Not Favorites, Loves

Behind the art scenes: Gary Tinterow's own private MFAH is a place to save face

Gary TinterowPhoto via Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Gary TinterowPhoto via Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Edo, Benin Kingdom, Commemorative Head of a King, 16th–17th centuries, copperalloy (previous medium: bronze with iron eye inserts)Museum purchase with funds provided by the Alice Pratt Brown Museum Fund andgift of Oliver E. and Pamela F. Cobb

Edo, Benin Kingdom, Commemorative Head of a King, 16th–17th centuries, copperalloy (previous medium: bronze with iron eye inserts)Museum purchase with funds provided by the Alice Pratt Brown Museum Fund andgift of Oliver E. and Pamela F. Cobb Olmec, Seated Figure, 1500–300 B.C., ceramicGift of Mrs. Ralph S. O'Connor in honor of her cousins, Louisa Stude Sarofim andMike Stude

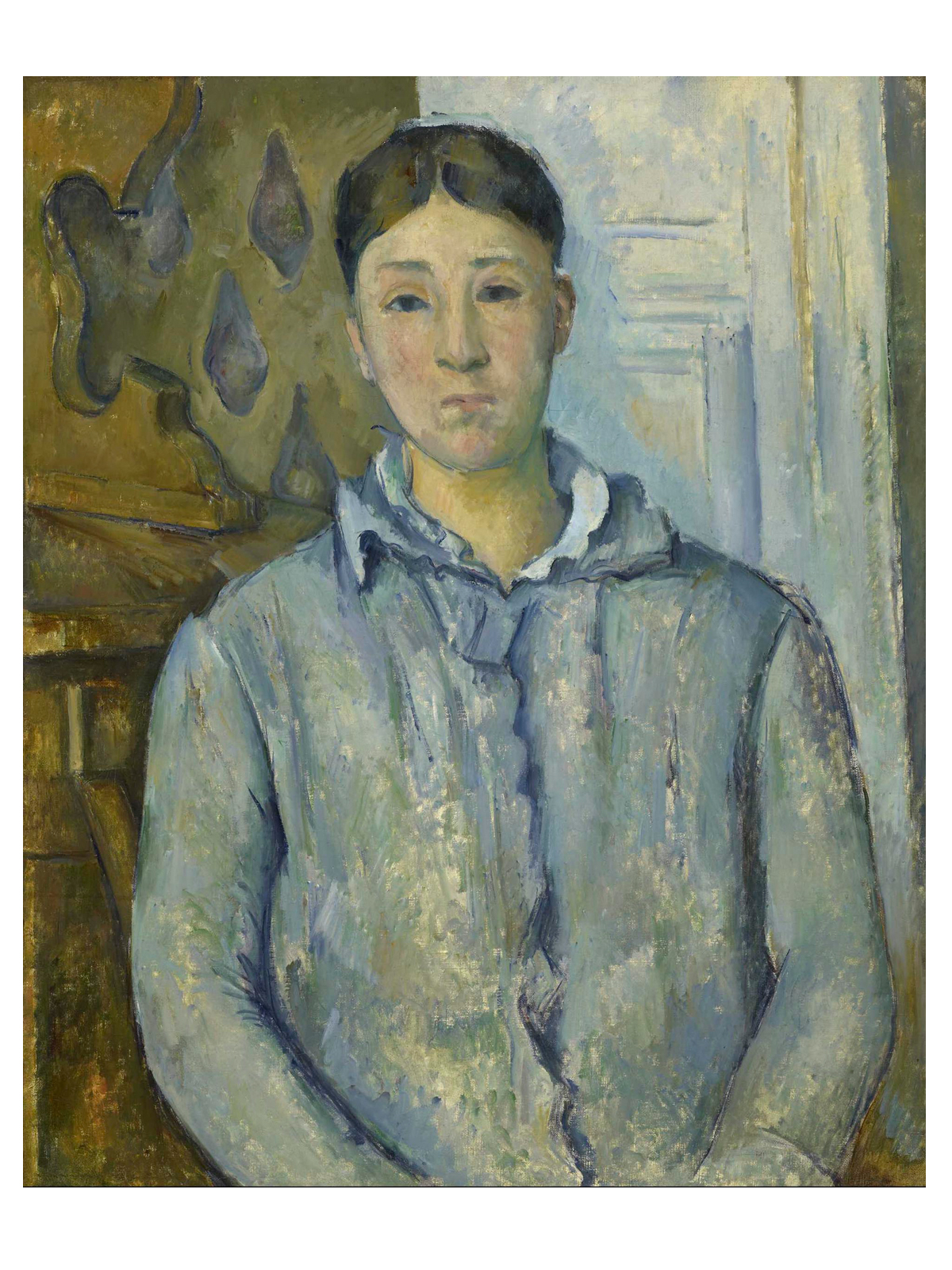

Olmec, Seated Figure, 1500–300 B.C., ceramicGift of Mrs. Ralph S. O'Connor in honor of her cousins, Louisa Stude Sarofim andMike Stude Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne in Blue, 1888–1890, oil on canvasThe Robert Lee Blaffer Memorial Collection; gift of Sarah Campbell Blaffer

Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne in Blue, 1888–1890, oil on canvasThe Robert Lee Blaffer Memorial Collection; gift of Sarah Campbell Blaffer Constantin Brancusi, A Muse, 1917, polished bronzeGift of Mrs. Herman Brown and Mrs. William Stamps Farish

Constantin Brancusi, A Muse, 1917, polished bronzeGift of Mrs. Herman Brown and Mrs. William Stamps Farish Rogier van der Weyden, Virgin and Child, after 1454, oil on wood

Rogier van der Weyden, Virgin and Child, after 1454, oil on wood Elie Nadelman, Tango, c. 1918-1924, cherry wood and gessoGift of Mr. and Mrs. Meredith Long

Elie Nadelman, Tango, c. 1918-1924, cherry wood and gessoGift of Mr. and Mrs. Meredith Long

There's nothing Gary Tinterow loves more than a good face.

So I learned behind the scenes at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston when the museum's recently minted director lead me in tow on a brisk walking tour through his new collection.

It wasn't faces I asked him about, however. It was favorites. As in "What are three or four of your favorite pieces at the MFAH?"

“Even at the Met, where I worked for 30 years," Tinterow said, "I didn’t have favorite objects. It’s like saying, 'Which is your favorite child?' "

I thought this would be a novel way of getting to know the museum's new director. But is there a more unfair question? Especially when there are nearly 64,000 to choose from and he's only been on the job a matter of months?

“Even at the Met, where I worked for 30 years," Tinterow admitted, "I didn’t have favorite objects. It’s like saying, 'Which is your favorite child?' "

A curator at heart, Tinterow created a startling selection to display the breadth of the collection, revealing something about his passions.

Those loves include faces but also brains. A brisk summary of Tinterow's philosophy from these selections might be this: Faces quicken the mind.

"Our brain is hard-wired to look to find a face on some elemental level — is it a mother, friend or foe, food or sustenance, or maybe sex," Tinterow explained. "We look at the face, we test it against our experience of faces and we begin to categorize: What’s the opportunity here?"

You might think first of portraits, but we began with a startling and compact Commemorative Head of a King, which dates from the 16th or 17th century and hails from Benin in West Africa.

“What I admire about this," Tinterow enthused, " is the impressive solidity of it, the direct engagement of this face with us."

But the underlying geometry of form is another central tenet in Tinterow's philosophy.

"It’s these circles of the necklace, the descending rods of the hair, those arc-like shapes for the eyes, lips, and nose. It amazes me," he said, "how the mind so willingly takes the information our eyes relay to our brains and makes this into an image of a person."

For Tinterow this leads to a preference for what he called "elemental simplicity." So I suspected we wouldn't be strolling towards anything Baroque.

"When works are overly elaborate, overly detailed and overly defined," he admitted, "there’s less for my brain to do and so I less powerfully engaged.”

Not far from the Benin sculpture, Tinterow spied his second choice.

“Let’s look at this wonderful Olmec laughing baby. Look how great he is!"

A product of the first major civilization in Mexico, this Olmec Seated Figure dates anywhere between 300 to 1500 B.C.E.

"That face is so particular, the asymmetry if it," Tinterow said, "and what is a very rare expression in art is a laugh, an open mouth, because it’s temporal. We only open our mouths for a little bit and it’s not thought to be timeless. A fleeting expression has been caught here.”

It may have been laughing, but I confessed to Tinterow I found it a little scary.

“There is something a little foreboding about it," Tinterow conceded, which reminded him of some of his earliest memories of art:

"Growing up in Houston, an object of great significance to me was this Olmec head that used to be here on the lawn. It’s now in Mexico City. It was a very powerful figure and I know that as a child that I was wary of that head. I was attracted to it, but it was also frightening."

He paused. "I also had a teddy bear I was frightened of."

"Is that here in the collection, too?" I asked. Sadly, his answer was, "No."

The Unfinished

Suddenly we were on the move again, passing from one building to the next and from early sculpture to modern painting. The next two works Tinterow paired were Paul Cézanne's Madame Cézanne in Blue and Constantin Brancusi's A Muse.

Clearly, the Cézanne is a favorite. "I find it a very affecting and moving picture," Tinterow said. "She’s lost in thought. What I love is this oval face, the vacant eyes, the mouth is just closed but not expressing a clear emotion."

Here emerged another aspect of Tinterow's interest: The unfinished. "What interests me most," he said, "is that it’s not finished. Cézanne understood that our mind was activated by the gaps of information. We are more engaged by the absence of things than by the presence of things."

Was even he allowed to handle one of the museum's great treasures? I thought alarm bells might go off.

An important part of Cézanne's story is also tactility and Tinterow returned to the fundamentals of perception to explain the allure of art. "The human body cannot function in the world just with the eyes alone," he said. "The early experience of touch is central to how we situate ourselves in space. By leaving the painting unfinished, Cézanne activated that sense of touch."

A slight stroll from Cézanne's unfinished portrait, was Brancusi's golden sculpture. "This work reminds me inordinately of Madame Cezanne," Tinterow said as we approached. "The geometric simplification, the indeterminate expression, and the fact that with very reduced and restricted means, Brancusi conveys almost as much information as Cezanne does."

Staring at this Brancusi one sees two faces actually, the coy suggestion of the sculpture's features and one's own face staring back in the golden reflection.

"A perfect end to the tour," I thought.

But we weren't over. Another brisk stroll and down to the lower level brought us to the preparation rooms to see the Rogier van der Weyden's haunting mid-15th century Flemish portrait Virgin and Child. Temporarily displaced for the upcoming "Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Gainsborough: The Treasures of Kenwood House, London" exhibition, the painting was sitting out on a cart.

I'm so conditioned by the policed nature of museum viewing that I nearly gasped when Tinterow picked it up and held it close so I could see it better. Was even he allowed to handle one of the museum's great treasures? I thought alarm bells might go off.

"I see this as Brancusi redux. Having seen Brancusi, I can’t helping thinking of it," Tinterow said. I was skeptical at first, but then I saw it too.

"When you look at the oval head," he continued, "the shapes are so similar. It’s that same impulse to find the underlying geometry and using that to great advantage to create an image of an object that engages the brain.”

He paused and marveled, "It’s one of the great greats.”

On For the Road

My tour over, I found myself reluctantly heading to my steamy car in the MFAH parking lot. Happily, I got a call a few days later from Tinterow, who just couldn't resist putting one more set of faces before me: Elie Nadelman's early 20th century sculpture Tango.

There were many of the same features — underlying geometry and a sense of the unfinished. And Nadelman, too, was interested in elemental forms.

"Where as many would have been interested in African art as a way of getting back to basics," Tinterow explained, "he found an American equivalent in folk art. Later, he embarked on a series of sculptures that engaged in elements he found in cigar store Indians or weather vanes or scrimshaw. Objects made by untrained but expressive artists."

Of course, these are dancers, so I found myself not so interested in the faces.

"What about the feet?" I asked, which seemed to merge into the pedestal beneath with the exception of the heel of the lady's back foot.

Tinterow said, quite simply, "It’s as if he wanted his figures to float.”