The Review Is In

A well-deserved standing O: Houston Ballet's Rite of Spring is a fresh, unforgettable spectacle

You might be thinking that the most re-made ballet in dance history is The Nutcracker. At my last count, however, I had evidence that The Rite of Spring is coming in a close second.

Since the premiere 100 years ago by Vaslav Nijinsky, Igor Stravinsky, Nicholas Roerich and Sergei Diaghilev, the ballet has been interpreted by more than 200 different established choreographers.

These versions could be loosely grouped into a few major categories. There are the “tribal” versions, the ones centering on gender (only men or only women, or men and women in opposition), the solos (a significant number), the new narratives (some of them delightfully outlandish), and what I’ll call the post-modern “fragments” (many of them my favorites). I consider Paul Taylor’s and Pina Bausch’s interpretations masterpieces; both have given rise to entire threads of re-interpretation.

Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch has done a remarkable job, as evidenced at the premiere.

With this in mind, it is courageous then even to consider making a new Rite, especially in celebration of the ballet’s centennial. The odd thing is that most big ballet companies don’t have a decent version in their repertory, even though audiences are always eager to see a choreographer take it on.

Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch has done a remarkable job, as evidenced at the premiere last night at The Wortham Center. His Rite isn’t iconoclastic, which is strangely refreshing.

It doesn’t make you want to start a riot. Rather, it brings an exceedingly fresh eye to Stravinsky’s dense and polyrhythmic score, and engages the entire company in an unforgettable spectacle. It is likely his finest work of the past few years.

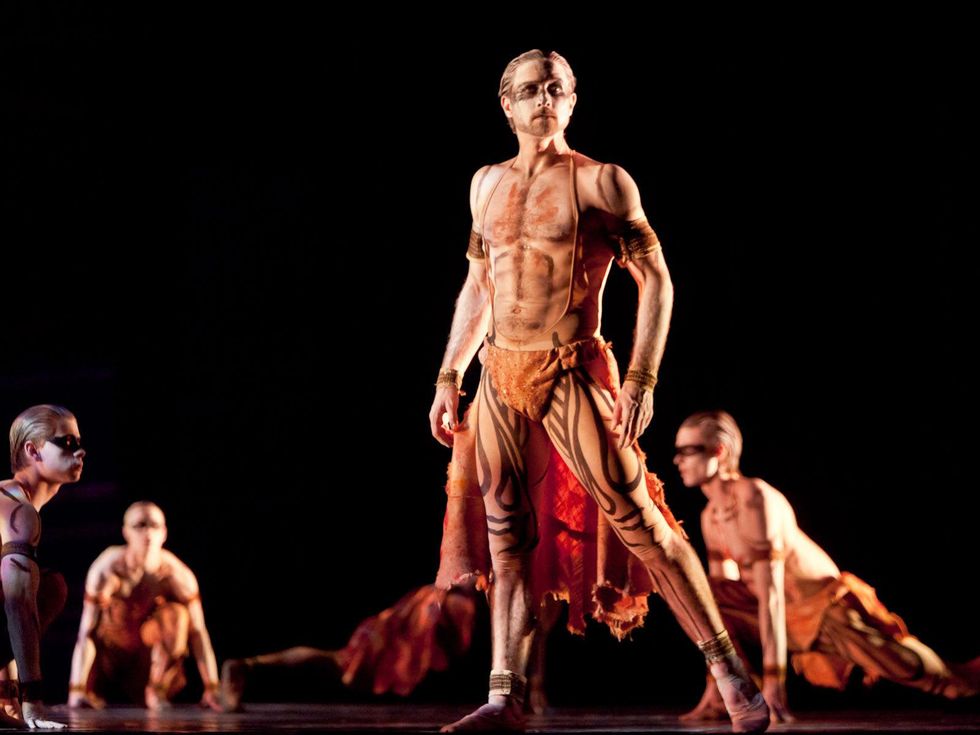

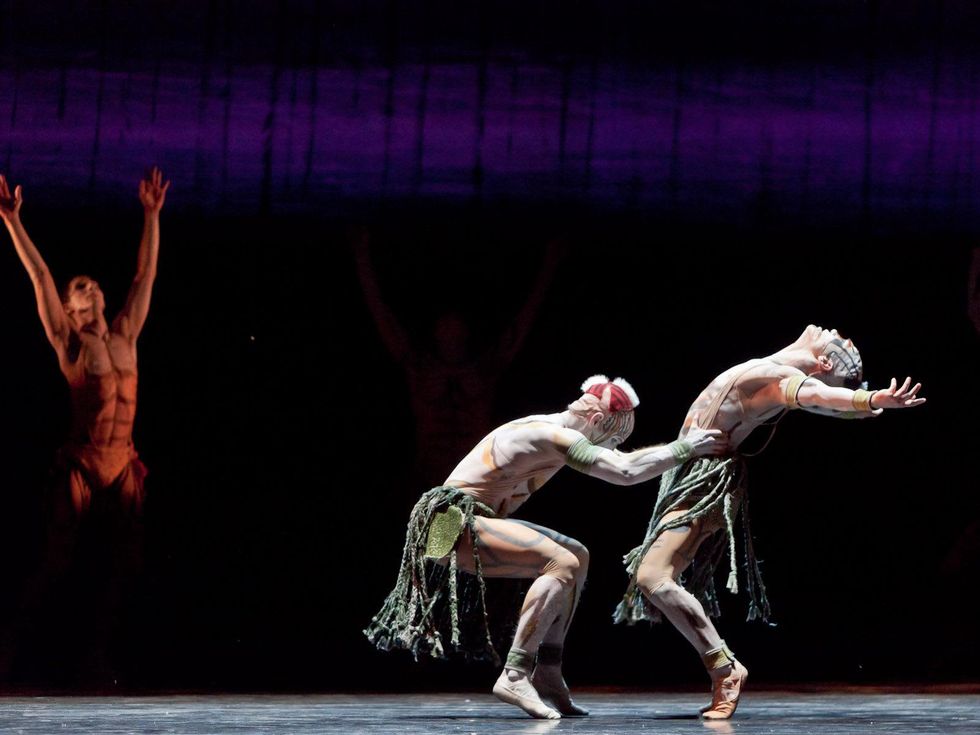

The choreography does not look particularly balletic, at least in a classical sense, and it appears that Welch was striving for something more archetypal and primitive. He has succeeded. Often, the dancing looks more like what average people do when they gather in groups. There is lots of pounding the earth and jumping towards the sky, and it works.

Welch has studied the score phrase by phrase, and some viewers might find his final decisions too musically literal. I see the overall result more as an exercise in mass and volume, which demands synchronicity rather than counterpoint. Partnering is kept to a minimum. The only moments where Welch floundered were the trembling hands put to a series of lengthy trills from the woodwind section. Those need to go, and soon.

Ermanno Florio lead the Houston Ballet Orchestra in an expert and inspired realization of Stravinsky’s rousing score.

Rosella Namok’s set designs bring sophistication and color. Welch designed his own costumes, which are too busy against Namok’s backdrops, though his color scheme and the extensive body makeup works well. Welch should probably have left the costumes to an experienced designer. Sometimes the whole thing looked a little too Aztec to me, like the cover of an Yma Sumac record from the 1950s.

The dreadlock wigs are possibly an expensive and unnecessary extravagance. In its present state, the ballet is a little overdressed.

It doesn’t make you want to start a riot. Rather, it brings an exceedingly fresh eye to Stravinsky’s dense and polyrhythmic score.

Welch’s Rite should travel well, meaning that it is a version other ballet companies with at least 50 dancers will want to perform. The audience hesitated a bit at the curtain last night, possibly because the ending is so surprising and abrupt, but then rose to a well-deserved and enthusiastic standing ovation.

The Houston Ballet premiere of Mark Morris’ 1995 Pacific, set to Lou Harrison’s murky and modal Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano, opened the program on an elegant note. It must be said that many of the greatest ballets by an American choreographer of the past 20 years have come from Morris. Pacific is danced in Martin Pakledinaz’s flowing skirts (for both men and women) and alternates inspired unison phrases with inventive ensembles and duets. It’s a perfect addition to Houston Ballet’s growing collection of Morris ballets.

The world premiere of Edwaard Liang’s Murmuration to Ezio Bosso’s Violin Concerto No. 1, Esoconcerto was a little lost in between these two works, though it has some enchanting moments. Apparently it is inspired by the patterns of birds flocking (in particular, Starlings). The choreographer, however, seems to have had a problem distinguishing foreground from background.

Without strong central images, this makes for a kind of visual exhaustion by the conclusions. Or was it the dark costumes against the dark curtain?