mamet's #metoo moment

David Mamet's provocative power play of he said, she said shakes up Heights theater

Don’t believe everything you’ve heard — or might hear — about Oleanna.

Still potent and provocative 26 years after its off-Broadway premiere, David Mamet’s live grenade of a drama about miscommunication and escalating power plays frequently recalls the oft-quoted observation of legendary Hollywood producer Robert Evans: “There are three sides to every story — yours, mine, and the truth. And no one is lying. Memories shared serve each differently.”

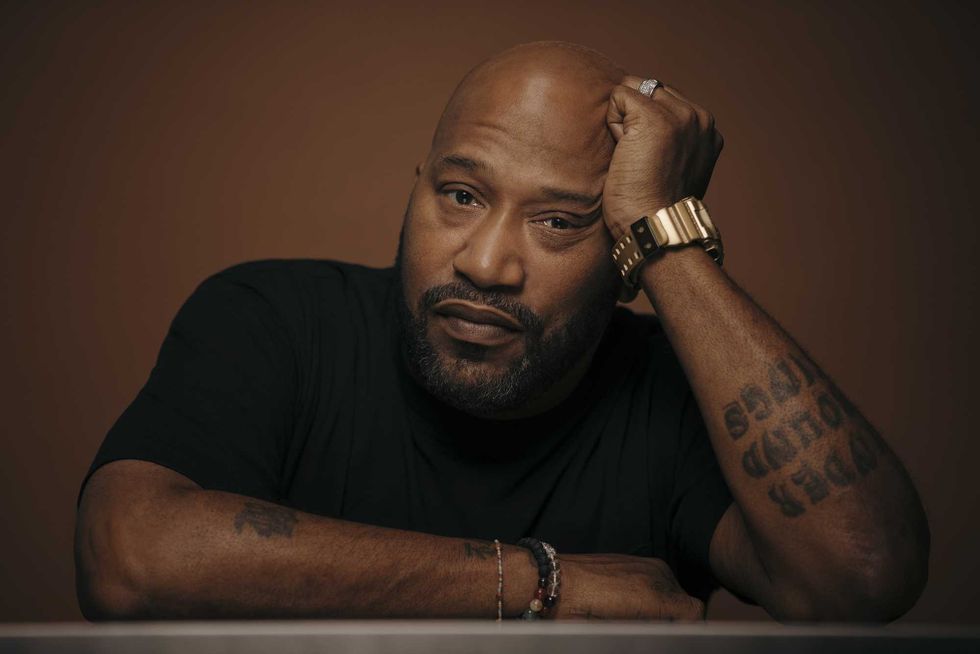

The complexities and contradictions of this tightly coiled two-character play are smartly illuminated by the exceptional Landing Theatre Company production on view at 14 Pews. And the lead performances by Marty Blair and Skyler Sinclair are so precisely and meticulously balanced by director Sophia Watt that some members of the audience might experience a bracing form of whiplash as their sympathies repeatedly shift while witnessing what can only be described as a war of words.

But keep in mind: Yes, it’s been frequently described — by critics, audiences, and even the advertising campaign for the 1994 movie adaptation directed by Mamet — as a drama “about” sexual harassment. It isn’t. Or, rather, it’s not just about that.

Things begin simply, ominously: While John (Blair), a self-absorbed college professor, is focusing his thoughts on purchasing a new house and pleasing a tenure committee, he takes far too long to notice the desperation of a student who has come to his office for guidance. Carol (Sinclair), a young woman charged by alternating currents of impatience and obsequiousness, fears she is “stupid” (her word, not his) and knows she is failing. She has tried very hard to grasp the finer points of John’s lectures, to fully understand the nuances of his textbook. But she just doesn’t get it. And if she can’t get it, she knows she will flunk out of college.

At first, John is too distracted to give her his full attention. And even when he begins to listen closely, he is too full of himself, even in his moments of self-deprecating humor, to avoid coming off as condescendingly paternalistic. She gets hysterical. He takes hold of her, briefly, to calm her down. She recoils. He offers to give her private tutorials. He says he “likes” her. They part company.

A few days later, it becomes very clear that each of them has a very different take on what occurred while they were alone together.

Act Two begins after Carol has filed an official grievance with the tenure committee, accusing John of sexual harassment. As proof, she cites his “pornographic” anecdotes. His offer to meet her again in private. And his attempt to embrace her.

John is flabbergasted, and more than a little frightened. Because of her complaint, he risks losing his new house, his tenure — and maybe even his job. He insists she has misinterpreted his words and deeds. But she will not be moved. Dogmatic and determined, she reports that, after consulting with her “group,” she has decided that John must make a public confession of his misdeeds as an elitist, a racist, a sexist, and a power-tripping authoritarian. One thing leads to another, lines are crossed, and Oleanna builds to a climax that is at once shocking and inevitable.

Back in 1994, when I visited the Boston location — ironically, a former mental hospital transformed into a faux university — where he was filming Oleanna, Mamet told me he was stunned by the intensity of the response to his play during its initial staging in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later off-Broadway. “People used to get into fistfights in the lobby,” he says. “And couples who came on a date would leave screaming at each other in different taxi cabs.”

What likely sparked many of those clashes, Mamet conceded, was the hot-button issue of sexual harassment. He had begun work on the play years earlier, set it aside — and then retrieved it from a file drawer in 1991 after Anita Hill delivered her accusatory testimony during the confirmation hearings for future Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas. In the wake of that nationally televised real-life drama, Mamet thought: “Wait a minute. I must be on to something here.”

And yet, Mamet quickly added, his completed play actually employs sexual harassment primarily as what Alfred Hitchcock used to call a “MacGuffin,'' a plot device that is introduced only to get the characters involved in something far more important. Like so many of his other plays — such as Glengarry Glen Ross, the one that netted him a Pulitzer Prize — Oleanna is all about power. Specifically, “It’s about people who have power, who think it's their God-given right,” Mamet says. “Who think that power makes them wise, and power makes their decisions correct, and people who dispute that are misguided. People who have power tend, even in their benignity, to be oppressive toward those who want equality.”

Director Sophia Watt agrees. For the most part.

“I can certainly see how the element of sexual harassment could be viewed as a MacGuffin,” she says during a recent interview. “I think in this current day and age, I was wary of completely discarding that as an element of the play, because I think sexual harassment fits very nicely into the dynamics of power. It’s, in many ways, an extension of someone exerting power over someone else.

“But I do think that, structurally, the play does not function if you make it entirely about sexual harassment. It’s not set up that way.”

Watt believes that — again, like many other Mamet plays — Oleanna deals with characters who use language as offensive and defensive weaponry, but at the same time often struggle to find language capable of expressing what they feel.

“This is particularly true in a university setting,” she says, “because I think in most cases, the student — Carol is obviously the exception — doesn’t feel like they have the ability to say ‘I’m uncomfortable, could we leave the door open?’ Or, ‘I’m uncomfortable, please don't touch me.’ Because that teacher has the power of their grade over them.

“I think it’s an interesting examination of what happens when someone comes forward and says, ‘I was uncomfortable.’ Do we have the language for that? I think we don't really yet, and certainly didn’t in ’92, to a full extent. So, that was something that interested me, too. In a play about language, how language failed these two characters, because I think it fails them again, and again, and again.”

And here’s the really tricky part: Carol repeatedly refers to a “group” consisting of peers, advisers and, presumably, legal counsel. These people — never seen, although their influence is keenly felt — have helped Carol find the words to express her rage and frustration. (“People always are noting how incredibly articulate someone can become when they get a lawyer,” Mamet pointedly remarked in 1994. “That way, you get someone to articulate your inchoate feelings.”) But are they the right words? Is it the precise language?

“Skylar Sinclair and I had a lot of discussions about that,” Watt says. “We wanted to walk a fine line, because to have her simply be kind of a puppet of this shadowy organization felt, in some ways, unfair to the character. She says these things, so we want to assume she has a certain amount of agency. At the same time, though, this is where I think we became really interested in where language fails people.” As Watt sees it, Carol told her confidants something on the order of, “I had this incident, and it made me really uncomfortable.” Trouble is, “The only way people know how to look at his actions toward her is through the lens of ‘Well, was it rape? Was it that level of assault, or was it not?’

“The language they give her doesn’t fit the event itself.” But what would be the right language? What really did happen? And should we assume that justice or something like it is served in the play’s final moments? To quote another noted playwright — Oscar Wilde, in The Importance of Being Earnest — “The truth is rarely pure, and never simple.” Watt fully expects audiences will consider those questions in polite discussions, or heated arguments, as they depart 14 Pews after the conclusion of Oleanna. So far, there have been no fistfights.

---

The Landing Theatre Company's production of David Mamet’s Oleanna runs at 14 Pews through August 11.