fellow, Saskia Verlaan, introduces a rich dialogue that scores drawing’s role in transforming a two-dimensional medium into a three-dimensional experience. The collection of 30 works—including art by Sam Gilliam, Dorothea Rockburne, Trisha Brown, Richard Tuttle and Liliana Porter—is in the spirit of the institute’s raison d'être.

That’s fitting when considering that Le Va was primarily a sculptor and installation artist whose creative process often began with diagrams. He started with sketchbooks and moved into extremely large drawings that rivaled the scale of his installations. Upon his death in January, his tribute piece in New York Times compared them to scripts or musical scores.

Adjacent to Le Va’s puzzle is the 2017 work Untitled by Houston artist and Project Row Houses founder Rick Lowe. Here, a bird’s eye view of Houston’s Third Ward in which the Project Row Houses buildings stand out and serve as a geometrical, schematic foundation for the outline of a game of dominos, one of Lowe’s favorite pastimes. Verlaan explains that the layering of physical space and communal space expands how we might consider its definition in terms of the activation within it. In this case, it’s implied.

But in Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Two People (Due Persone), 1963-64, space isn’t implied, it’s delightfully dynamic. Two figures looking into a mirrored background place the visitor in the center of the work, also bringing the tangible surroundings into conversation with the piece. A reverse 20the century trompe-l'œil in which the two-dimensional work becomes three-dimensional? However you view it or play with it, it's a reminder not to take art too seriously.

Or that you’re a work of art, too.

---

“Draw Like a Machine: Pop Art, 1952-1975” and “Spatial Awareness: Drawings from the Permanent Collection” are on view at the Menil Drawing Institute through March 13, 2022. Admission is free.

In Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Two People, the visitor partakes in the completing the work, also bringing the tangible surroundings into conversation with the piece.