Something to work into your week

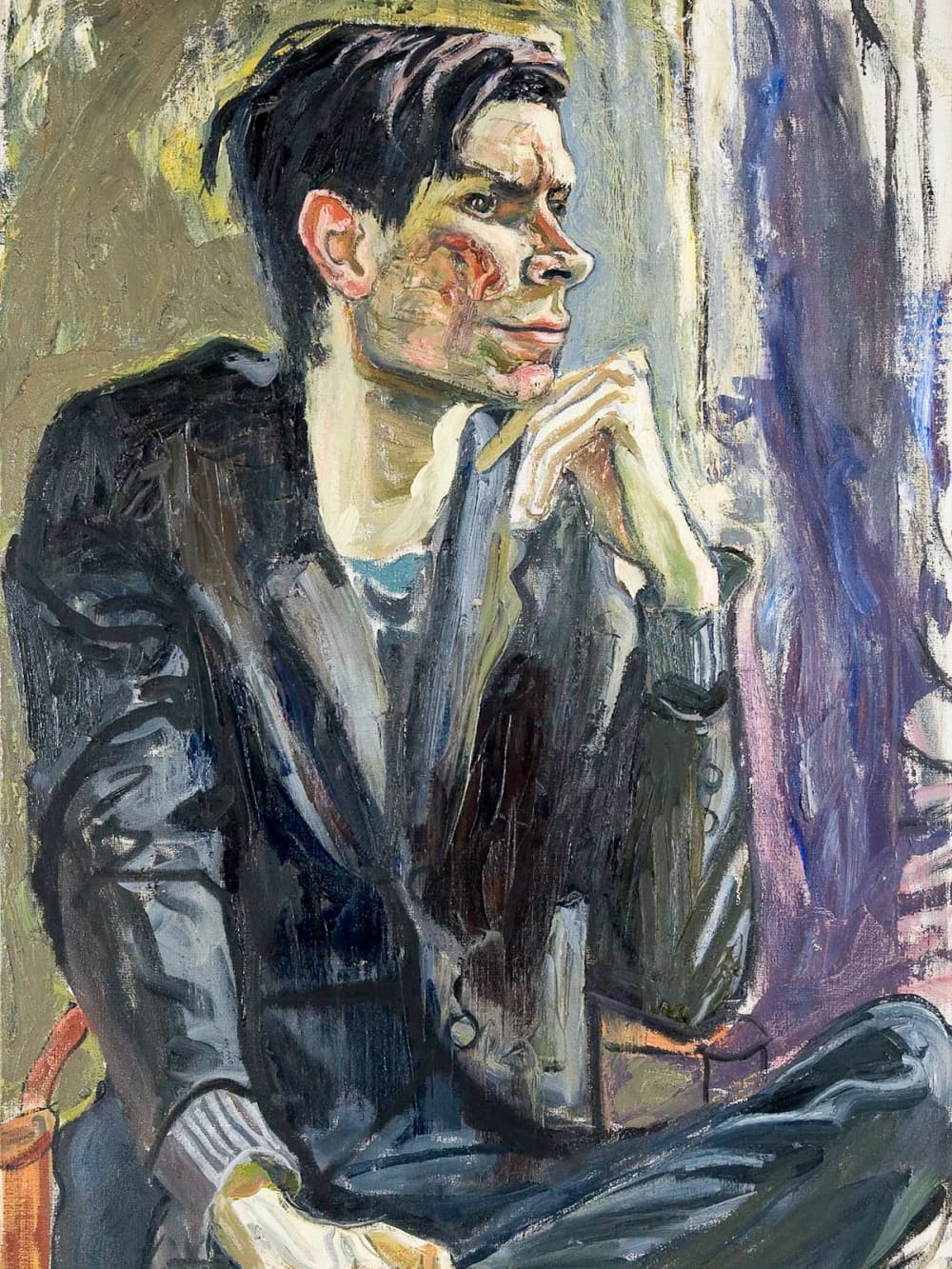

Peeling back Alice Neel: Five reasons you can't miss this great American painter

"Degenerate Madonna"

"Degenerate Madonna" "José"

"José" "Robert Smithson" (detail)

"Robert Smithson" (detail) "Audrey McMahon"

"Audrey McMahon" "Hartley"

"Hartley"

If Susan Sarandon plays you in a film — even if it's a bit part — chances are you've made it. But portraitist Alice Neel isn't a household name, and not even Netflix has that film, Joe Gould's Secret, available.

Yet Neel is touted as one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston's Alice Neel: Painted Truths, which runs through June 13th, shows us exactly why these odd and unsettling portraits matter. Here are five reasons not to miss this world premiere show, which affords the rare chance to see these works together.

1. Neel was an artist of her moment. As such, wander through a little who's who of the Great Depression, including artists supported by the WPA (Works Progress Administration). You'll find a stirring portrait of union organizer "Pat Whalen" in a moment of weary determination. There's also a fantastical image of now unheard-of poet "Kenneth Fearing" with a lively New York nightscape in the background and the fruits of his imagination dancing on the table in front of him.

Don't miss Neel's revenge on former boss "Audrey McMahon," who had the unenviable task of running the New York division of the WPA. When Neel painted McMahon from memory the result was pinched and gothic — like a dehydrated Maggie Smith. Maybe it was supervising artists that did her in.

2. Nude, nude, nude. I don't think Neel always set out to shock her readers. But when she works with nude models, as she often did, there is a fascinating grotesquerie about the body. She particularly likes tall, odd, and pregnant bodies. Why? They provide more material — literally — to expose what's hidden behind a made-up face or well-chosen outfit. Of course some of her early works did throw down the gauntlet.

No doubt she had in mind prudish art schools that often kept women out of classes with live, nude models. You can't help but notice "Bronx Bacchus" with its disaffected couple: She's bored and he's smoking while eating grapes. There's no mistaking how aggressively nude they are and also how New York they are.

They were probably just complaining about the traffic. Or the heat. Or the taxis. Or any place other than New York.

3. Family Affairs. The world of Alice Neel is full of parents and lovers, children and friends. For the most part, these portraits prefer intensity to sentiment.

The portrait of José Negron, "José," depicts musician, nightclub singer, former lover and father of Neel's son in front of a field of fiery orange. He stares out with his hands crossed on his chest. Is he dead or about to be reborn?

Neel didn't shy away from even destructive passion nor did she shy away from death or dying. When depicting Negron's brother wasting away in "T.B. Harlem" or her own mother fading away in "Last Sickness" the harsh quality of Neel's gaze is tempered with compassion. There's an almost cold perfection in depictions of her own children, such as the daughter she rarely saw, "Isabetta," or her son "Hartley" whose iconic portrait stares out with a gaze you can't miss.

Speaking of family affairs, grandson Andrew Neel directed a documentary about his grandmother. Released in 2007, Alice Neel screens Sundays at 5 p.m. in May (the 9th, 16th, 23rd, and 30th).

4. Famous Friends: It seems Alice Neel knew everyone. She appeared in her own documentary, naturally, but she also played a bishop's mother in Allen Ginsburg's 1959 Pull My Daisy. Even better, she painted countless art critics (often in states of undress), Frank O'Hara, Robert Smithson, and Andy Warhol.

The Smithson portrait depict's the creator of "Spiral Jetty" in his own swirl of dark intensity while the Warhol catches the prince of Pop Art as he vulnerably exposes the scars from his 1968 shooting. Even more captivating are Warhol's transgender stars, "Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd" who manage to be defiant and demure all at once.

5. Alice Neel: allegory or cartoon? Lately it seems cartoons are the most honest form of television. And I think anyone who grew up on cartoons of any kind might wonder if Alice Neel wasn't somehow ahead of us all in this. Her images aren't caricatures, precisely, but even the late works seem more allegorical than realistic.

Perhaps this is related to Neel's early exposure to Cuban avant-garde art, but "Degenerate Madonna" manages to be threatening, sweet, dirty, and compassionate all at once.

Not bad for someone fired repeatedly by the WPA.