The Arthropologist

Artist Mark Fox manipulates text and blurs lines in If That Then This

One of the burdens of having spent a few decades studying human movement is being darn good at understanding the bodily evidence of just about everything. Wandering through the Mark Fox's exhibit If That Then This at Hiram Butler Gallery, I was struck by two things: Fox can make just about anything, and he probably had a life in the theater.

There was something about the way visual ideas traveled from medium to medium with an extraordinary versatility that told me a maker wonk was in the house. Houston art watchers may remember Fox's 2008 installation Dust at Rice Gallery, where he drew every object he owned. His current show at Hiram Butler runs though May 25.

Even the title, If That Then This, seemed to have a slyness to it. A drama was present in each work, a sense of movement, fragments of a narrative and an involvement with the spectator. I felt more like an audience member than a viewer. Now, it's also true that I often seem unable to drop my performing arts lens in looking at visual art. Still, Fox's work seemed to be informed by another life spent in a time-based art.

I was right on both counts. Fox had a background in puppetry and founded Saw Theater. The pieces started coming together — after all, aren't puppets really a form of animated sculpture? Although Fox has no plans to return to puppet theater as his work's focus, he is currently working on piece based on Toy (or Paper) Theater.

The pieces started coming together — after all, aren't puppets really a form of animated sculpture?

"These are tabletop sized stages traditionally used to recreate operas or popular plays in the home (late 18th, 19th century)," says Fox. "I love the form, and puppet theater in general, and always have the desire to create new works."

Painting actually led him into puppet theater and not the other way around. "I studied painting in graduate school. Before that I was making narrative paintings. I wanted to get back to the earlier narrative work but realized that the 'narrative' aspect of the paintings could be emphasized if the paintings moved," explains Fox.

"So I began to make paintings that had moving elements. Certain aspects of these paintings could be changed to further the narrative. These moving paintings then became puppets. With puppets, I became fascinated with the relationship between the puppet/object and artist/manipulator."

Performance art turns visual

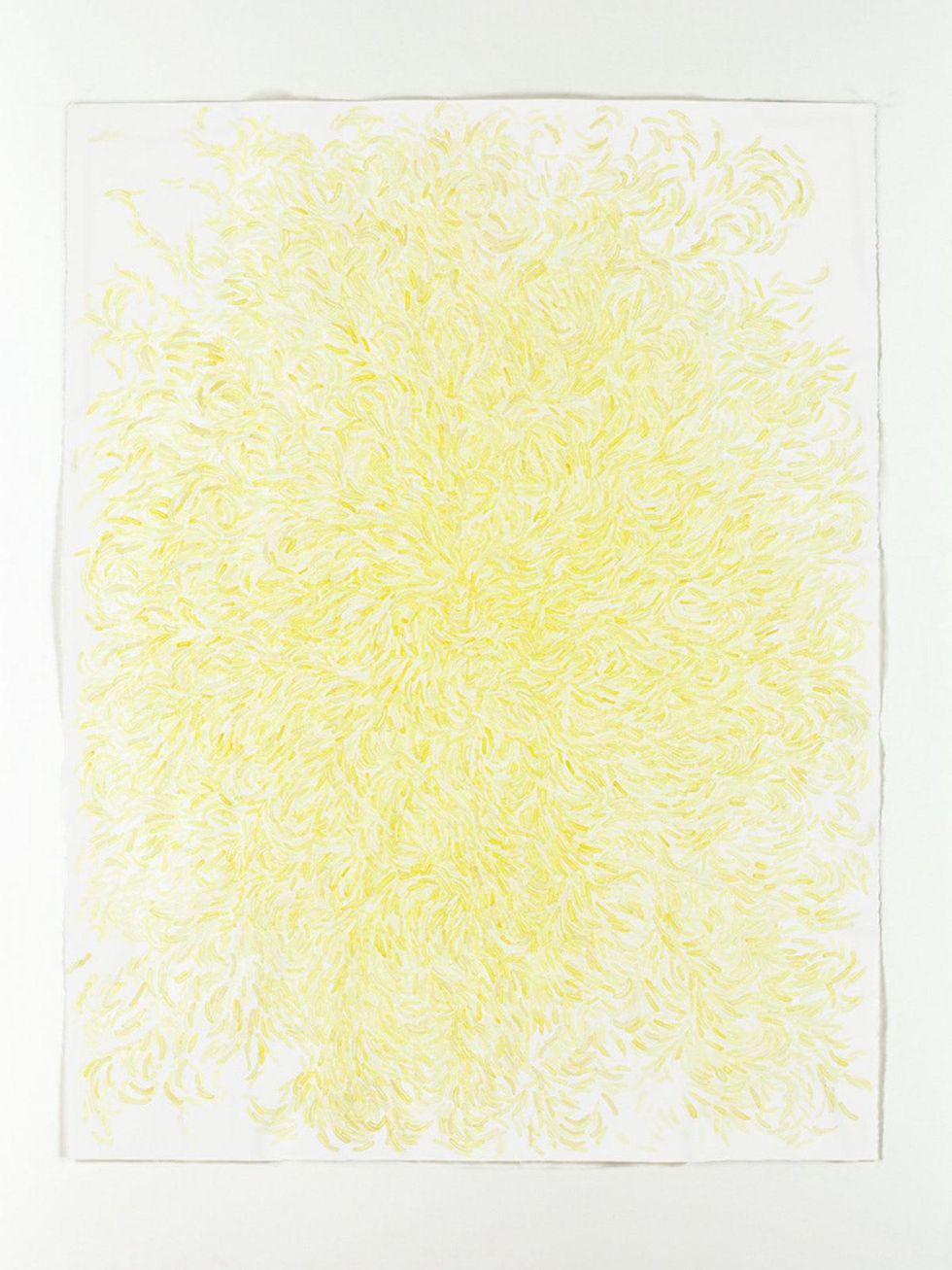

Fox worked the puppet theater for about 10 years, where he focused on themes related to manipulative forces and our lack of awareness about them. That theme emerged again in Combs #9, part of a larger body of work he has been making over the past five years, which examines the manipulative power of doctrine, and the ways in which we are governed by texts that we do not entirely understand. A rectangular body of words, unreadable sentences really, pushes outward from a grid.

If a speech could be transformed into a work of art, this is it. I tried to read it, but got lost in its incoherent tangle, just as it seems the artist planned.

Fox describes his process. "The works begin with a transcription of documents (usually texts from Catholic doctrine) in oil, ink and acrylic. I then cut the words and phrases from their paper grounds and reassemble the cut text into cloud-like forms or assemblages, rendering the words difficult, if not impossible, to read."

A rectangular body of words, unreadable sentences really, pushes outward from a grid.

"This piece reminds me of growing up reciting prayers that I didn't understand," I told Fox. He replied, "That is very much in keeping with my intention in this work. Like you, I grew up not questioning the concepts of various Catholic doctrines and dogmas."

Fox sees the concept of manipulation as an extension of his work in puppet theater. "I'm interested in trying to understand what they actually say, while also using them to create formal sculptural elements that operate in space as a presence that carries no clear meaning," he adds.

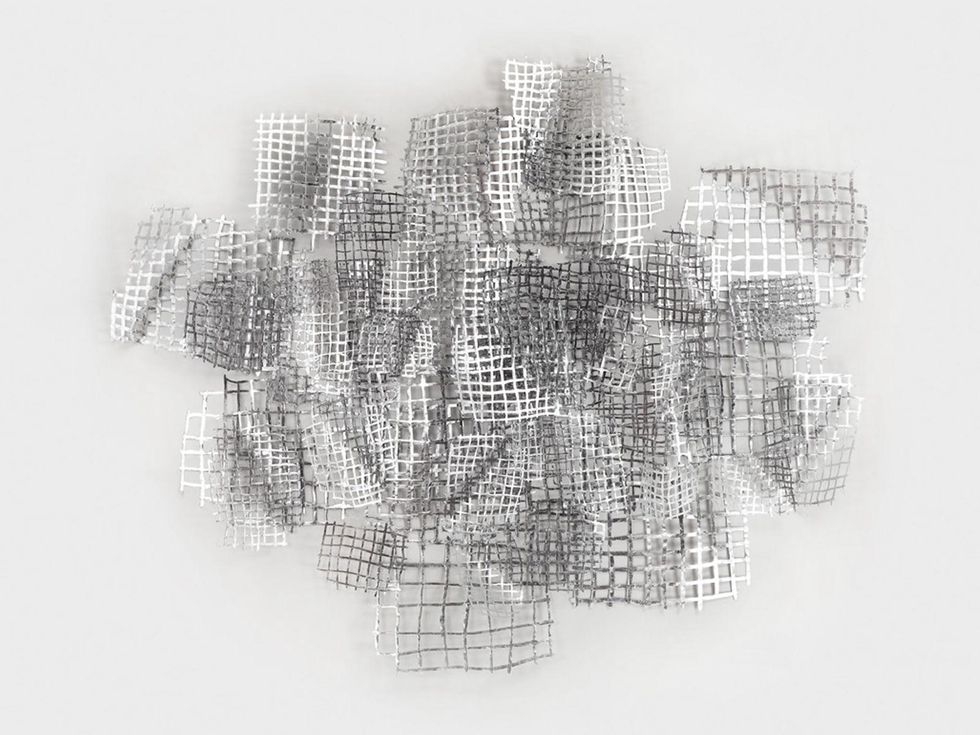

From words, Fox turned to literature in Hymn to Jane Jacobs, inspired by her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Again, the grid appears, this time crafted from aluminum leaf and ink on paper with metal pins.

"I first heard the story about Robert Moses' disastrous plan to to build a superhighway right through the middle of Washington Square Park and Greenwich Village in Manhattan, and how Jane Jacobs put a stop to it through her grass roots efforts. This led me to read her book, in which the activist and writer argues that urban renewal efforts did not take into account the actual city dwellers."

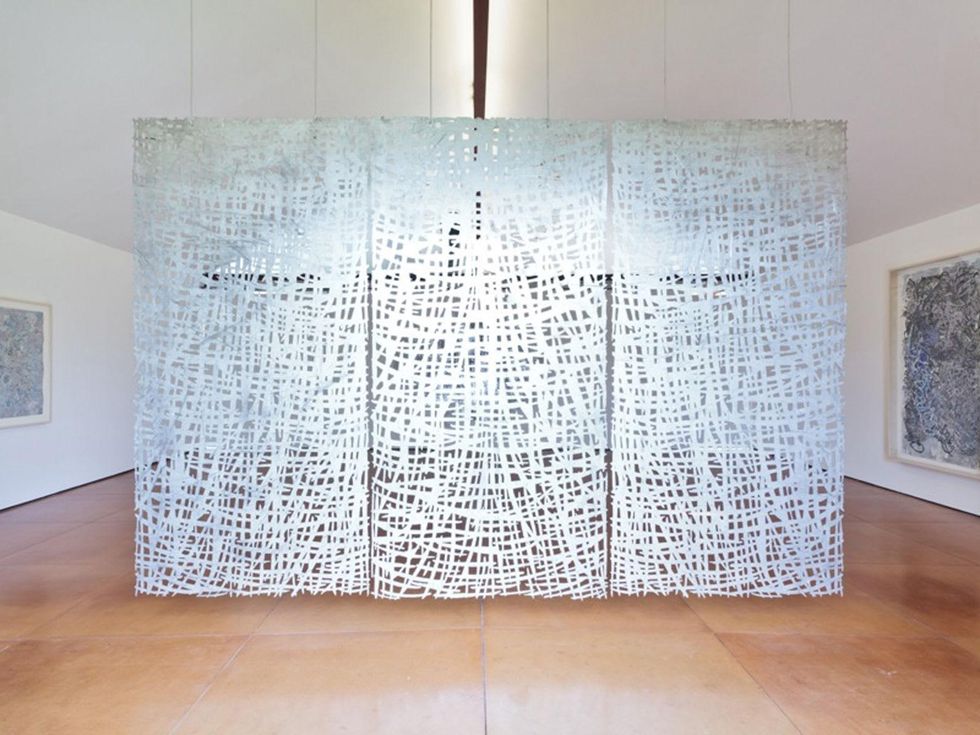

Fox's stainless steel sculpture, Triptych, also evoked the theater and immediately invited participation. I found myself standing in various locations near it, as if to enter its spell or become the "performer." Fox sees the piece formally and in its potential as something more theatrical.

"Each sculpture has approximately half negative and half positive space, which creates various optical effects. But, of course, a companion is needed — the viewer — whose eye composes a single plane from the disparate fields — the reflection of the background, the space on the other side of the mirror and the reflective surface of the steel."

"I want an opera performed in front of it," I tell the artist. "I have always wanted to do a dance piece using these steel works," quips Fox. "But I would gladly take an opera."